Table of Contents

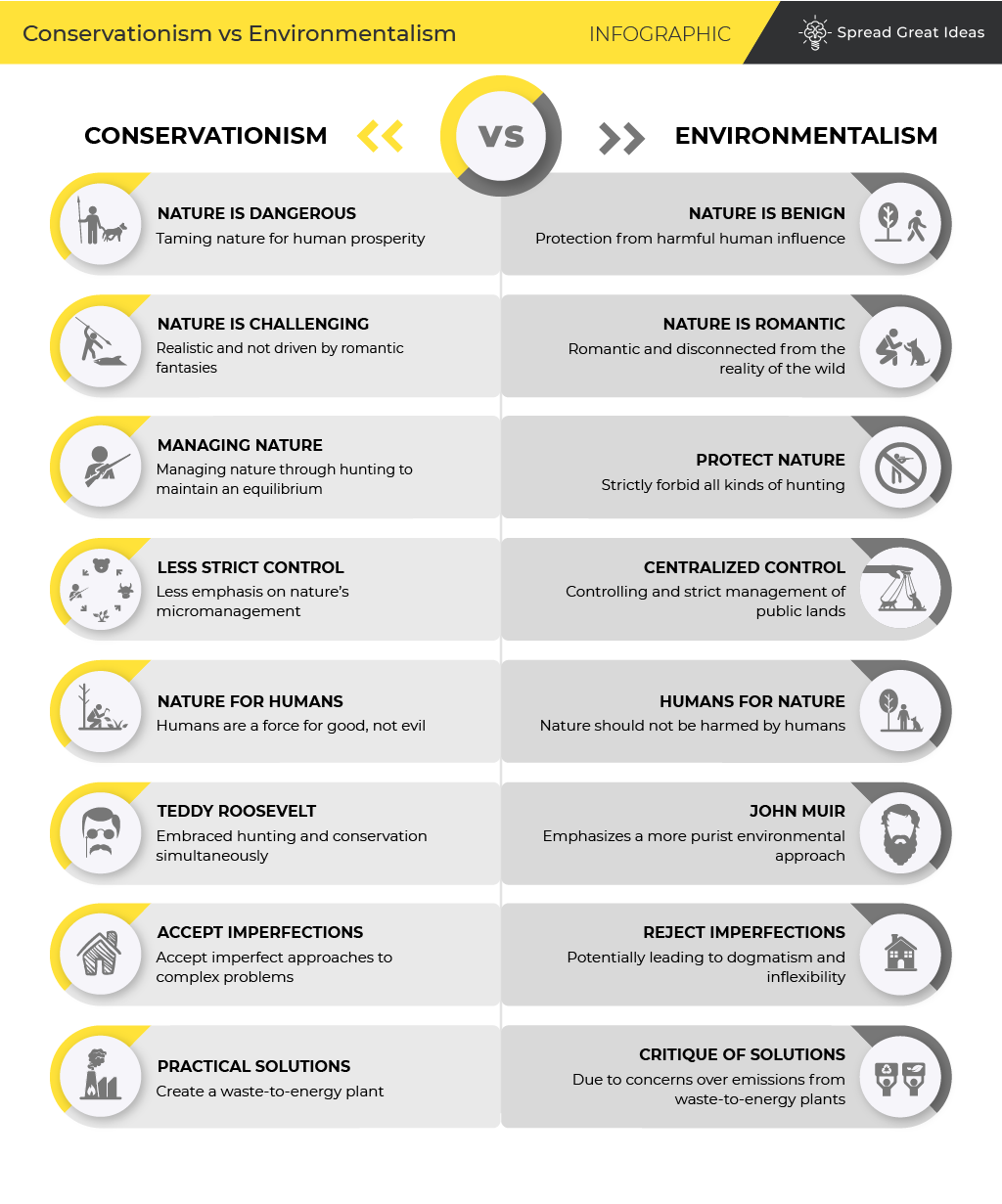

At first glance, the objective of both conservationism and environmentalism appears to be similar: To conserve our planet.

Yet how each of these philosophies approach such conservation of our planet is markedly different because they have two different presuppositions: Conservationists tend to view humans as beneficial, whereas environmentalists tend to view humans as a plague.

Consider the following question: “Is the planet dangerous, and needs to be made safe by humans for other humans? Or is the planet benign, and needs to be protected by humans from other humans?”

How one answers that question elicits a deeper belief. Conservationists by and large see the natural world as dangerous, awe-inspiring, and in need of being tamed in order to support human flourishing. Environmentalists by and large see the same natural world as benign and in need of protection from harmful human influence.

Radical Environmentalism as a Religion

Best-selling author Michael Crichton captured this dichotomy well in his speech “Environmentalism is a Religion“:

In short, the romantic view of the natural world as a blissful Eden is only held by people who have no actual experience of nature. People who live in nature are not romantic about it at all. They may hold spiritual beliefs about the world around them, they may have a sense of the unity of nature or the aliveness of all things, but they still kill the animals and uproot the plants in order to eat, to live. If they don’t, they will die.

And if you, even now, put yourself in nature even for a matter of days, you will quickly be disabused of all your romantic fantasies. Take a trek through the jungles of Borneo, and in short order you will have festering sores on your skin, you’ll have bugs all over your body, biting in your hair, crawling up your nose and into your ears, you’ll have infections and sickness and if you’re not with somebody who knows what they’re doing, you’ll quickly starve to death. But chances are that even in the jungles of Borneo you won’t experience nature so directly, because you will have covered your entire body with DEET and you will be doing everything you can to keep those bugs off you.

The truth is, almost nobody wants to experience real nature. What people want is to spend a week or two in a cabin in the woods, with screens on the windows. They want a simplified life for a while, without all their stuff. Or a nice river rafting trip for a few days, with somebody else doing the cooking. Nobody wants to go back to nature in any real way, and nobody does. It’s all talk-and as the years go on, and the world population grows increasingly urban, it’s uninformed talk. Farmers know what they’re talking about. City people don’t. It’s all fantasy.

One way to measure the prevalence of fantasy is to note the number of people who die because they haven’t the least knowledge of how nature really is. They stand beside wild animals, like buffalo, for a picture and get trampled to death; they climb a mountain in dicey weather without proper gear, and freeze to death. They drown in the surf on holiday because they can’t conceive the real power of what we blithely call “the force of nature.” They have seen the ocean. But they haven’t been in it.

Author Paul Rosenberg calls “climate change” a catechism:

It has become, to state it very bluntly, a replacement religion for a West that had abandoned Christianity. It has been taught to school children, first in Europe and now in North America, as a catechism. They call it climate change these days (global warming was simply too vulnerable a term), but the dogma is the same: humans bad, freedom bad, markets very bad, nature divine, governments the sword of righteousness.

Underpinning this belief in the planet being benign and in need of protection by humans from other humans is Rousseau’s invented concept of “the noble savage” i.e. an imaginary world in which native peoples live(d) in harmony with their surroundings and didn’t manipulate nature to their benefit. A similar belief is implicit in why many people choose to eat vegan.

Once you understand the presuppositions underpinning modern-day environmentalism—namely that humanity is a plague on our sacred planet and that the return to a simpler, more balanced time inhabited by the noble savage—then you’re able to better understand such anti-human actions like the environmentalist at AOC’s town hall advocating that “we need to eat babies to stop global warming” or people who decide they’re not having children in order to fight climate change. Talk about “minimizing human impact” lends itself to both population control and control as to what you can do on your land because you’re not to be trusted with such decisions yourself.

Conservationism: A More Pragmatic Approach to Preserving Our Planet

Look around: You don’t see conservationists talking about population control with the same fervor that you see environmentalists doing so. Nor do conservationists practicing the same degree of micromanagement as environmentalists do when it comes to what you can and cannot do on your land – let alone public land which ostensibly you “own”, or at least have a right to benefit from, as a taxpaying citizen of your country – because environmental doctrine holds that the land is sacred, irregardless of ownership, and must be “properly managed” i.e. protected from your unwashed, unenlightened ways.

The underlying reason for the self-destructive behavior by Biden and other Western leaders is that they personally, and their supporters, have bought into the Malthusian view that oil & gas production must be curtailed to deal with climate change.

— Michael Shellenberger (@ShellenbergerMD) June 27, 2022

One way in which this centralized vs. decentralized view of land management manifests itself is illustrated by how the state manages public lands. Consider the following situation in the U.S.:

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) manages fully 1/8th of all the landmass of the United States. The Bureau was created by then-President Harry S. Truman in 1946, through the combination of two existing federal agencies – the General Land Office and the Grazing Service. Most BLM land is concentrated in 12 Western states: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

There’s truth to the idea that BLM lands are largely lands that no one wanted to settle. The actual land is remnants held for homesteading that no homesteaders actually claimed. Ranchers, however, often use the land for grazing with 18,000 permits and leases held for 155 million acres. There are also over 63,000 gas and oil wells, as well as extensive coal and mineral mining. So while the land might be land that individuals don’t want to live on and farm, it is far from without value.

Who decides how public land is managed and for whose benefit again comes back to the same philosophical question: “Is the planet dangerous, and needs to be made safe by humans for other humans? Or is the planet benign, and needs to be protected by humans from other humans?”

So how do conservationists view humans and their relationship to the natural world? Many conservationists are hunters and here’s a clue as to why:

I grew up in the South, where hunting is a large part of the culture. I began learning to shoot deer and game birds at a young age. Walking through the fields with my grandfather taught me a lot about game management, habitat protection, and gun safety. I also learned respect for both the sport and the people who participate in it. It is a sport deeply rooted in conservation, tradition, and family. We eat what we kill, and as a family we take pride in trying to eat game exclusively year-round. Hunting also introduced me to a world full of interesting people and places….My grandfather shared his world with me, a world that can be difficult to understand and even seem politically incorrect. His world taught me of our responsibility to protect and conserve the habitat of wild animals and the land that has given us so much.

What is ironic is that hunters—and by extension, all American firearm owners—continue to be some of the biggest financial supporters paying to keep American wilderness wild at heart. Since 1937, there has been an 11% federal excise tax on rifles, shotguns, and ammunition and a 10% tax on pistols thanks to the Pittman-Robertson Act, which is officially known as the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act. This money is earmarked for the Department of the Interior and its wildlife preservation efforts:

A study conducted by the Fish and Wildlife Agencies found that hunters were spending somewhere between $2.8 and $5.2 billion every year on taxable items alone. This represents between $177 and $324 million in revenue generated by the Act annually…..Despite being little known outside of hardcore hunters, the Act raises more money for conservation and restoration than a number of well-known charities dedicated to the same purpose. Greenpeace International had operating expenditures of $96 million in 2017, while the Sierra Club had operating expenditures of $65 million for that same year. It’s not terribly surprising that most of the money raised to protect America’s natural resources and wildlife is done so by the very people who spend the most time in it.

One of America’s most iconic conservationists was also a lifelong, avid hunter: U.S. President Teddy Roosevelt. Born in New York City, Roosevelt fell in love with the American West and prioritized all sorts of conservation efforts—including national parks, forests, and monuments—all intended to preserve America’s natural resources as detailed in Cattle Kingdom: The Hidden History of the Cowboy West:

Life on the open range would routinely turn callow young cowboys, like Clay, into savvy cattlemen. It would take one willful, rich, squeaky-voiced dilettante from New York City named Theodore Roosevelt and endow him with the maturity and gravitas needed to succeed in national politics. “I have always said I would not have become President had it not been for my experience in North Dakota,” he would later write. “It was here the romance of my life began.”…

Despite his poor eyesight, Roosevelt was an avid sportsman hunter. He subscribed to the prevailing gentleman’s code of hunting conduct, largely English in derivation.

It stipulated that you didn’t shoot certain harmless animals, such as songbirds, for sport, and for the most part, what you shot you should eat. Exempt from this gentlemanly code were the predators—the bear, the cougar, and the wolf. In pursuit of these the hunter need show no mercy….

This bloodthirsty slaughtering of animals—wild animals that, as a devoted naturalist, Roosevelt professed to appreciate and love—comes as a jolt to today’s reader. But in the nineteenth century, an appreciation for the wilderness and a love of hunting went hand in hand, and loving animals and killing them were not contradictory concepts.

A reasonable amount of hunting was thought to be compatible with the preservation of nature. Hunting might even serve the useful purpose of regulating certain animal populations.

Furthermore, male identity at the time was colored by the desire to dominate nature. Demonstrating prowess in hunting harked back to some deeply ingrained concept of man as hunter-gatherer. It also tapped into the idea, current at the time, that Americans needed to tame their continent’s wilderness to make room for civilization. But these widely accepted notions were about to change.

In fact, Roosevelt lived through the period during which Americans, and arguably humanity as a whole, would start to transform their attitudes toward animals. It all began with Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. As the idea of natural selection spread, it knocked humans off their pedestal, putting us more on a par with other animals.

No longer was the human simply assumed to be some creature assembled by God from the dust of the earth. If the human had actually evolved from apes, then apes—and the rest of the animal kingdom—were a whole lot more like us than previously credited, and thus more deserving of humane treatment.

As Darwin himself put it, in The Descent of Man, published in 1871, “There is no fundamental difference between man and the higher mammals in their mental faculties….Even the lower animals…manifestly feel pleasure and pain, happiness and misery…Only a few persons now dispute that animals possess some power of reasoning.”…

The conservation movement would develop two branches as the new century progressed: the “wise and multiple use” conservation approach favored by Roosevelt and the more purist environmental approach favored by writers such as John Muir, Aldo Leopold, and Bob Marshall, who lobbied to protect wilderness areas for the aesthetic and recreational opportunities they presented and for the less tangible contributions they made to people’s quality of life.

If he had lived long enough, Roosevelt likely would have straddled these two branches.

A member of the National Rifle Association and a lover of expensive guns, he almost certainly would never have given up his weapons or his love of hunting.

On the other hand, he would have grasped the notion of wilderness for wilderness’ sake and championed the reintroduction of a keystone species like the gray wolf into Yellowstone, once he, like the rest of us, came to understand its role in the ecosystem. As a lifelong birder and animal naturalist, he would have embraced the science of ecology too, as it began to emerge.

Roosevelt’s ongoing exposure to the natural world inspired him towards what he called a “vigorously led life” and led him to embrace the ideals of the American West—independence, unwavering courage, and moral righteousness. He might have been patrician born and Ivy League educated, but he forged himself into something far more universal. By embracing what he had learned in the Badlands of North Dakota, he came to embody the ideal American cowboy. And I’d argue, a true conservationist more so than an environmentalist because he continually demonstrated a pragmatic streak.

Pragmatism Applied to Environmental Policy

This pragmatic streak is important because it’s a solid indicator as to where you fall at on this issue: Can you accept an imperfect solution to a complex problem? Or are you driven by a dogmatic belief that if the proposed solution isn’t perfect that it’s better to eschew it altogether and instead repeat inaccurate, eco-pocalyptic predictions?

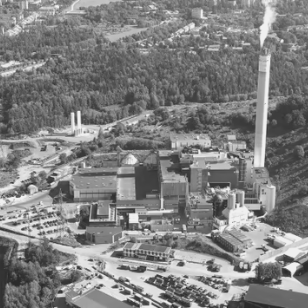

Consider the case of a country I used to live in, Sweden, which is celebrated as being environmentally-friendly and also burns about half their trash in one of 33 waste-to-energy plants—an inconvenient fact which some environmentalists take issue with, as you’ll see below:

Close to half of Sweden’s household trash is burned in the nation’s 33 waste-to-energy, or WTE, plants. Those facilities provide heat to 1.2 million Swedish households and electricity for another 800,000, according to Anna-Carin Gripwall, Avfall Sverige’s director of communications.

“We live in a cold country so we need the heating,” Gripwall explains in a Skype interview.

The heat from burning garbage can be used effectively in Sweden because half of the nation’s buildings now rely on district heating, in which they’re warmed by a common heating plant instead of running their own boilers or furnaces, as this article from Euroheat & Power explains. In one Swedish city, Gothenburg, burning waste heats 27 percent of the city, according to this 2011 case study from C40.org.

WTE plants have been a subject of controversy in the U.S., as this Feb. 27, 2018, article from The Conversation details, because of concern over toxic emissions and carbon dioxide. “Burning trash is not a form of recycling,” the article’s author, Ana Baptista, chair of the Environmental Policy & Sustainability Management Program at the New School, writes in an email.

A 2017 report by British-based environmental consultancy Eunomia and Resource Media, which didn’t count waste-to-energy as recycling either, ranked Sweden just 12th in the world in recycling, behind countries such as the Netherlands and Luxembourg.

But in Sweden, environmental activist Gaffney sees WTE as having more upsides. “It is not a perfect solution,” he explains. “Toxic chemicals are now very low due to stringent regulations. Carbon dioxide emissions though are an issue. But are they worse or better than fossil fuels? Much biomass waste will soon release greenhouse gases anyway as it decomposes, and this is part of the natural carbon cycle. When you do the calculation, emissions from burning waste are similar to natural gas.”

So the next time you’re contemplating whether you’re more akin to a conservationist or an environmentalist, consider how you view your relationship to our planet: “Is the planet dangerous, and needs to be made safe by humans for other humans? Or is the planet benign, and needs to be protected by humans from other humans?”

It’s not an either/or question, per se. But how you think about it and how dogmatically you identify with one position will give you insight into how you view your relationship to our planet.

A Visual Representation