Table of Contents

All my life I’ve been given the career advice that I have to “follow my passion.” I have to figure out what I love and then pursue a career aligned with it.

But every time I asked myself, “What’s a passion that I can make into a career?”, I never came up with a good answer. “Is there something wrong with me?” — I would frequently wonder.

It was only when I started reading about the lives of highly successful and passionate people — such as Steve Jobs, Sam Altman, Paul Graham, Peter Thiel, Ben Horowitz, and Naval Ravikant — that everything completely changed. Only then, did I see clearly what I should do.

If you’re also struggling with this issue, I invite you to read this article — where I distill the insights I learned from these people who were able to transmute their careers into one of their passions.

Did Steve Jobs Follow His Passion? The Answer May Surprise You

You might have heard Steve Jobs’ Commencement Speech at Stanford in 2005. In that speech, he said:

You’ve got to find what you love… Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do.

From his advice, you would naturally think that first you need to figure out what you love to do — your passion — and then map it to a job or a career. But if we look at the life of Steve Jobs, we can see that he did not follow this path.

Cal Newport conducted a deep research on the life of Steve Jobs, and it clearly shows that he didn’t have any pre-existing passion for what would become his life’s work — Apple. You can read his observations below, taken from his book So Good They Can’t Ignore You:

If you had met a young Steve Jobs in the years leading up to his founding of Apple Computer, you wouldn’t have pegged him as someone who was passionate about starting a technology company. Jobs had attended Reed College, a prestigious liberal arts enclave in Oregon, where he grew his hair long and took to walking barefoot. Unlike other technology visionaries of his era, Jobs wasn’t particularly interested in either business or electronics as a student. He instead studied Western history and dance, and dabbled in Eastern mysticism.

Jobs dropped out of college after his first year, but remained on campus for a while, sleeping on floors and scrounging free meals at the local Hare Krishna temple. As Jeffrey S. Young notes in his exhaustively researched 1988 biography, Steve Jobs: The Journey Is the Reward, Jobs eventually grew tired of being a pauper and, during the early 1970s, returned home to California, where he moved back in with his parents and talked himself into a nightshift job at Atari (The company had caught his attention with an ad in the San Jose Mercury News that read, “Have fun and make money.”). During this period, Jobs split his time between Atari and the All-One Farm, a country commune located north of San Francisco. At one point, he left his job at Atari for several months to make a mendicant’s spiritual journey through India, and on returning home he began to train seriously at the nearby Los Altos Zen Center.

In 1974, after Jobs’s return from India, a local engineer and entrepreneur named Alex Kamradt started a computer time-sharing company dubbed Call-in Computer. Kamradt approached Steve Wozniak to design a terminal device he could sell to clients to use for accessing his central computer. Unlike Jobs, Wozniak was a true electronics whiz who was obsessed with technology and had studied it formally at college. On the flip side, however, Wozniak couldn’t stomach business, so he allowed Jobs, a longtime friend, to handle the details of the arrangement. All was going well until the fall of 1975, when Jobs left for the season to spend time at the All-One commune. Unfortunately, he failed to tell Kamradt he was leaving. When he returned, he had been replaced.

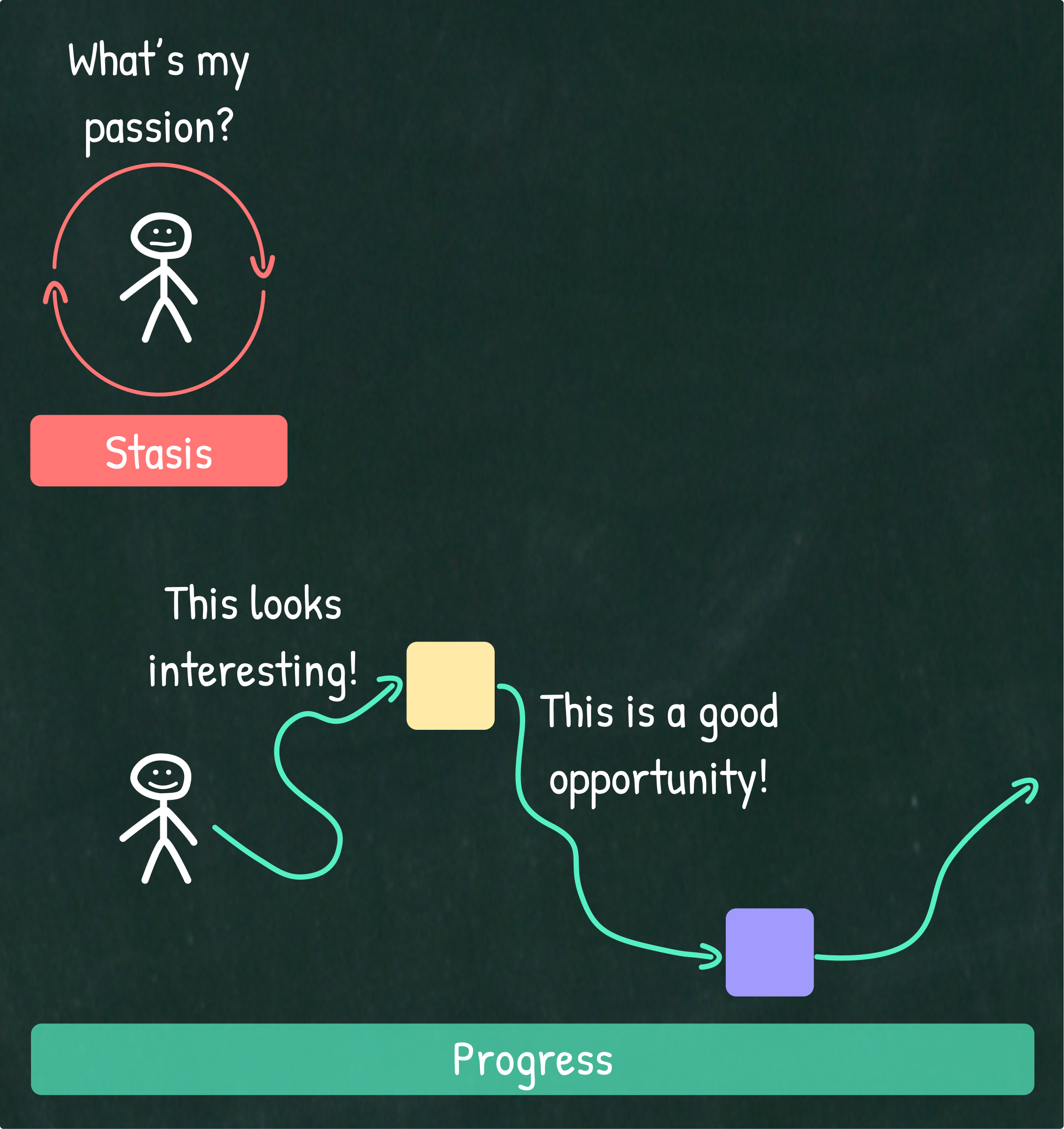

As we can see, Steve Jobs was not someone who had a clear idea of what he was passionate about. He was in seeking mode, doing things he found interesting or exploiting opportunities that came along. The birth of Apple did not stem from his passion for technology and entrepreneurship, but from his willingness to capture a business opportunity — which only later would bring him passion.

So instead of trying to figure out what your passion is in the abstract, it’s better to have an action bias — to just do things.

The way to figure out what to work on is by working. If you’re not sure what to work on, guess. But pick something and get going. You’ll probably guess wrong some of the time, but that’s fine. It’s good to know about multiple things; some of the biggest discoveries come from noticing connections between different fields.

– Paul Graham (Co-founder of YC)

[Excerpt from his essay: “How To Do Great Work”]

I have a ton of different interests, and I don’t have focus. You’ll never be sure [on what to do]. You don’t want to be sure.

– William Morris (Renowned glass blower)

[Excerpt from the book: So Good They Can’t Ignore You]

Compelling careers often have complex origins that reject the simple idea that all you have to do is follow your passion.

– Cal Newport

[Excerpt from the book: So Good They Can’t Ignore You]

Why Following Your Passion Is Bad Career Advice

Ben Horowitz, during his commencement address at Columbia University in 2015, told students not to follow their passion, and he laid out four issues with the popular advice of following your passions:

1. Passions are hard to prioritize. Are you more passionate about Math or Engineering? Are you more passionate about History or Literature? Are you more passionate about Video games or K-Pop? These are tough decisions. How do you even know?

On the other hand, what are you good at? Are you better at Math or Writing? That’s a much easier thing to figure out.

2. Passions come and go. What you are passionate about at 21 is not necessarily what you are going to be passionate about at 40. [It’s hard to predict what you’ll grow to love.]

3. You are not necessarily good at your passion — just because you love singing doesn’t mean that you should be a professional singer.

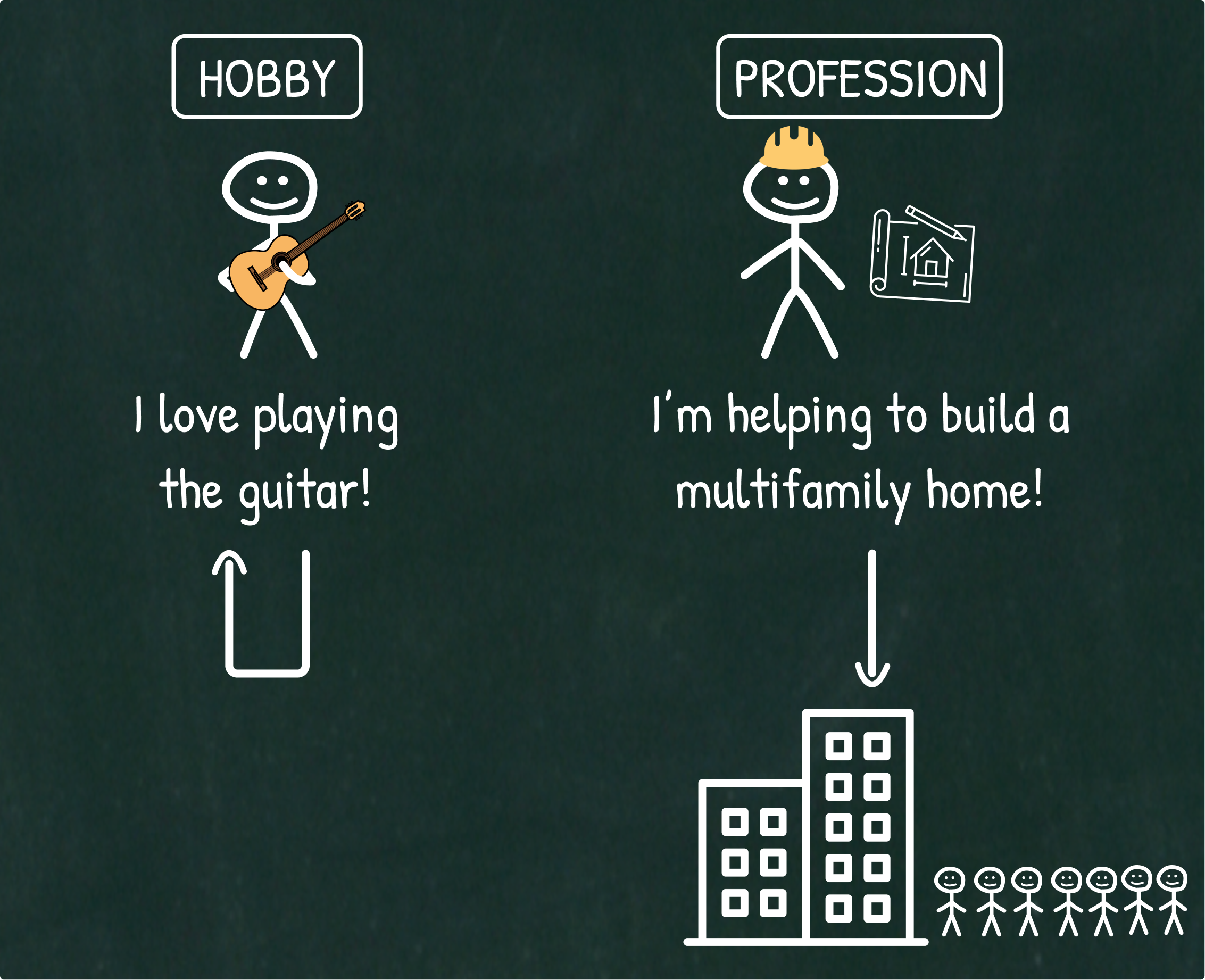

4. Finally, and most importantly, following your passion is a very “me-centered,” i.e. selfish, view of the world. And as you go through life, you’ll find the following to be true: What you take out of the world is much less important than what you put into the world.

Another important issue is that, even if you are able to make a living out of a pre-existing passion, your attitude and feelings towards that activity will change. Because when the financial incentive gets in the way, you are no longer doing the activity for its own sake. A big gaming streamer once said to the YouTuber Ali Abdaal, “I’ll do anything to not have to make a video.”

If you want to make people miserable, pay them (generously and predictably) for their hobbies.

– Nassim Nicholas Taleb (Author, Former Options Trader, and Risk Analyst)

[Source: Tweet by Nassim Taleb]

Your hobbies (avocations) are meant to be pursued for their own sake, for the sheer joy that it brings you. It’s about you, not others (or money).

On the other hand, your profession (vocation) is meant to be pursued for the sake of others, for the value that it adds to society — and in exchange for that value, you make money. It’s about others, not you.

Lastly, you might wonder: “If I’m ultimately making money from my profession, isn’t it about me?” But the thing is, it’s much better to be a mission-driven builder than it is to be a “mercenary” trying to monetize your passions and interests. As Jeff Bezos pointed out, you ironically end up making more money if you are genuinely mission-driven.

I would take a missionary over a mercenary any day. Mercenaries want to flip the company and get rich. Missionaries want to build a great product or service. And one of those great paradoxes, it’s usually the missionaries who end up making more money anyway.

– Jeff Bezos (Founder of Amazon and Blue Origin)

Understanding the Paradox of How Adopting a Craftsman Mindset Helps You Find a Career You’re Passionate About

The essence of the craftsman mindset can be fully captured by this quote from Ben Horowitz, mentioned earlier:

What you take out of the world is much less important than what you put into the world.

Someone with this mindset focuses on what he can offer the world, what value he can produce. And this is not only more important and meaningful than the passion mindset’s self-centered view, but it’s also how you can end up finding joy in what you do.

You must live for another if you wish to live for yourself.

…

The duty of a man is to be useful to his fellow-men; if possible, to be useful to many of them; failing this, to be useful to a few; failing this, to be useful to his neighbors, and, failing them, to himself: for when he helps others, advances the general interests of mankind.

– Seneca (Stoic philosopher)

[Excerpt from the book: Dialogues]

Those of whom that are like sponges that only takes without giving will only lose happiness.

– John D. Rockefeller (Founder of Standard Oil Company)

[Excerpt from the book: The 38 letters from J.D. Rockefeller to his son]

Many people think a pre-existing passion is necessary to develop the craftsman mindset. But again, if we see what actually goes on in the lives of great performers, we see that this is far from the truth. Cal Newport explained it best in his book So Good They Can’t Ignore You:

When I began exploring the craftsman mindset on my blog, some of my readers became uneasy. I noticed them starting to home in on a common counterargument, which I should address before we continue. Here’s how one reader put it:

“Tice is willing to grind out long hours with little recognition, but that’s because it’s in service to something he’s obviously passionate about and has been for a long time. He’s found that one job that’s right for him.”

I’ve heard this reaction enough times to give it a name: “the argument from pre-existing passion.” At its core is the idea that the craftsman mindset is only viable for those who already feel passionate about their work, and therefore it cannot be presented as an alternative to the passion mindset.

I don’t buy it.

First, let’s dispense with the notion that performers like Jordan Tice or Steve Martin are perfectly secure in their knowledge that they’ve found their true calling. If you spend any time with professional entertainers, especially those who are just starting out, one of the first things you notice is their insecurity concerning their livelihood. Jordan had a name for the worries about what his friends are doing with their lives and whether his accomplishments compare favorably: “the cloud of external distractions.”

Fighting this cloud is an ongoing battle. Along these lines, Steve Martin was so unsure during his decade-long dedication to improving his routine that he regularly suffered crippling anxiety attacks. The source of these performers’ craftsman mindset is not some unquestionable inner passion, but instead something more pragmatic: It’s what works in the entertainment business. As Mark Casstevens put it, “the tape doesn’t lie”: If you’re a guitar player or a comedian, what you produce is basically all that matters. If you spend too much time focusing on whether or not you’ve found your true calling, the question will be rendered moot when you find yourself out of work.”

So the first thing is to adopt a craftsman mindset. Then, you pick something that you think you can be good at (natural aptitude) and just start working on it (action bias).

Follow Your Curiosity, Not Your Passion

When choosing what to work on, it’s also important that you have a genuine curiosity for it. One of Charlie Munger’s maxims is that you should do what you find interesting, as it is hard to become good at something you are not interested in.

A deep interest in a topic makes people work harder than any amount of discipline can.

– Paul Graham

[Excerpt from his essay: “How To Work Hard”]

Curiosity is the best guide. Your curiosity never lies, and it knows more than you do about what’s worth paying attention to. If you asked an oracle the secret to doing great work and the oracle replied with a single word, my bet would be on “curiosity.”

– Paul Graham

[Excerpt from his essay: “How To Do Great Work”]

Many of the figures [powerful people and high-achievers] I had studied were mediocre students; they often came from poverty or broken homes; their parents or siblings did not display any kind of exceptional ability. We normally imagine those who achieve great things in the world as somehow possessing a larger brain or some innate talent, giving them the raw materials out of which they can transform themselves into geniuses and Masters. Based on my research this did not seem to be the case at all. Instead, this intelligence came from the intensity of the desire to learn and the process they went through to develop high-level skill.

– Robert Greene

[Excerpt from his book: Interviews with the Masters]

When you are working at something, pay special attention to things that you enjoy doing but most people don’t like. If you are able to find it, you will gain an insane edge over most people — because if you like it but most people don’t, you will naturally outwork anyone and become the best at it.

Find what feels like play to you, but looks like work to others.

– Naval Ravikant (Founder of AngelList)

[Source: Clubhouse Talk]

How to Build Skills That Compound

Another important aspect is the kind of work that you are doing. Sam Altman offered a great piece of advice on this matter:

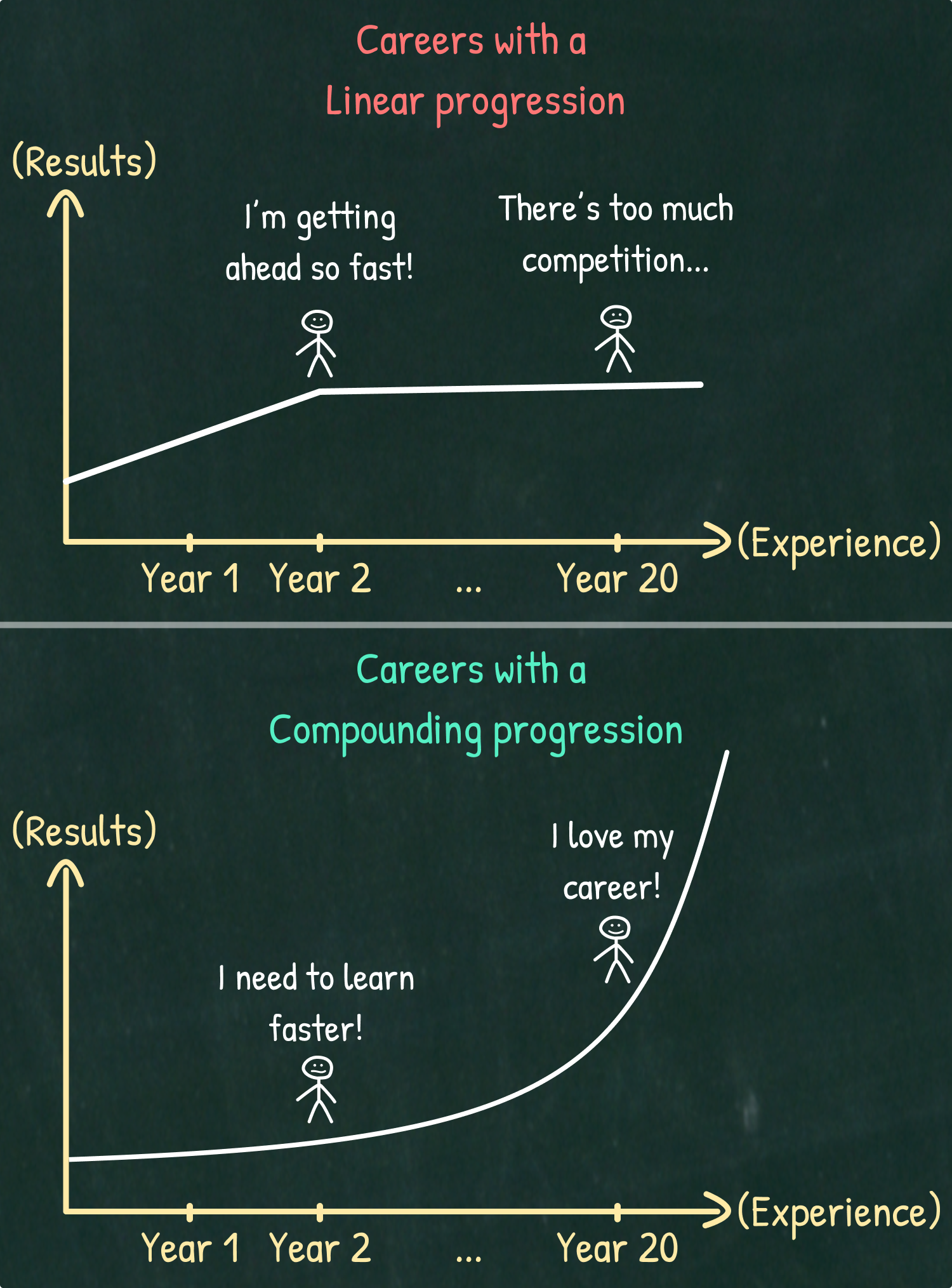

It’s important to move towards a career that has a compounding effect — most careers progress fairly linearly… You don’t want to be in a career where people who have been doing it for two years can be as effective as people who have been doing it for twenty — your rate of learning should always be high. As your career progresses, each unit of work you do should generate more and more results. There are many ways to get this leverage, such as capital, technology, brand, network effects, and managing people.

– Sam Altman (CEO of OpenAI)

[Excerpt from his blogpost: How To Be Successful]

How to Gain Your Freedom With Your Career

If you become really good at what you do in a career with a compounding effect, you can’t help but become a unique asset — you become irreplaceable. And when you get there, you have more freedom and control over your career and your life — which contributes significantly to your levels of satisfaction.

Competition is for losers.

– Peter Thiel (Co-founder of Paypal and Palantir)

[Source: Speech at Stanford]

By adopting an action bias and finding a unique skill that takes advantage of your natural abilities, you’ll be able to beat the competition completely. Robert Greene (author of The 48 Laws of Power) made this observation:

I was a little worried that young people would think the only game was being political and manipulative when really the bigger game is being so good at what you do that nobody can argue with your results.

[Source: The Guardian]

While it’s important to understand the intentions of others and be persuasive when communicating your ideas, the main focus should always be to excel at what you do. Not only will this give you an edge over others, but it will also give you freedom in your career and the ability to focus on other interests and passions as you grow.

Do What’s in Your Path With Passion, Don’t Follow Your Passion

To end this article, I want to leave you with a quote from Steve Jobs which influenced me the most to transition from the self-centered view of the passion mindset to the service-centered view of the craftsman mindset:

There’s lots of ways to be, as a person. And some people express their deep appreciation in different ways. But one of the ways that I believe people express their appreciation to the rest of humanity is to make something wonderful and put it out there.

And you never meet the people. You never shake their hands. You never hear their story or tell yours. But somehow, in the act of making something with a great deal of care and love, something’s transmitted there.

And it’s a way of expressing to the rest of our species our deep appreciation. So we need to be true to who we are and remember what’s really important to us.

[Excerpt from the book: Make Something Wonderful]

Key Takeaways – Craftsman Mindset vs. Passion Mindset

- The advice “follow your passion” naturally makes you think that you must figure out your passion and then map it to a career. However, if we look at the lives of successful individuals, we rarely see this pattern.

- Assuming that you have a passion, making a career from your passion has many issues:

- It’s hard to prioritize since you can have multiple passions.

- Passions typically change as you grow older.

- You might not be good at your passion.

- It’s a selfish view of the world, making you think about what the world can offer you, instead of what you can offer the world.

- When your passion becomes an obligation, it won’t feel as fun.

- Successful individuals (in terms of wealth and inner fulfillment) have the following in common:

- They focus on what they can offer to the world, based on their natural aptitudes and guided by their genuine curiosity.

- They build skills that compound over time, making them more unique and giving them more freedom and control.

Want More Career Advice? Check Out These Sources

If you liked this piece and want to learn more about the craftsman mindset, check out this reading and suggested content list.

- Steve Jobs’s Commencement Speech at Stanford in 2005

- So Good They Can’t Ignore You by Cal Newport

- “How To Do Great Work” by Paul Graham

- Ben Horowitz’s Commencement Address at Columbia University in 2015

- Fireside Chat with Jeff Bezos & Werner Vogels

- Dialogues by Seneca

- The 38 letters from J.D. Rockefeller to his son by John D. Rockefeller

- “How To Work Hard” by Paul Graham

- Interviews with the Masters by Robert Greene

- “How To Be Successful” by Sam Altman

- Peter Thiel’s Speech at Stanford

- Make Something Wonderful by Steve Jobs (in his own words)