Table of Contents

In Robert Greene’s book, The 50th Law, he presents us with a story. This tale about the Greek philosopher Socrates gives us a little glimpse into what it means to be wise and, perhaps more importantly, what it means to be fooled by the illusion of knowledge which, counterintuitively, is also part of being wise.

Here is the story:

One day it came to the attention of the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates that the oracle at Delphi had pronounced him the wisest man in the world. This baffled the philosopher — he did not think himself worthy of such a decree. It made him uncomfortable.

He decided to simply go around Athens and find a person who was wiser than he — that should be easy and it would disprove the oracle. He engaged in many discussions with politicians, poets, craftsmen, and fellow philosophers.

He began to realize that the oracle was right. All the people he talked to had such a certainty about things, venturing solid opinions about matters of which they had no experience; they were full of so much air. If you questioned them at all, they could not really defend their opinions, which seemed based on something they had decided years earlier.

His superiority, he realized, was that he knew that he knew nothing. This left his mind open to experiencing things as they are, the source of all knowledge.

How to Think vs. What to Think

Simply put, wisdom can only exist in a mind that has first learned how to think.

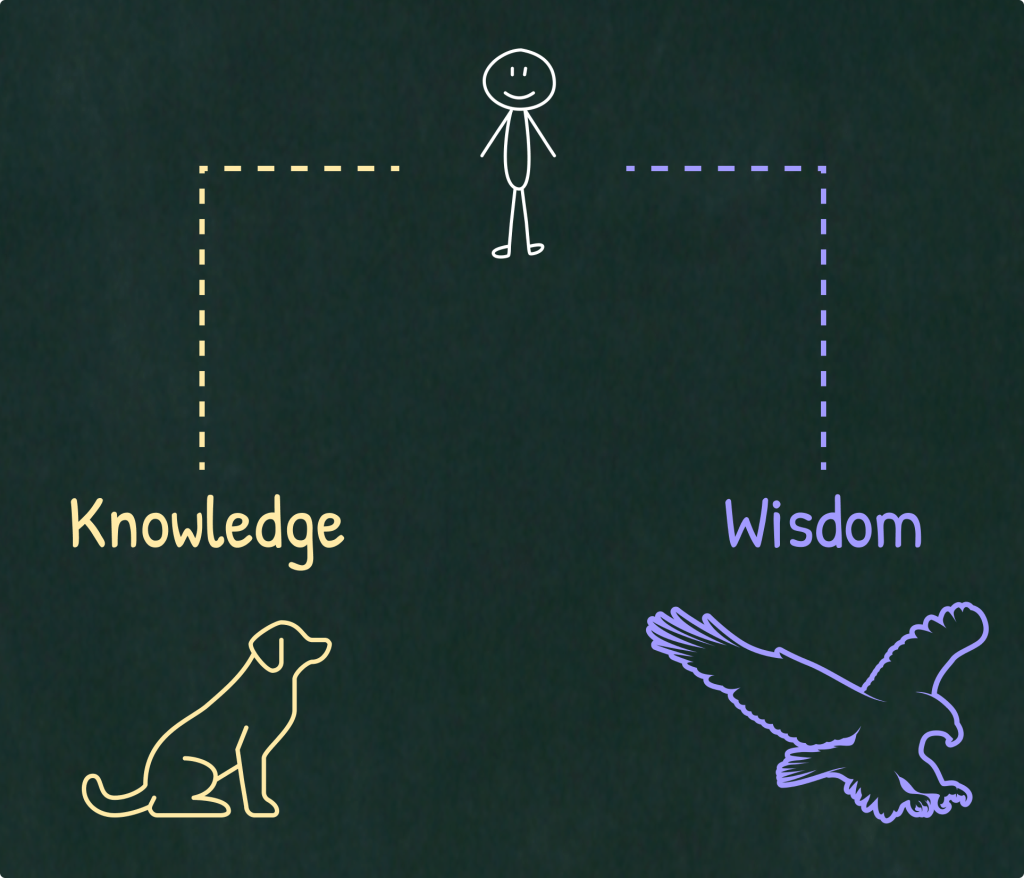

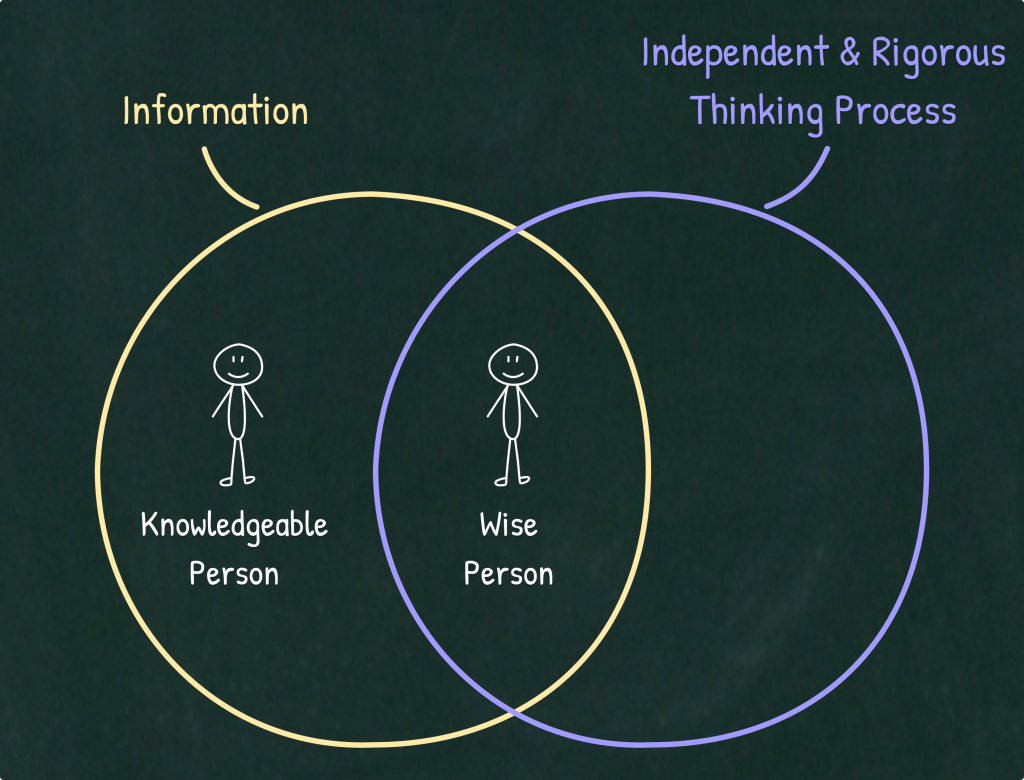

So, the fundamental difference between knowledge and wisdom resides not so much on the information acquired, but on how the information was acquired.

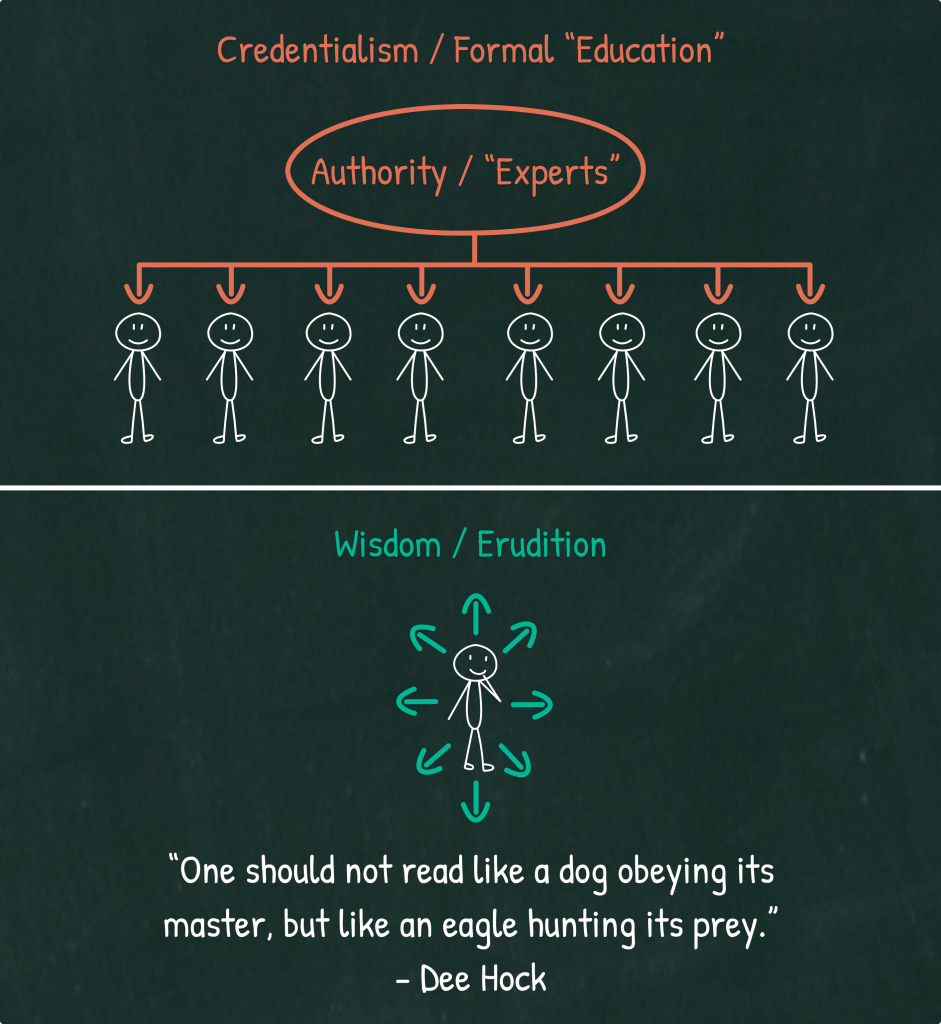

When you acquire information from a place of child-like curiosity and skepticism, and you reason through it independently and thoroughly, you set yourself up to become wiser. Whereas if you only memorize things or acquire knowledge for some external incentive — such as a desire to appear clever, to pass a test, or to get a credential — then you might become more knowledgable, but you won’t become wiser. And if you want to develop real skills and a worldview that is congruent with reality, what you truly want is wisdom, not just raw information and data.

One reason this happens is because, to a certain degree, we’re all susceptible to authority bias. The average person tends to accept what those in a position of authority or an “expert” tells them to believe, especially in areas where they don’t feel competent to make their own decisions. This happens even when what they’re being told doesn’t align with their own lived experiences. Thus if they’re not confident in what they believe, if they’re in financial debt to those demanding their compliance, or if they’re not confident in their ability to decide what’s best for them at the risk of being ostracized, they’ll usually go along to get along.

In his book, The Elon Musk Blog Series, Tim Urban captured how this authority bias works against individuals and groups who ran counter to the status quo:

The flood geologists of the 17th and 18th centuries weren’t stupid. And they weren’t anti-science. Many of them were just as accomplished in their fields as their science geologist colleagues. But they were victims — victims of a religious dogma they were told to believe without question. The recipe they followed was scripture, a recipe that turned out to be wrong. And as a result, they proceeded on their path with a fatal flaw in their thinking — a software bug that told them that one of the undeniable first principles when thinking about the Earth was that it began 6,000 years ago and that there had been a flood of the most epic proportions. With that “software bug” in place, all further computations were moot. Any reasoning tree that puzzled upwards with those assumptions at its root had no chance of finding truth. Even more than being victims of any dogma, the flood geologists were victims of their own certainty.

Without certainty, dogma has no power.

And when data is required in order to believe something, false dogma has no legs to stand on. It wasn’t the church dogma that hindered the flood geologists, it was the church mentality of faith-based certainty. That’s what Stephen Hawking meant when he said, “The greatest enemy of knowledge is not ignorance, it is the illusion of knowledge.” Neither the science geologist nor the flood geologist started off with knowledge.

But what gave the science geologist the power to seek out the truth was knowing that he lacked knowledge. The science geologists subscribed to the lab mentality, which starts by saying “I don’t know shit” and works upwards from there. If you want to see the lab mentality at work, just search for famous quotes of any prominent scientist and you’ll see each one of them expressing the fact that they don’t know shit.

Here’s Isaac Newton: To myself I am only a child playing on the beach, while vast oceans of truth lie undiscovered before me.

And Richard Feynman: I was born not knowing and have had only a little time to change that here and there.

And Niels Bohr: Every sentence I utter must be understood not as an affirmation, but as a question.

[Elon] Musk has said his own version: You should take the approach that you’re wrong. Your goal is to be less wrong.

The reason these outrageously smart people are so humble about what they know is that as scientists, they’re aware that unjustified certainty is the bane of understanding and the death of effective reasoning. They firmly believe that reasoning of all kinds should take place in a lab, not a church.

The “Shut Off” Mechanism

Proper education is one long exercise in the augmentation of high cognition so that our wisdom becomes strong enough to destroy wrong thinking maintained by resistance to change.

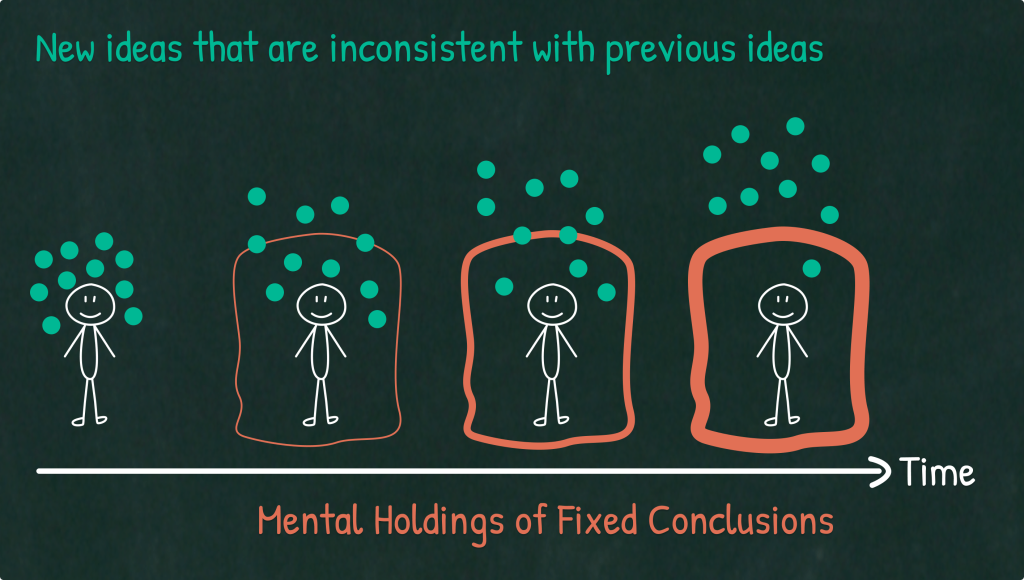

As Lord Keynes pointed out about his exalted intellectual group at one of the greatest universities in the world, it was not the intrinsic difficulty of new ideas that prevented their acceptance. Instead, the new ideas were not accepted because they were inconsistent with old ideas in place. What Keynes was reporting is that the human mind works a lot like the human egg. When one sperm gets into a human egg, there’s an automatic shut-off device that bars any other sperm from getting in. The human mind tends strongly toward the same sort of result. And so, people tend to accumulate large mental holdings of fixed conclusions and attitudes that are not often reexamined or changed, even though there is plenty of good evidence that they are wrong.

– Charlie Munger (Ex-Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway)

[From the book: Poor Charlie’s Almanack]

So, we tend to accept ideas from authorities without deeply questioning them, and then we make the problem worse by holding onto those ideas like our life depends on them. Seen in this light, it sounds crazy! But that’s very much what’s going on in the world.

The Life Edge of Wisdom

If you start from a place of curiosity and skepticism (but with optimism that you have the capacity to discover the truth), you’ll begin to automatically boil things down to its root. And when doing that, your understanding of those issues will be more robust.

Then, when you find new evidence that contradicts what you think you know, the next step is to be willing to upgrade your ideas and remove your old preconceptions. In this way your worldview always gets closer and closer to the real world and comports to your lived experiences.

Fair warning: This multi-step approach will take you more time and effort (compared to meekly adopting the arguments of an authoritative figure), however, in the long run it will equip you with actual wisdom. And this will give you an edge in life for a few reasons:

1. For most people, the price of thorough and independent reasoning is higher than their perception of the benefit.

The reason for this is that we have a bias to overvalue things in the short-term (in this case, we overvalue the time and effort required for understanding), and undervalue them in the long-term (in this case, we undervalue the benefit of gaining a solid understanding on a specific topic — which can be useful for the rest of our lives).

Most people would rather die than think, and many of them do!

– Bertrand Russell

2. As we have seen, most people are susceptible to authority bias and, likely due to how they were educated, are more prone to being told what to think instead of being taught how to think.

In fact, in his book The Beginning of Infinity, the renowned physicist David Deutsch attributes the rejection of authorities as one of the three key ingredients that originated the Renaissance movement (the other two are: the scientific method, and the quest for good and non-easily variable explanations). Isn’t it ironic that now the “institutions of knowledge” are, to some extent, religiously dogmatic in their thinking? This is particularly egregious when you look at energy policy, especially nuclear power and climate change.

Thus, the tragic outcome is that most people will just memorize things with the aim of passing tests. They see knowledge as a dull commodity, worth only as much as the prestige of the credential which it can potentially unlock.

Academia is to knowledge what prostitution is to love; close enough on the surface but, to the nonsucker, not exactly the same thing.

– Nassim Taleb (Author, Former Options Trader, and Risk Analyst)

[From his book: The Bed Of Procrustes]

Charlie Munger claims this is a “perfectly disastrous way to think and a perfectly disastrous way to operate in the world.” Here’s the full passage from his book, Poor Charlie’s Almanack:

What is elementary, worldly wisdom? Well, the first rule is that you can’t really know anything if you just remember isolated facts and try and bang ’em back. If the facts don’t hang together on a latticework of theory, you don’t have them in a usable form.

You’ve got to have models in your head. And you’ve got to array your experience — both vicarious and direct — on this latticework of models. You may have noticed students who just try to remember and pound back what is remembered. Well, they fail in school and fail in life. You’ve got to hang experience on a latticework of models in your head.

What are the models? Well, the first rule is that you’ve got to have multiple models — because if you have just one or two that you’re using, the nature of human psychology is such that you’ll torture reality so that it fits your models, or at least you’ll think it does. You become the equivalent of a chiropractor, who, of course, is the great boob in medicine. It’s like the old saying, “To the man with only a hammer, every problem looks like a nail.” And, of course, that’s the way the chiropractor goes about practicing medicine. But that’s a perfectly disastrous way to think and a perfectly disastrous way to operate in the world. So you’ve got to have multiple models.

And the models have to come from multiple disciplines — because all the wisdom of the world is not to be found in one little academic department. That’s why poetry professors, by and large, are so unwise in a worldly sense. They don’t have enough models in their heads. So you’ve got to have models across a fair array of disciplines.

You may say, “My god, this is already getting way too tough.” But fortunately, it isn’t that tough — because 80 or 90 important models will carry about 90 percent of the freight in making you a worldly-wise person. And, of those, only a mere handful really carry very heavy freight.

Naval Ravikant also shared an insightful thought in a conversation with Joe Rogan:

Now what I realize is that the biggest mistake was memorization — because when you’re actually trying to live your life in congruence with reality you want to have a deep understanding of what you do and why you do it… and so it’s much more important to know the basics really well than it is to know the advanced.

Knowing calculus wouldn’t help you today… it doesn’t help you in business, doesn’t help you in most things… but knowing arithmetic will help you really — whether it’s at the corner grocery store counting change, to figuring out the value of your podcast business, to figuring out how to do the probability math on some action that you want to take.

So, understanding basic mathematics cold is way more important than memorizing calculus concepts. And this is true of, I think, all reasoning — it’s much better to know the basics from the ground up (a solid foundation of understanding, a steel frame of understanding) than it is to just have a scaffolding where you are just memorizing advanced concepts.

This is why there are a lot of people (I’m sure that you listen to) who are really smart, they use a lot of jargon and you can’t quite follow their reasoning… you don’t know how they’re putting things together and you have this deep down suspicion that they don’t even really understand.

So, if you look at the most powerful thinkers — especially the ones where money or life is on the line — they have to understand the basics really, really well…

Richard Feynman, the physicist, had this piece in one of his lectures where he takes you from counting numbers on your hand all the way to calculus in four pages of text (orally, but written down is four pages of text) and it’s a complete unbroken logical chain that takes you through geometry, trigonometry, precalculus, analytic geometry, graphs, everything… all the way to calculus. He understood numbers at a core level, he didn’t have to memorize anything!

When you’re memorizing it’s an indication that you don’t understand, you should be able to re-derive anything on the spot and if you can’t you don’t know it.

Formal Knowledge vs. Real Skills

From the previous chapter, let’s assume the primary purpose of getting credentialed by a college or university is to either (a) get a job or (b) to elevate your status and thus, hopefully, your earning power. Many employers focus on credentials as a proxy for formal knowledge because it’s become the fastest and easiest legal way to filter job candidates. But the credentials (or formal knowledge) are not the real thing; the real thing is to actually have the skills.

Ask yourself: What are most organizations hiring for when they post a job? Skills, not credentials or DEI quotas.

Yet credentialism has become the proxy for skills in many fields. And thus, most organizations focus on that proxy because it’s easier, in the case of credentials, and ideologically convenient, in the case of DEI hires, to eschew skills-based hiring.

Universities, particularly in the U.S., are in on this as well: They are quite happy to sell their brand to the highest bidder, as the exploding cost of higher education has demonstrated, or to the bidder who comports with their ideology, as Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard demonstrated, because universities benefit from organizations demanding their credentials. It’s a seller’s market, after all, if you’re an elite university. As Scott Galloway said, Harvard is “no longer in higher education. They’re a hedge fund offering classes.”

By the way, this habit of focusing on proxies instead of the real thing happens in many other areas. In the book Invent and Wander, Jeff Bezos gives some great examples:

As companies get larger and more complex, there’s a tendency to manage to proxies. This comes in many shapes and sizes, and it’s dangerous, subtle, and very Day 2.

[Day 2 is stasis. Followed by irrelevance. Followed by excruciating, painful decline. Followed by death.]

A common example is process as proxy. Good process serves you so you can serve customers. But if you’re not watchful, the process can become the thing. This can happen very easily in large organizations. The process becomes the proxy for the result you want. You stop looking at outcomes and just make sure you’re doing the process right. Gulp. It’s not that rare to hear a junior leader defend a bad outcome with something like, “Well, we followed the process.” A more experienced leader will use it as an opportunity to investigate and improve the process. The process is not the thing. It’s always worth asking, do we own the process or does the process own us? In a Day 2 company, you might find it’s the second.

Another example: market research and customer surveys can become proxies for customers.

Naval Ravikant pointed out that the really smart people wouldn’t even ask a question such as, “What is your credential?” to evaluate someone’s level of ability in order to discern who are the experts and who are the imitators. In a fireside chat with Niklas Anzinger, he said:

Smart people (capable people) don’t let themselves be pigeonholed into one definition… that is a disease of credentialism because we created this University and now you gotta go to university, and you gotta get a degree in something, then people say: “Well, what is your expertise? What is your credential?”

That’s a question dumb people ask. Smart people don’t ask that. Smart people don’t need to know your credentials, they just talk to you for 5 minutes and they figure out if you know what you’re talking about or not.

And a really good person (a so-called natural philosopher) can be good in any branch of anything. Nature has no boundaries! Nature has no concept of mathematics versus physics versus chemistry… It is all one thing.

How Real Skills Attract Success

Over the long run, having real knowledge and skills is the surest way to succeed in the marketplace. Especially if you are a freelancer (where you are fully accountable for the outcome) or you’re working on a startup (where it is easy to evaluate your contribution to the business outcomes). So, the more direct the link between your “input” (your time, effort and expertise) and the output (e.g., business profits), the more it matters that you actually have real skills.

Paul Graham is the founder of YC, a Venture Capital firm that has invested in over 5,000 startups since 2005 [Source]. In his book, Hackers and Painters, he said:

When the things you do have real effects, it’s no longer enough just to be pleasing. It starts to be important to get the right answers, and that’s where nerds show to advantage.

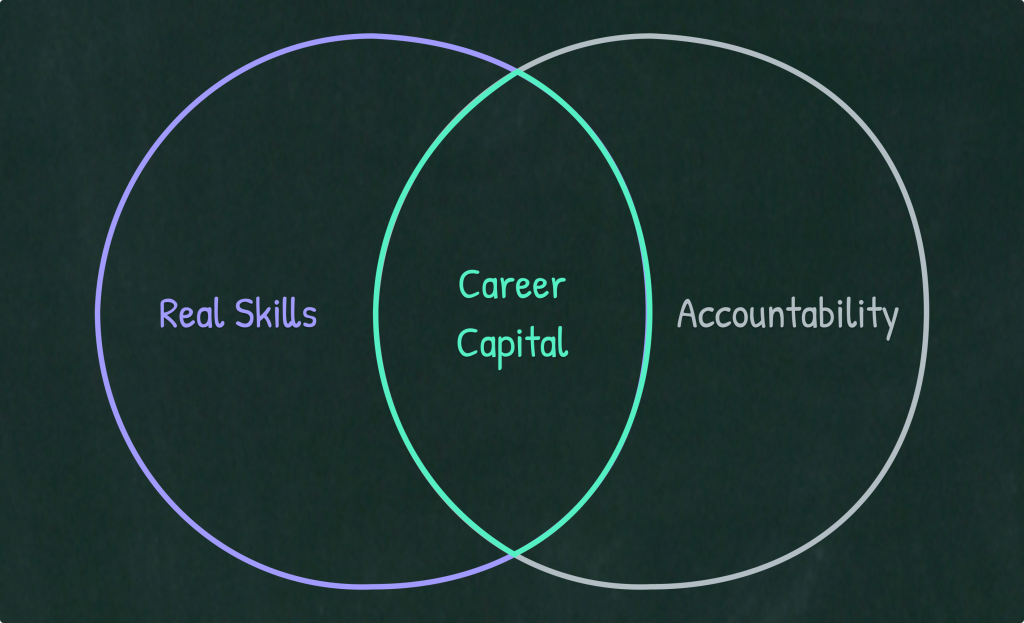

And by the way, this is the best path anyways. Because if you have the skills and you are accountable for the outcome, you are much less replaceable within a company. And that translates into what Cal Newport calls “career capital,” which gives you the power to negotiate better terms for yourself — such as more income, autonomy, and flexibility.

This is the reason why most “digital nomads” (who can actually sustain the nomadic lifestyle without having to partially fund it with their savings) are either serial entrepreneurs, independent finance professionals, or top-tier programmers [Source]. These individuals share in common the possession of real skills, validated by the market (in the case of the entrepreneurs), or by clients who track them on the quality of their work (in the case of the freelancers).

As Jim Rohn famously put it, “You can have more than you’ve got, because you can become more than you are.” [Source]

And Naval Ravikant put it this way, “The most important skill for getting rich is becoming a perpetual learner.” [from his book: The Almanack of Naval Ravikant]

Key Takeaways – How To Go From Knowledge To Wisdom (and Real Skills)

1. The first thing is to develop the habit of independent and critical thinking against all ideas. So that you develop a solid frame of understanding that is congruent with reality.

2. The next thing is to remember that we, as humans, have a natural tendency to be protective of our ideas. This is a disadvantage. If our goal is to develop a worldview that is as close as possible to the real world, then we can mitigate this tendency by developing a willingness to search for contradictory evidence and re-adjust our ideas as much as necessary.

Any year that passes in which you don’t destroy one of your best-loved ideas is a wasted year.

– Charlie Munger

[Source]

3. If you apply this thinking process to your career, you will be able to develop real skills and become much more valuable in the marketplace — which translates into more income, autonomy, and flexibility.

If You Liked This Essay, Check Out These Sources

- The 50th Law, by Robert Greene.

- “Knowledge vs. True Opinion: How To Determine if What You Believe Is Worth Defending”, by Julio Froment.

- The Elon Musk Blog Series, by Tim Urban.

- Poor Charlie’s Almanack, by Peter Kaufman and Charlie Munger.

- The Beginning of Infinity, David Deutsch.

- “We Have Already Clean Energy“

- “Numbers Behind the Narrative: What Climate Science Actually Says”

- The Bed Of Procrustes, Nassim Nicholas Taleb.

- Naval Ravikant on the Joe Rogan Experience.

- “Blame IQ Tests for the Student Debt Problem“, by Patrick Watson.

- Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard

- How the US Is Destroying Young People’s Future | Scott Galloway | TED

- Invent and Wander, by Walter Isaacson.

- “Experts vs. Imitators”, by Shane Parrish.

- Fireside Chat with Naval Ravikant & Niklas Anzinger | AI & Technological Progress – Vitalia

- “From Full-Time to Freelance: The Ten Commandments of Contracting”

- Hackers and Painters, by Paul Graham.

- So Good They Can’t Ignore You, by Cal Newport.

- “Globetrotting Digital Nomads: The Future Of Work Or Too Good To Be True?”

- The Almanack of Naval Ravikant, by Eric Jorgenson.

Wisdom & Philosophy Quotes: The Importance of Wisdom & Philosophy

We are all seeking wisdom throughout philosophy. This is the tie that binds the community together. We all seek to use different avenues of philosophy to arrive at wisdom and…