Table of Contents

It’s almost self-evident that we should all try to win in life rather than win an argument. We all obviously want tangible returns and ultimate real success in life, rather than winning on words. So the right question is not how to win an argument, but how to win in life.

You do not want to win an argument. You want to win.

– Nassim Nicholas Taleb (Best-selling Author, Former Options Trader, and Risk Analyst)

[From his book – Skin in the Game]

So, why is it that so many people seem to focus on winning arguments (even at the expense of real long-term success)? From a rational standpoint, it just doesn’t make sense. But when you start digging into human biases and unconscious motivations, the clues begin to emerge.

There are at least five main reasons (grounded in psychology literature and the experiences of remarkable individuals whom I consider to have “won at life,” such as Naval Ravikant, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Warren Buffet, and Charlie Munger) for why we would choose to engage in such irrational behavior. And if you haven’t thought about these reasons, then odds are that you, too, are prioritizing winning arguments over winning in life — and you’re not even aware of it since it’s all going on outside the limits of our conscious and rational part of the brain!

In this essay, we will explore these five reasons (which are essentially “leaks” from biases and subconscious processes at work in your behavior when having a discussion) and come up with heuristics and solutions to help us counterbalance these biases and unconscious motivations so that we can actually prioritize winning in life over winning arguments.

Reason #1: The Identity Leak

An “Identity Leak” occurs when we personally identify with the subject of the argument. When this happens, we stop thinking rationally about the issue, and it becomes a personal battle where the only goal is to win the argument — rather than seek the truth.

As soon as the identity element comes into play in an argument, you’ve already lost — because when the truth-seeking goal is killed, progress is killed too. If we want to have an honest and objective discussion, identity can never enter the dialogue.

I think creating identities and labels locks you in and keeps you from seeing the truth.

“To be honest, speak without identity.”

I used to identify as libertarian, but then I would find myself defending positions I hadn’t really thought through because they’re a part of the libertarian canon. If all your beliefs line up into neat little bundles, you should be highly suspicious.

I don’t like to self-identify on almost any level anymore, which keeps me from having too many of these so-called stable beliefs.

– Naval Ravikant (Founder of AngelList)

[Book – The Almanack of Naval Ravikant, by Eric Jorgenson]

This tendency to defend your identity instead of seeking truth is particularly strong when you belong to a group. Because groups survive by consensus rather than truth, thus if you belong to a group but are a truth-seeker, you will likely get ostracized by the group sooner or later — you will be seen as a threat to the survival of the group.

Individuals search for truth but groups search for consensus.

– Naval Ravikant

[From his blogpost – Groups Search for Consensus, Individuals Search for Truth]

How to Overcome an Identity Leak?

The first thing, which is necessary but not sufficient, to avoid arguing with an identity is to avoid speaking for a group. Remember: Only the individual can search for truth.

Once you make sure you are not in a group context, the best piece of advice I’ve ever heard to avoid the “Identity Leak” comes from the renowned music producer Rick Rubin. In a conversation with the author Ryan Holiday, he said:

Always make a model. Don’t talk about it… Show what it is that you’re doing. Don’t say the kind of article you want to write, write the article, show me the article. Then, we talk about the article.

What’s great about that is it takes it out of the personal, you know, if you have an idea, it’s your idea. And then we could argue about your idea and that’s personal. Once it’s on paper, it’s outside of you. And it’s this thing that we’re collaborating on together to make it be the best it could be. We’re not talking about your idea. Now we’re talking about: Is this sentence the best sentence it could be? That’s not a slight against you. That’s we’re working together to make this sentence the best it could be.

The bottom line is this: If you want to speak without identity, always try to externalize the discussion to some model or prototype — so that there is a physical separation between you and what’s being discussed.

Reason #2: The Ego Leak

It’s no mystery that winning an argument feeds your ego. And it’s also no mystery that feeding your ego feels good (or that deflating it causes discomfort). Thus, it shouldn’t surprise us that we often neglect objectivity in discussions when it conflicts with our ego.

The opposite of an ego-driven discussion is a truth-driven discussion. And if you want to win in life, truth and objectivity must be your only goal. In the words of Naval Ravikant, “You can only make meaningful change and progress when you’re starting with the truth.”

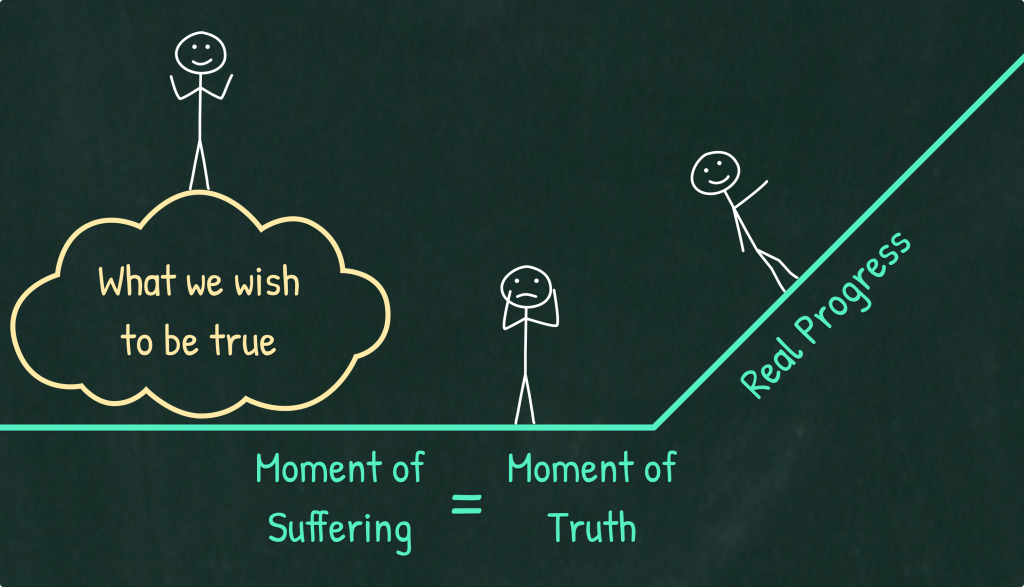

One definition of a moment of suffering is “the moment when you see things exactly the way they are.” This whole time, you’ve been convinced your business is doing great, and really, you’ve ignored the signs it’s not doing well. Then, your business fails, and you suffer because you’ve been putting off reality. You’ve been hiding it from yourself.

The good news is, the moment of suffering—when you’re in pain—is a moment of truth. It is a moment where you’re forced to embrace reality the way it actually is. Then, you can make meaningful change and progress. You can only make progress when you’re starting with the truth.

The hard thing is seeing the truth. To see the truth, you have to get your ego out of the way because your ego doesn’t want to face the truth. The smaller you can make your ego, the less conditioned you can make your reactions, the less desires you can have about the outcome you want, the easier it will be to see the reality.

“What we wish to be true clouds our perception of what is true. Suffering is the moment when we can no longer deny reality.”

– Naval Ravikant

[Book – The Almanack of Naval Ravikant, by Eric Jorgenson]

How to Overcome the Ego Leak

First of all, it is important to understand what the ego really is:

Our egos are constructed in our formative years—our first two decades. They get constructed by our environment, our parents, society. Then, we spend the rest of our life trying to make our ego happy. We interpret anything new through our ego: “How do I change the external world to make it more how I would like it to be?”

– Naval Ravikant

[Book – The Almanack of Naval Ravikant, by Eric Jorgenson]

There are two ways of overcoming the “Ego Leak”:

1. Reduce your overall ego

The key to reducing one’s ego is self-examination. My favorite ways to examine my thoughts and behaviors are to meditate and read books on philosophy. Meditation is great for developing awareness of the fact that you’re constantly thinking, and reading philosophy books is great for challenging much of what you’re constantly thinking about.

The more self-aware you are, the more understanding you have about yourself and this mental construction (the ego), and the more you can control your ego.

The unexamined life is not worth living.

– Socrates

2. Keep your ego from entering the discussion

The key here is putting all your attention to listening to the other person instead of having your attention scattered between listening and judging the other person’s arguments.

The more you can listen without immediate judgment, the more you will keep your ego out of the discussion (and the more you will learn from the other person).

Reason #3: The Instant-Gratification Leak

We have a natural tendency to overvalue things where the pay-off (or benefit) is in the short term and undervalue things where the pay-off is in the long term.

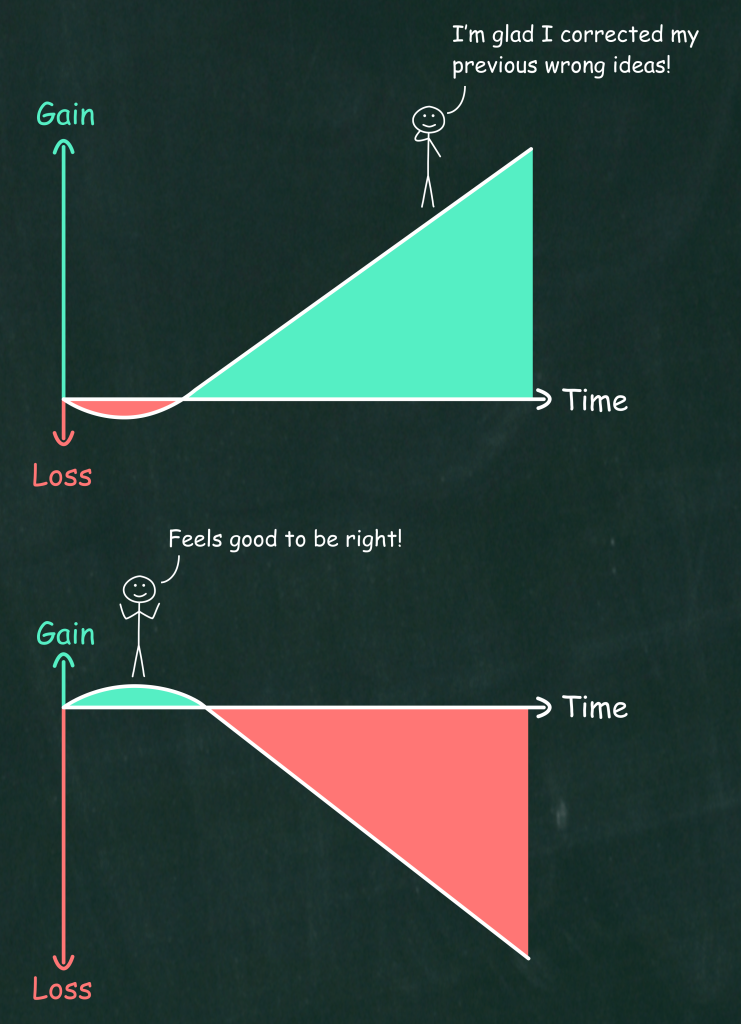

Winning arguments is all about the short term: You get the ego high, you avoid the shame of accepting being wrong in public (more on that on Reason #5: The Status Leak), and you avoid the internal discomfort that occurs when you change your mind (more on that on Reason #4: The Consistency Leak).

On the other hand, winning in life is all about the long term: You willingly lean into the pain of accepting being wrong in public and deflate your ego, but in the long term, your judgment will be much better (this is the pay-off), and consequently, you will be much more successful in life.

How to Overcome the Instant-Gratification Leak

On a Periscope livestream, Naval Ravikant gave an insightful explanation and advice on this issue:

[A] decision-making heuristic that I use is: If you have two choices to make, such as

- “Do I tell this person A or do I tell them B?”

- “Do I take job A or job B?”

- “Do I make this sacrifice now, or do I go ahead and do what I want?”

If you have two choices, and they’re relatively equal choices (it looks 50-50 to you) and you can’t decide, take the path that is more difficult and more painful in the short-term. Because what’s actually going on is: One of these paths requires short-term pain, and the other one maybe requires pain further out in the future. And what your brain is doing (through conflict avoidance) is it’s trying to push off the short-term pain. And by definition, if the two are even (50-50) and one has short-term pain, that means it has long-term gain. And by the law of compound interest, the long-term gain is where you want to go towards anyway.

So, your brain is overvaluing the side that has the short-term happiness, and it’s trying to avoid the one with short-term pain. So, you have to cancel that tendency out (and it’s a powerful subconscious tendency) by leaning into the pain.

As most of you know, most of the gains in life come from suffering in the short-term, so you can get paid in the long-term. Working out (for me) is not fun. I suffer in the short-term. I feel that pain, but then in the long-term, I’m better off because I have muscles or I’m healthier. In the same way, if I am reading a book and I’m getting confused — like I can’t understand what’s going on — that’s just like working out and the muscle getting sore, but [now] is my brain being overwhelmed. But in the long run I’m getting smarter, because I’m absorbing new concepts at the edge of my capability.

So, you generally want to lean into things that have short-term pain, but have long-term gain. My trainer, Jerzy Gregorek (also known as the creator of The Happy Body) has a beautiful short saying where he says: “Hard choices, easy life. Easy choices, hard life.” So, what he means by that is:

- If you make the hard choices in the short-term (e.g. “I shouldn’t eat bad carbs or processed foods.” Or “I should go ahead and do the workout — which is difficult and I don’t feel like doing it”), then in the long-term you’re going to have an easy life.

- But if you make the easy choices in the short-term (e.g. “I’m going to stay out drinking, I’m going to go party, I’m not going to do my work right now, I’m not going to meditate”…), then in the long-term you’re going to have a very difficult life. You will not have built up that self-discipline.

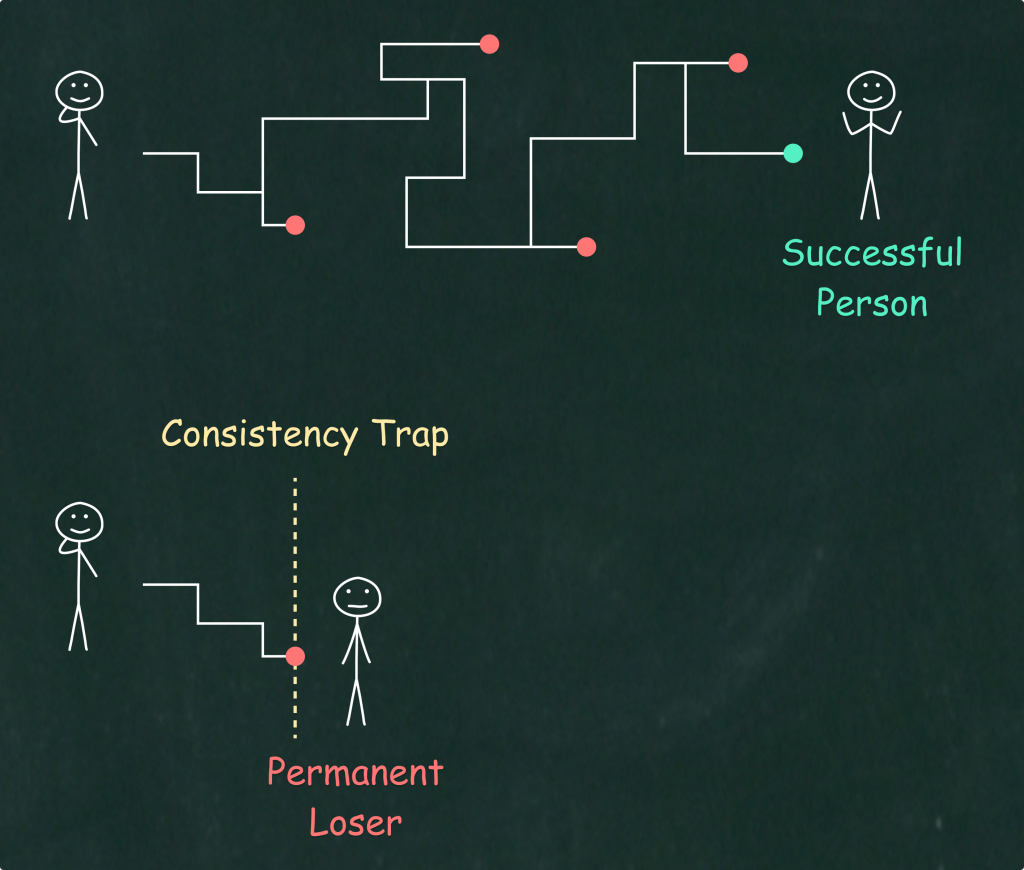

Reason #4: The Consistency Leak

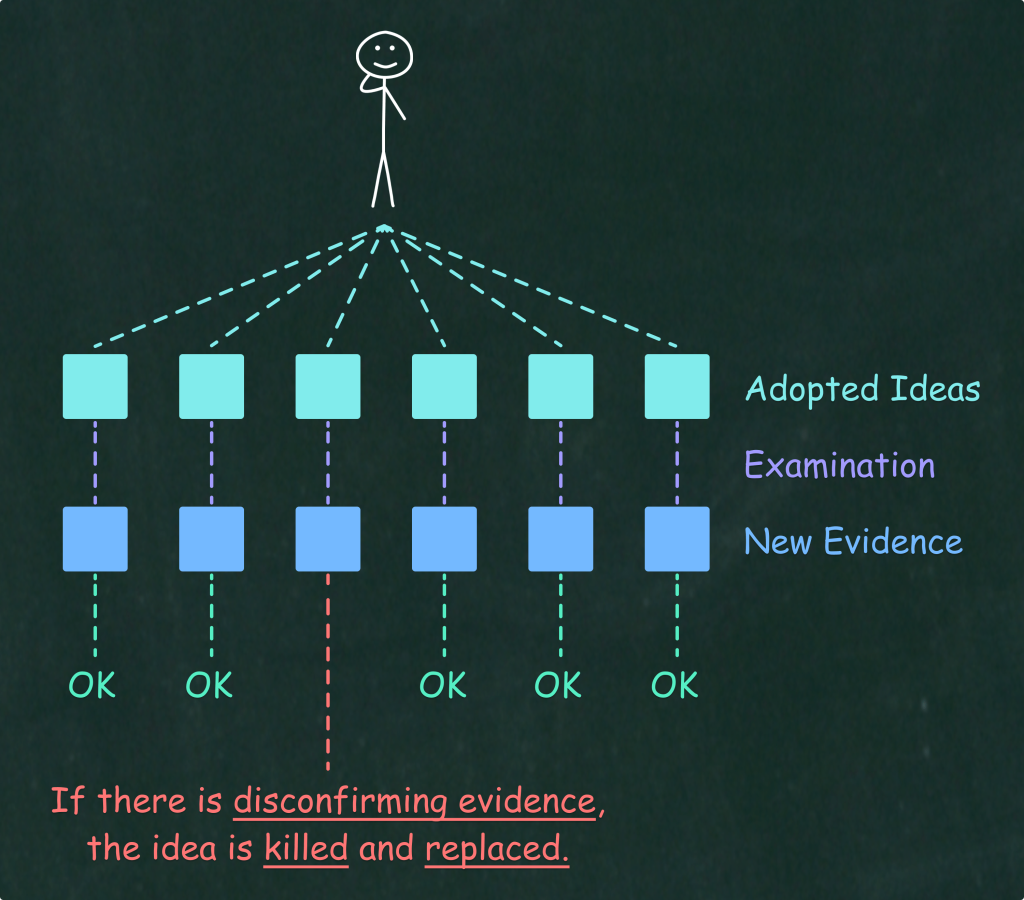

Our human consistency bias makes it hard for us to listen and accept disconfirming evidence in the middle of a debate. We have naturally evolved to be averse to any sort of inconsistencies — whether in actions, ideas, or beliefs.

Warren Buffet tells the story of how Charles Darwin always had a notepad with him so that when he identified disconfirming evidence, he could write it down quickly because he knew that we are extremely prone to forget about anything that is inconsistent with our thinking.

If we look at the greatest scientists and entrepreneurs, we can see that they were all open to changing their minds as they imbibed new information in the process. They all had the willingness to be wrong in the short term in order to be right in the long term. In other words, they were not interested in winning arguments but in ultimately winning in their science or business projects. Here are some of them, picked from the book The Elon Musk Blog Series (written by Tim Urban):

“To myself I am only a child playing on the beach, while vast oceans of truth lie undiscovered before me.”

– Isaac Newton

“I was born not knowing and have had only a little time to change that here and there.”

– Richard Feynman

“Every sentence I utter must be understood not as an affirmation, but as a question.”

– Niels Bohr

“You should take the approach that you’re wrong. Your goal is to be less wrong.”

– Elon Musk

How to Overcome the Consistency Leak?

From this moment on, declare war on the word “certainty.” Rather than clinging with certainty to ideas and beliefs, start the habit of assigning probabilities to them — so that you can give yourself permission to always question your current ideas and beliefs and be ready to adopt an alternative idea when the evidence favors it.

If you cultivate an attitude of relentless curiosity and self-criticism, you will counterbalance this natural predisposition to be consistent with your previous ideas and beliefs. You will even free yourself from your own past statements.

One author from antiquity who provides us evidence of such thinking is the garrulous Cicero. He preferred to be guided by probability than allege with certainty—very handy, some said, because it allowed him to contradict himself. This may be a reason for us, who have learned from Popper how to remain self-critical, to respect him more, as he did not hew stubbornly to an opinion for the mere fact that he had voiced it in the past. Indeed your average literature professor would fault him for his contradictions and his change of mind.

– Nassim Nicholas Taleb

[From his book – Fooled by Randomness]

Robert Cialdini, author of the best-seller book Influence, also proposed two approaches for noticing when the consistency bias leaks into our decision-making. Shane Parrish (author of the blog Farnam Street) explains these two approaches from Cialdini:

The first one is to listen to our stomachs. Stomach signs display themselves when we realize that the request being pushed is something we don’t want to do.

He [Robert Cialdini] recalls a time when a beautiful young woman tried to sell him a membership he most certainly did not need. He writes:

“I remember quite well feeling my stomach tighten as I stammered my agreement. It was a clear call to my brain, “Hey, you’re being taken here!” But I couldn’t see a way out. I had been cornered by my own words. To decline her offer at that point would have meant facing a pair of distasteful alternatives: If I tried to back out by protesting that I was not actually the man-about-town I had claimed to be during the interview, I would come off a liar; trying to refuse without that protest would make me come off a fool for not wanting to save $1,200. I bought the entertainment package, even though I knew I had been set up. The need to be consistent with what I had already said snared me.”

But then eventually he came up with the perfect counter-attack for later episodes, which allowed him to get out of the situation gracefully:

“Whenever my stomach tells me I would be a sucker to comply with a request merely because doing so would be consistent with some prior commitment I was tricked into, I relay that message to the requester. I don’t try to deny the importance of consistency; I just point out the absurdity of foolish consistency. Whether, in response, the requester shrinks away guiltily or retreats in bewilderment, I am content. I have won; an exploiter has lost.”

The second approach concerns the signs that are felt within our heart and is best used when it is not really clear whether the initial commitment was wrongheaded.

Imagine you have recognized that your initial assumptions about a particular deal were not correct. Here it helps to ask one simple question:

“Knowing what I know, if I could go back in time, would I make the same commitment?”

Ask it frequently enough and the answer might surprise you.

Reason #5: The Status Leak

When you make a public proclamation, people expect you to be consistent with it and defend it. Society looks down on people who change their minds. This might have been a good proxy (for detecting honesty and intelligence) in prehistoric times — when the creation of new knowledge was essentially nonexistent (within a generation), and nothing really changed at all, but in modern times, new knowledge and complexity are growing at an exponential rate, and lots of things are changing quickly — so, it should be the norm to change our minds frequently.

Any year that passes in which you don’t destroy one of your best-loved ideas is a wasted year.

– Charlie Munger (Ex-Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway)

We are wired to defend our (publicly stated) ideas and beliefs just to keep our social status from declining, but the wisest and most successful people realize that the only way to make progress is to identify mistakes and course-correct immediately — and they are willing to pay the status price for that.

In his book Fooled by Randomness, Nassim Nicholas Taleb explains this perfectly (with some funny stories):

Modern times provide us with a depressing story. Self-contradiction is made culturally to be shameful, a matter that can prove disastrous in science. Marcel Proust’s novel In Search of Time Lost features a semiretired diplomat, Marquis de Norpois, who, like all diplomats before the advent of the fax machine, was a socialite who spent considerable time in salons. The narrator of the novel sees Monsieur de Norpois openly contradicting himself on some issue (some prewar rapprochement between France and Germany). When reminded of his previous position, Monsieur de Norpois did not seem to recall it. Proust reviles him:

“Monsieur de Norpois was not lying. He had just forgotten. One forgets rather quickly what one has not thought about with depth, what has been dictated to you by imitation, by the passions surrounding you. These change, and with them so do your memories. Even more than diplomats, politicians do not remember opinions they had at some point in their lives and their fibbings are more attributable to an excess of ambition than a lack of memory.”

Monsieur de Norpois is made to be ashamed of the fact that he expressed a different opinion. Proust did not consider that the diplomat might have changed his mind. We are supposed to be faithful to our opinions. One becomes a traitor otherwise.

Now I hold that Monsieur de Norpois should be a trader. One of the best traders I have ever encountered in my life, Nigel Babbage, has the remarkable attribute of being completely free of any path dependence in his beliefs. He exhibits absolutely no embarrassment buying a given currency on a pure impulse, when only hours ago he might have voiced a strong opinion as to its future weakness. What changed his mind? He does not feel obligated to explain it.

The public person most visibly endowed with such a trait is George Soros. One of his strengths is that he revises his opinion rather rapidly, without the slightest embarrassment. The following anecdote illustrates Soros’ ability to reverse his opinion in a flash. The French playboy trader Jean-Manuel Rozan discusses the following episode in his autobiography (disguised as a novel in order to avoid legal bills).The protagonist (Rozan) used to play tennis in the Hamptons on Long Island with Georgi Saulos, an “older man with a funny accent,” and sometimes engage in discussions about the market, not initially knowing how important and influential Saulos truly was. One weekend, Saulos exhibited in his discussion a large amount of bearishness, with a complicated series of arguments that the narrator could not follow. He was obviously short the market. A few days later, the market rallied violently, making record highs. The protagonist worried about Saulos, and asked him at their subsequent tennis encounter if he was hurt. “We made a killing,” Saulos said. “I changed my mind. We covered and went very long.”

It was this very trait that, a few years later, affected Rozan negatively and almost cost him a career. Soros gave Rozan in the late 1980s $20 million to speculate with (a sizeable amount at the time), which allowed him to start a trading company (I was almost dragged into it). A few days later, as Soros was visiting Paris, they discussed markets over lunch. Rozan saw Soros becoming distant. He then completely pulled the money, offering no explanation. What characterizes real speculators like Soros from the rest is that their activities are devoid of path dependence. They are totally free from their past actions. Every day is a clean slate.

How to Overcome the Status Leak?

Develop an inner self-respect and learn to care less about what other people think of you. Develop an indifference to things that are outside of your control — such as expectations from others. If you want to dig deeper into this strategy, I recommend you check out Stoicism.

You have no responsibility to live up to what other people think you ought to accomplish. I have no responsibility to be like they expect me to be. It’s their mistake, not my failing.

– Richard Feynman (Theoretical Physicist)

Courage isn’t charging into a machine gun nest.

Courage is not caring what other people think.– Naval Ravikant

[Book – The Almanack of Naval Ravikant, by Eric Jorgenson]

Additionally, realize that the essence of all great souls is to be willing to contradict themselves in pursuit of something bigger than themselves. This is captured beautifully by the renowned essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson in his famous essay Self-Reliance:

A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines. With consistency a great soul has simply nothing to do. He may as well concern himself with his shadow on the wall. Speak what you think now in hard words, and to-morrow speak what to-morrow thinks in hard words again, though it contradict every thing you said to-day. — ‘Ah, so you shall be sure to be misunderstood.’ — Is it so bad, then, to be misunderstood? Pythagoras was misunderstood, and Socrates, and Jesus, and Luther, and Copernicus, and Galileo, and Newton, and every pure and wise spirit that ever took flesh. To be great is to be misunderstood.

Summary Guide: How to Go From Winning Arguments to Winning in Life

1. Speak without identity. How? Avoid being part of a group, and try to externalize the debate to some model or prototype.

2. Either reduce your overall ego (through self-examination) or keep it from entering the debate (by placing all your attention on listening to the other person rather than forming quick judgments in your mind).

3. Be willing to tolerate the short-term pain of being wrong so that you can get the long-term gain of improved judgment and overall success.

4. Don’t be a prisoner of your past actions and ideas. As new information comes your way, it is completely rational to change your mind about something. Never settle, question everything, welcome disconfirming evidence, avoid certainty, and think probabilistically.

5. Realize that other people’s expectations are their problem, not yours. You have no responsibility to fit within their preconceptions of how you should behave or think. You only have a responsibility to yourself to become the best that you can be — and ironically, to accomplish that, it is imperative that you don’t care what others think of you.

If You Liked This Essay, Check Out These Sources

- Skin in the Game, by Nassim Nicholas Taleb

- Cognitive Bias Quotes: The Importance of Realizing One’s Biases

- Libertarian

- The Almanack of Naval Ravikant, by Eric Jorgenson

- Why Only Individuals Can Search For Truth

- Groups Search for Consensus, Individuals Search for Truth

- Rick Rubin on The Creative Act, Overcoming Ego, and Enjoying the Process

- Naval Ravikant | Rules to make better decisions

- Commitment and Consistency Bias

- 1998 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting (Full Version)

- The Elon Musk Blog Series, by Tim Urban

- Fooled by Randomness, by Nassim Nicholas Taleb

- Influence, by Robert Cialdini

- Self-Reliance, by Ralph Waldo Emerson

Critical Thinking & Free Speech Quotes: Speak Freely, Think Clearly, Live Intentionally

Free speech and critical thinking go hand in hand. One gives us the right to speak our minds; the other gives us the ability to make sense of the world.…