Table of Contents

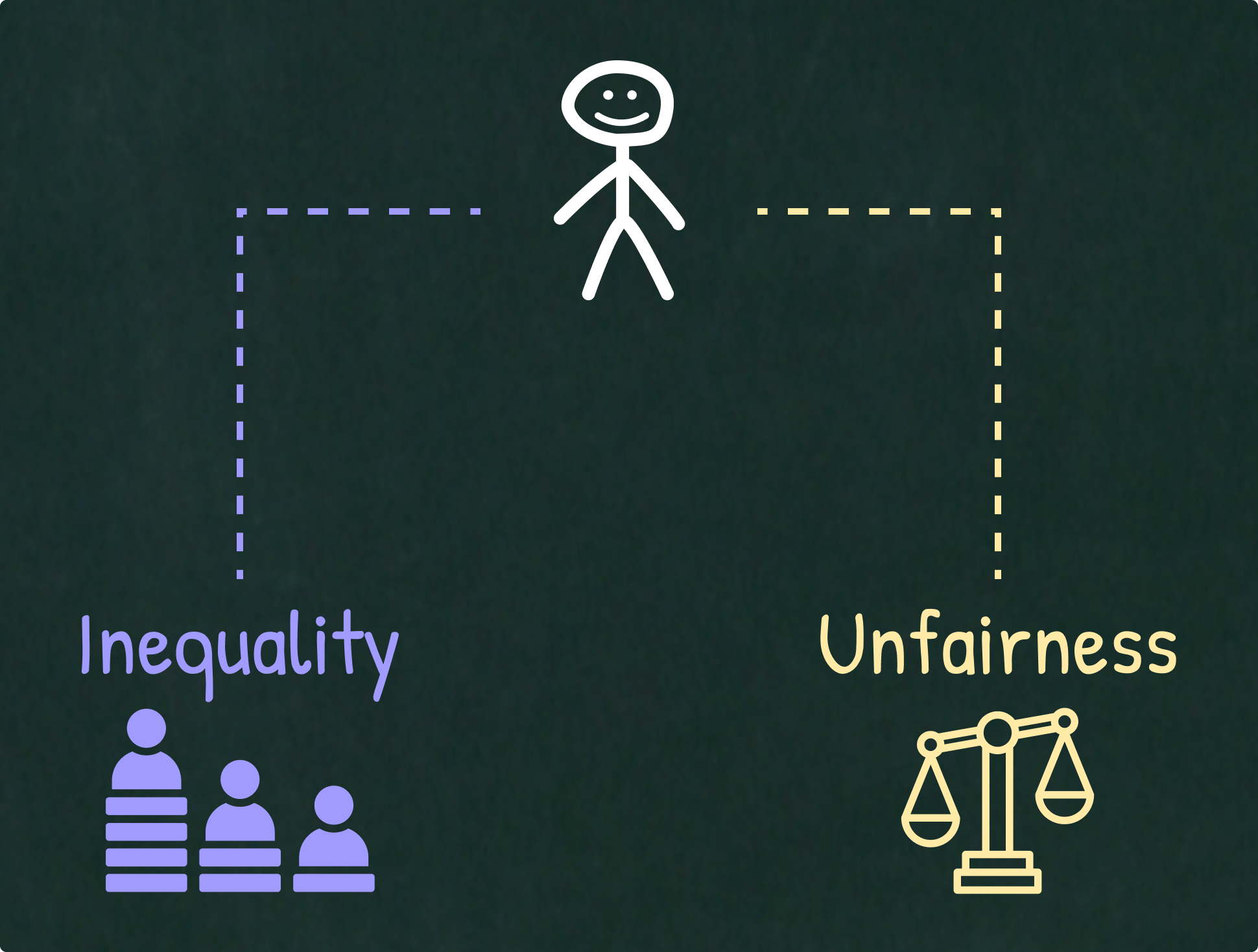

Most people tend to conflate inequality with unfairness, especially within the economic context. But these terms are far from being synonymous.

Most people tend to conflate inequality with unfairness, especially within the economic context. But these terms are far from being synonymous.

In this essay, we will objectively break down each term, study how they relate to one another, and (perhaps!) improve your relationship to wealth creation.

As a little hint to what’s coming, I’ll say that there is indeed a connection between inequality and unfairness, but there is only one kind of inequality that is actually unfair (rather than any inequality). And this remains true in any domain — whether in sports, business, politics, academia, etc.

The ideas in this essay are heavily influenced by thinkers such as Paul Graham (Co-founder of YC), Naval Ravikant (Co-founder of AngelList) and Charlie Munger (former Vice-Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway).

Now, let’s get on with the task! (Or if you want to go straight to the Key Takeaways section, just click here.)

The One Kind of Inequality That Is Actually Unfair

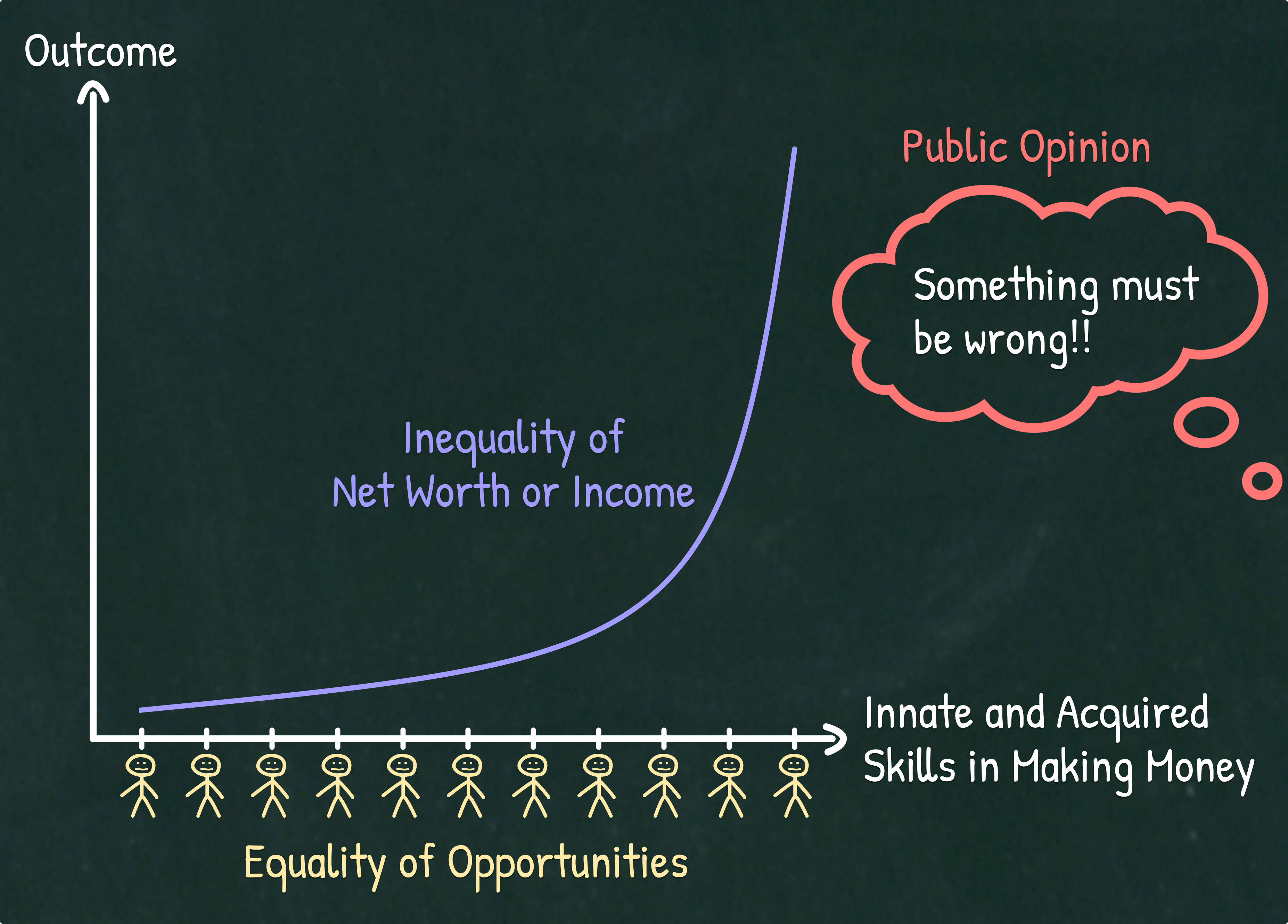

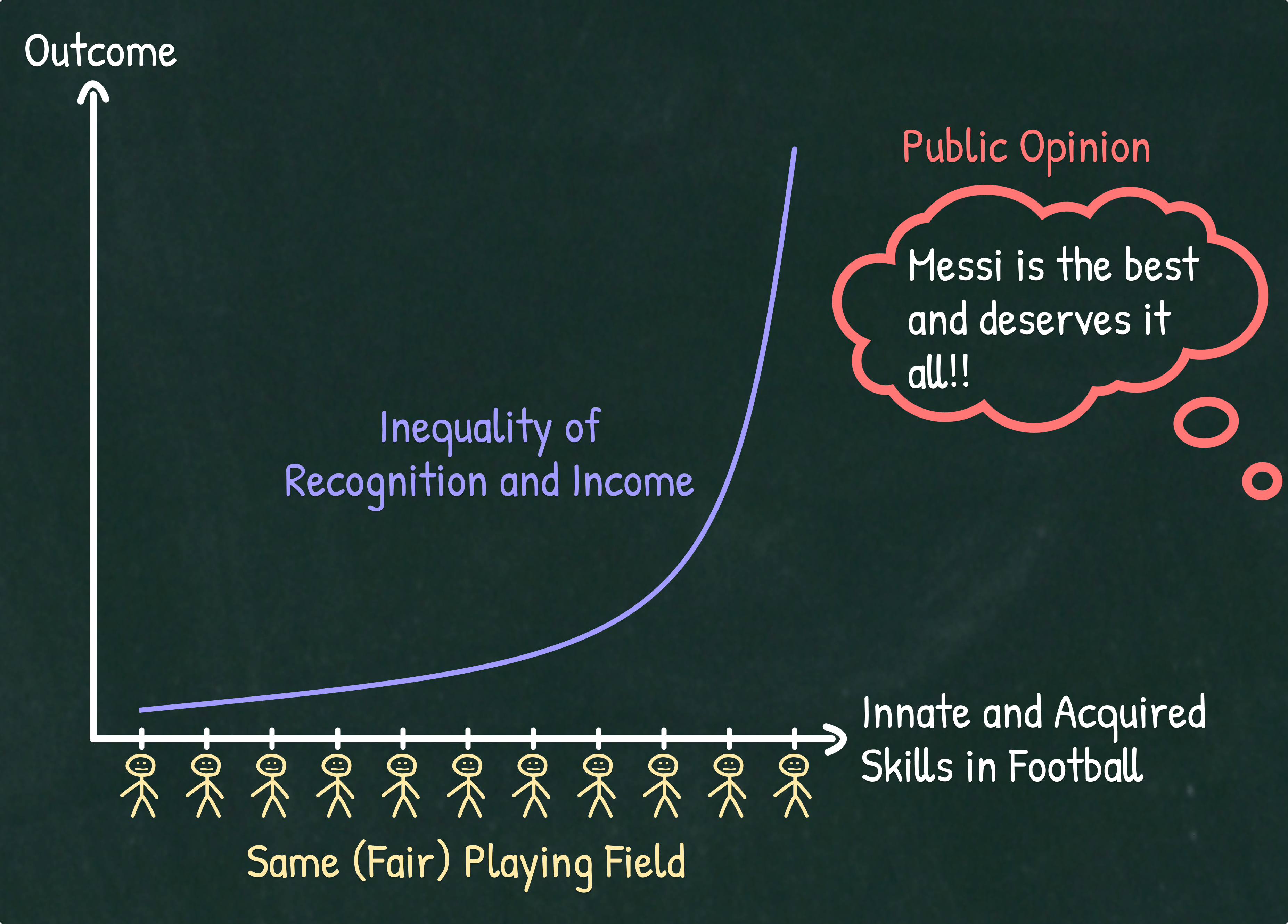

We are naturally drawn to meritocratic endeavors. We don’t have an issue with the fact that some people get way more recognition and acclaim than others (inequality of outcome), so long as they play under the same rules as everyone else (fairness).

Let’s take football — the European kind — as an example. Lionel Messi, despite his size, is incredibly blessed with raw talent, and through a combination of his natural talent, sheer force of will, good luck, and mentorship, has turned himself into one of the world’s greatest footballers of all time. Nobody is upset by the fact that Messi is getting almost infinitely more recognition than the 5th greatest football player.

Nassim Taleb wrote in his book The Black Swan: “The inequity comes when someone perceived as being marginally better gets the whole pie.” But, as we see, we do not have any issue with this type of inequality because of how we perceive the playing field.

What we truly care about is that the playing field is equal. Each side gets the same amount of time. The goal sizes are the same. The ball is the same. And hopefully, minus occasional human error by the referee (although this is becoming less and less thanks to VAR) the rules are applied the same. Who wins is based on who played the best according to the agreed-upon rules which are equally applied to all participants. Thus, you have a fair outcome despite differences among the player’s skills — nobody is trying to handicap Argentina by saying Messi can only run backwards.

If we boil it down to the essence, we see that humans do not just accept, but fanatically love games where the “playing field” is the same for everyone and there are clear winners and losers (despite winners getting outsized rewards compared to the second or third place competitors). The only kind of inequality that we perceive as unfair is inequality in the playing field — for instance, when a team or player is favored at the expense of others.

Let’s now leave the sports analogy and translate these concepts of inequality and unfairness to the economic domain. The playing field is the marketplace of buyers and sellers; the referee is the judiciary which resolves disputes in a timely and consistent manner, enforces contracts, and upholds the rule of law; and the players are you and I. It’s here in the economic domain that the only kind of inequality that is unfair is the inequality of opportunities.

Why Equality of Opportunities Is Not Enough (Although It Should Be)

It would be easy to think now that a free market with a robust system of creative destruction functioning within a legal framework which guarantees that everyone has an opportunity for self-actualization (equality of opportunities insofar as the law is concerned) would be enough to change people’s mind about the “money game” — which is mostly seen as unfair and even wrong — but it is far from enough.

Paul Graham noticed this issue and went deep into it to figure out what’s really going on.

What he discovered is eye-opening, to say the least. In his book Hackers and Painters, he wrote:

When people care enough about something to do it well, those who do it best tend to be far better than everyone else. There’s a huge gap between Leonardo and second-rate contemporaries like Borgognone. You see the same gap between Raymond Chandler and the average writer of detective novels. A top-ranked professional chess player could play ten thousand games against an ordinary club player without losing once.

Like chess or painting or writing novels, making money is a very specialized skill. But for some reason we treat this skill differently. No one complains when a few people surpass all the rest at playing chess or writing novels, but when a few people make more money than the rest, we get editorials saying this is wrong.

Why? The pattern of variation seems no different than for any other skill. What causes people to react so strongly when the skill is making money?

I think there are three reasons we treat making money as different: The misleading model of wealth we learn as children (i.e. that wealth is a zero-sum game); the disreputable way in which, till recently, most fortunes were accumulated (i.e. by stealing, either through direct confiscation or corruption); and the worry that great variations in income are somehow bad for society. As far as I can tell, the first is mistaken, the second outdated, and the third empirically false. Could it be that, in a modern democracy, variation in income is actually a sign of health?

Why Do We Treat The Skill of Making Money Differently From Other Skills?

Let’s now analyze each of the reasons that Paul Graham mentioned.

Mistaken Belief #1: Wealth Is a Zero-sum Game

When I was five I thought electricity was created by electric sockets. I didn’t realize there were power plants out there generating it. Likewise, it doesn’t occur to most kids that wealth is something that has to be generated. It seems to be something that flows from parents.

Because of the circumstances in which they encounter it, children tend to misunderstand wealth. They confuse it with money. They think that there is a fixed amount of it. And they think of it as something that’s distributed by authorities (and so should be distributed equally), rather than something that has to be created (and might be created unequally).

– Paul Graham

[From his Book – Hackers and Painters]

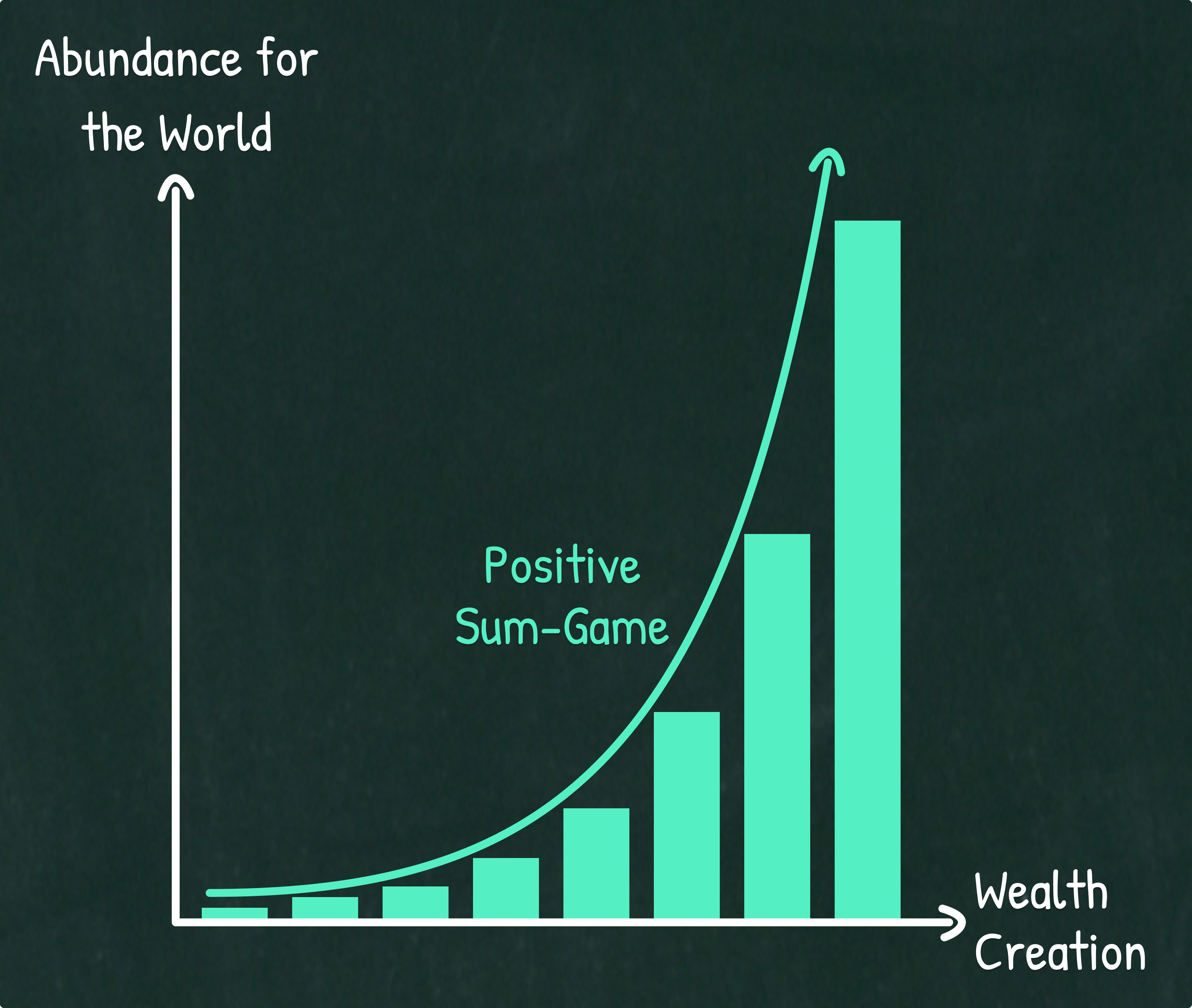

As we see, wealth creation is not a zero-sum game. Wealth creation is about making abundance for the world i.e. making everyone better-off.

Why is this the case? Because wealth ≠ money. Money is a medium of exchange, a unit of account, and a store of value. It represents the unit of measure one needs to trade for goods or services. Wealth, on the other hand, is a broader concept that measures the accumulation of valuable resources or assets one owns (minus all debts). Money allows you to store wealth and trade it with others.

I believe everybody can be wealthy. Everybody!

It’s not a zero-sum game, it is a positive-sum game.

You create something brand new [and] you exchange it with me for something brand new I’ve created…

[As a result] There’s higher utility for both of us — the sum of the value created is positive…

We should all be playing positive-sum ethical games.

– Naval Ravikant

[Podcast – Joe Rogan Experience #1309 – Naval Ravikant]

Mistaken Belief #2: Most Wealthy People Stole Their Fortune

For most of human history, the fastest way to get rich has been to steal — through direct confiscation or corruption. But now, at least in the Western world where you have a market-based, capitalistic economy, this model has thankfully become mostly outdated…

It was not till the Industrial Revolution that wealth creation definitively replaced corruption as the best way to get rich.

Technology has made it possible to create wealth faster than you could steal it. The prototypical rich man of the nineteenth century was not a courtier but an industrialist.

With the rise of the middle class, wealth stopped being a zero-sum game. Jobs and Wozniak didn’t have to make us poor to make themselves rich. Quite the opposite: They created things that made our lives materially richer. They had to, or we wouldn’t have paid for them.

But since for most of the world’s history the main route to wealth was to steal it, we tend to be suspicious of rich people.

– Paul Graham

[From his Book – Hackers and Painters]

As we can see, the model of becoming wealthy (again, at least in the Western world) has fundamentally changed, but people’s perception of wealth has mostly remained intact!

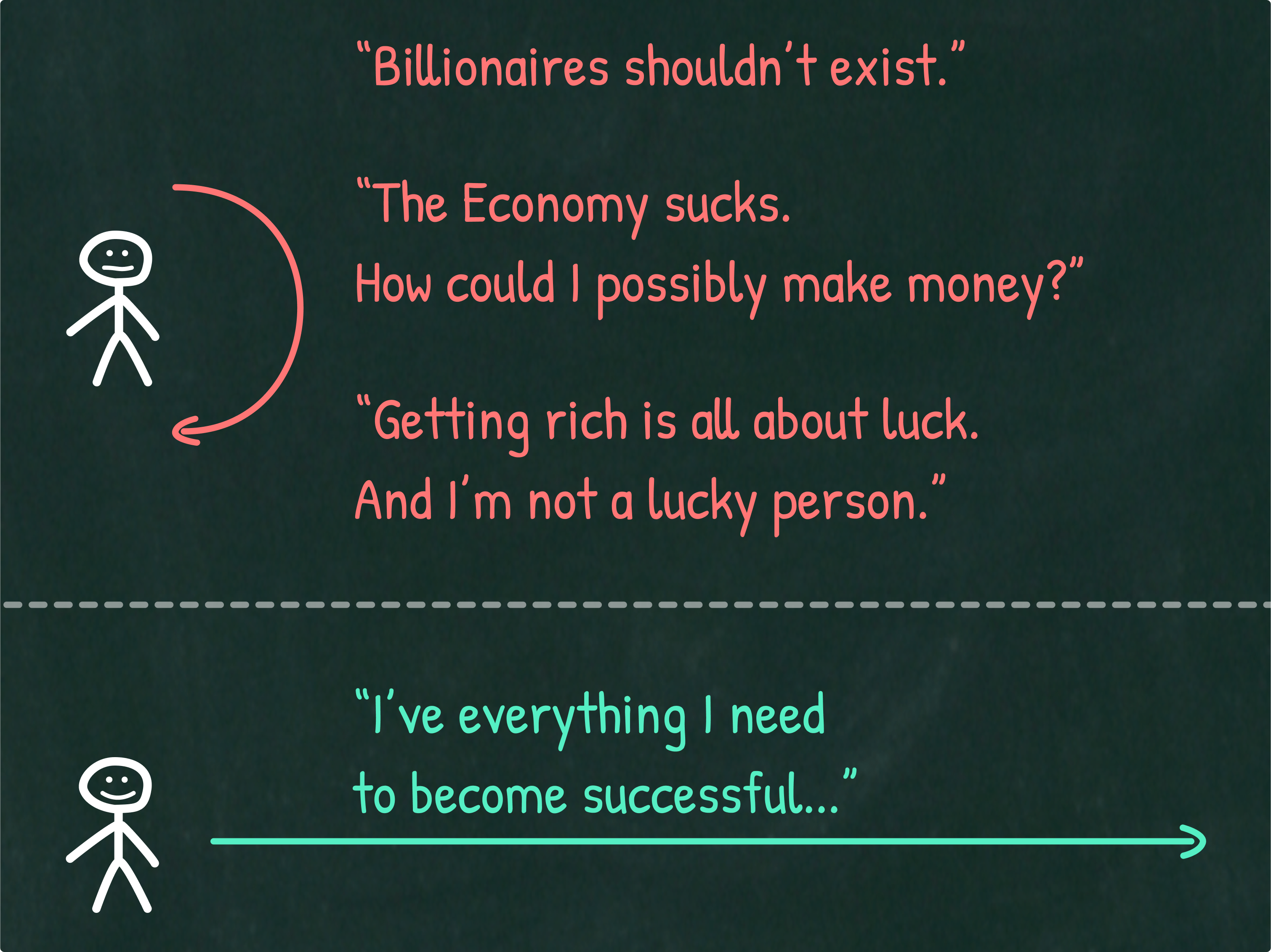

You may wonder: “How can it be that most people still believe in something completely outdated?” Is it just ignorance? And the answer is… ignorance does play a role, but it is not the only thing. There is another key factor in play: The cognitive dissonance produced by one’s current situation and the generalized idea of the financially successful person.

“Cognitive Dissonance” is a psychological phenomenon that occurs when we hold two opposite thoughts in our head. It is extremely uncomfortable for humans, so we tend to keep just one thought (the one that makes us feel better) and get rid of the other thought. And we tend to create any story to justify the thought we keep and another story for why the other thought is completely wrong.

So, the person who isn’t financially successful and wants to be has two choices: (1) He either justifies his current situation and why he can’t change, or (2) he acknowledges that he wants to be financially successful and can be if he puts in the effort and is patient enough to reap the rewards. As we see, these two choices are completely opposite! One tells you that you are okay where you are, and the other tells you that you have agency and the ability to change and improve… But since we have this cognitive dissonance issue, most people have to choose! And guess what most people will pick… Exactly! They will justify their current situation and why it is not possible for them to change — because it’s just much more comfortable to do that! You only need to come up with a compelling (though economically self-defeating) story— which you can probably do in a few minutes (instead of the years of sacrifice that the other choice commands).

But of course, in the long-term it is much better to have chosen the hard path. As the renowned trainer and author Jerzy Gregorek says: “Hard choices, easy life. Easy choices, hard life.”

But of course, in the long-term it is much better to have chosen the hard path. As the renowned trainer and author Jerzy Gregorek says: “Hard choices, easy life. Easy choices, hard life.”

Once someone picks the easy choice, changing his mind is very difficult. He molds his worldview on it, and the confirmation and consistency bias will keep him there for all his life. As Warren Buffet said: “Chains of habit are too light to be felt, until they are too heavy to be broken.” And any time that person sees anything related to high income, wealth, or rich people, his confirmation bias will find any story for why that is wrong! So, of course most people will hold or pick the belief that there is something unfair with the economic system, as it gives them a perfect justification for why they themselves are not wealthy, and why wealthy people are probably evil or at least scrupulous.

Now, what’s the thing that’s left when someone convinces himself that he doesn’t want to become wealthy and yet he sees peers who are better off financially? That thing is called envy…

With all this enormous increase in living standards, freedom, diminishment of racial inequities, and all the huge progress that has come, people are less happy about the state of affairs than they were when things were way tougher.

That has a very simple explanation. The world is not driven by greed; it’s driven by envy.

So the fact that everybody’s five times better off than they used to be, they take that for granted. All they think about is somebody else having more now and it’s not fair that he should have it and they don’t. That’s the reason that God came down and told Moses that he couldn’t envy his neighbor’s wife or even his donkey. I mean, even the old Jews were having trouble with envy. So it’s built into the nature of things. It’s weird for somebody at my age because I was in the middle of the Great Depression and the hardship was unbelievable. I was safer walking around Omaha in the evening than I am in my own neighborhood in Los Angeles after all this great wealth and so forth.

So, and I have no way of doing anything about it. I can’t change the fact that a lot of people are very unhappy and feel very abused after everything’s improved by about 600% because there’s still somebody else who has more.

I have conquered envy in my own life. I don’t envy anybody. I don’t give a damn what somebody else has. But other people are going crazy by it. And other people play to the envy in order to advance their own political careers. We have whole networks now that want to pour gasoline on the flames of envy. I like the religion of the old Jews. I like the people who were against envy, not the people who were trying to profit from it.

Think of the pretentious expenditures of the rich. Who in the hell needs a Rolex watch so you can get mugged for it? Yet, everybody wants to have a pretentious expenditure. That helps drive demand in our modern capitalist society. My advice to the young people is: don’t go there. To hell with the pretentious expenditure. I don’t think there’s much happiness in it. But it does drive the civilization we actually have. And it drives the dissatisfaction.

Steven Pinker of Harvard is a smart academic. He constantly points out that everything’s gotten way, way better, but the general feeling about how fair it is has gotten way more hostile. As it gets better and better, people are less and less satisfied. That is weird, but that’s what’s happened.

– Charlie Munger

[Interview – Charlie Munger speaks at the Daily Journal Annual Meeting]

Of course, there are always some folks who are not wealthy themselves and yet are intellectually honest enough to acknowledge that wealth is positive-sum, who are okay with income or wealth inequality as part of the “economic game of life” in a market-based, capitalist economy and who are not seeking to become wealthy themselves. But this is left to the natural philosophers — people who can think clearly, who know what they really want out of life and have overcome their own cognitive dissonance when it comes to wealth.

The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function. One should, for example, be able to see that things are hopeless yet be determined to make them otherwise.

– F. Scott Fitzgerald (American novelist, essayist, and short story writer)

How many of these natural philosophers do you know? And are you one of them?

Mistaken Belief #3: Income or Wealth Inequality Is Inherently Bad

The third reason why most people treat the skill of making money differently than other skills is the belief that somehow “income inequality” (differences in income from wages, interests, dividends, rent, etc.) or “wealth inequality” (differences in net worth) is bad. This also stems from the mindset of wealth being a zero-sum game, something fixed to be distributed rather than something that can be generated.

The Lever of Technology

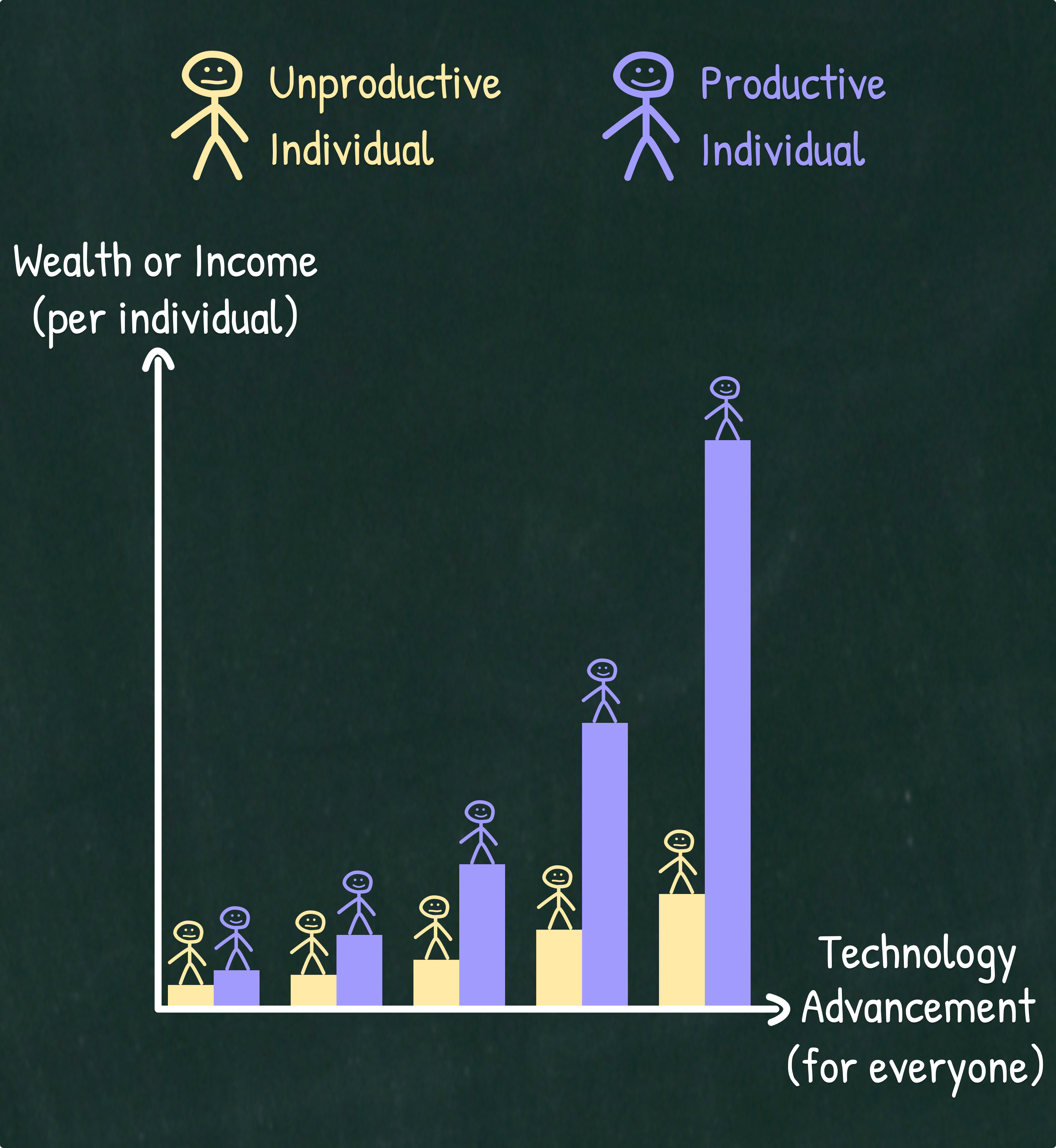

Paul Graham argues that, in a functional free market (where people get rich creating value for others, not through grift), income inequality is actually a sign of a healthy system. Because as new technology is created, it increases the gap between the unproductive and productive people. Paul Graham poses the example: “With a tractor an energetic farmer could plow six times as much land in a day as he could with a team of horses. But only if he mastered a new kind of farming.”

As individual productivity rises, the amount of consensus needed to build something falls. Today a few people (or even just one) can prove a crazy idea works.

Increased productivity leads directly to increased individual independence. Higher productivity means smaller groups. Smaller groups means less averaging. Less averaging means higher variation in outcomes.

– Balaji Srinivasen (Co-founder of Counsyl, former CTO of Coinbase, former General Partner at the VC firm Andreessen Horowitz)

[From the book – The Anthology of Balaji]

In my little group chat — with my tech CEO friends — there is this betting pool for the first year that there’s a one person billion dollar company. Which would’ve been unimaginable without AI… and now it will happen.

– Sam Altman (Co-founder and CEO of OpenAI)

[Interview – Alexis Ohanian interview with Sam Altman]

So, as technology advances, the productive people can produce exponentially more output (per unit of input—e.g./ hour of work) compared to the unproductive, which ultimately increases the income or wealth gap. To say this another way, technology accretes whereas history repeats.

As we see, there’s nothing inherently wrong with income or wealth inequality (even at extreme levels), so far as it is a byproduct of a functional free market.

The Lifestyle Gap

Paradoxically, the advancement of technology also decreases the gap in lifestyle among people! How can something that increases the income or wealth gap also be responsible for decreasing the lifestyle gap? The answer is very simple: Technology democratizes consumption. A billionaire will watch the same TV series, use the same smart phone and computer, and even the same watch and car — that is, if he’s not into ostentatious items.

And this actually further exacerbates the envy issue! Because the more “normal” the wealthy people look (think Zuckerberg in his Adidas flip flops), the more it looks like there are no real differences between them and any other person — which makes a lot of people feel uncomfortable about their current level of wealth. As the joke goes:

Bill Gates and I walk into the bar…

Bartender: “Wow… a couple of billionaires on average!”

Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, and other billionaires might watch the same Netflix series as you and I. Unfortunately, that doesn’t mean we’re at the same level of wealth nor will we be.

By the way, the emotion of envy, when properly cultivated as Nietzsche described, can be used to indicate what you really want and haven’t (yet) obtained — instead of what you resent. When you feel envy you can use it in a productive way by giving yourself the energy to self-actualize and focus on what you secretly really want. Why? Because when used properly our emotions are a clue to help guide our actions, and the emotion of envy is not an exception. Renowned value investor, Guy Spier, said it best in an interview with Stig Brodersen:

The emotion of envy says: “That person has something that I deserve to have in my life.” I don’t think that we feel the emotion of envy for something that is unreachable. I don’t think that the people who come into the presence of the Queen or people who come into the presence of Ronaldinho (or another soccer player) feel envy… Because the skills are just so great and they’re so unattainable [that] you feel awe. You feel awe to be in their presence.

Now, [Novak] Djokovic might feel envy for [Roger] Federer. Why? Because he knows he has the capacity for the greatness that Federer has.

Now, if you take the Djokovic-Federer rivalry, what does Djokovic do with that envy?

If he does what the ice-skating woman did — she went and sabotaged her rival Nancy Kerrigan — that is a terrible misdirection of the emotion of envy. But the emotion that says: “Wow. I’m feeling this envy actually because I’m a genuine rival to this person and I need to go to work on maybe making that a reality.” I think that is a very useful use of envy.

Assortative Mating

On top of the technology factor as a driver of income and wealth inequality, there is another factor that is worth mentioning. And that is the “assortative mating” phenomenon. Tyler Cowen said it best in his book The Complacent Class: The Self-Defeating Quest for the American Dream:

“Assortative mating” — that is, the marriage of people of similar educational and socioeconomic backgrounds — has become more widespread than in the past. That phrase refers to matching generally, but it also refers more specifically to men of high education and income marrying women of high education and income. More concretely, lawyers marry other law partners, or perhaps investment bankers, rather than their secretaries.

This in turn propagates inequality across the generations, as the money and brains become clustered in high-powered, two-earner families, determined to do everything possible to advance the interests of their children and endowed with the skills to see that commitment through.

One study showed that family-connected decisions, including marriage, choice of spouse, female labor supply, and lower divorce rates for wealthier couples, accounted for a third of the rise in income inequality from 1960 to 2005. In other words, if you wish to understand income inequality, or for that matter the American economy, don’t just study the New York Times business section; turn also to the Sunday marriage pages.

Assortative mating helps exacerbate inequalities of opportunity. And that’s okay because the opposite — forcing people to marry people they don’t want to — is tyrannical.

Final Thoughts

We will only be able to see the “money game” as meritocratic as sports or other competitive games when, in a free market economy, the state guarantees that everyone has a shot to advance in life — although not the same shot — and we also make an effort to:

1. Abandon the erroneous belief that wealth is zero-sum (ironically, sports are completely zero-sum games — to win someone else has to lose).

2. Avoid letting our cognitive dissonance distort our perception of reality, and realize that just because other people have more than us wealth-wise does not mean that it makes us poorer or somehow limits our ability to self-actualize.

3. Realize that income and wealth inequality are signs of a healthy system — provided it is the byproduct of actual wealth creation (which is true at least in the Western world).

Key Takeaways – Inequality vs. Unfairness

- Inequality and unfairness are not the same thing, but there is one kind of inequality that links to unfairness — and that is inequality in the initial conditions of a game or activity. All other types of inequality have no connection to unfairness.

- We can easily spot the difference in non-economic domains (such as sports, tests, etc.), but it’s hard to see it in the economic context. The reason for that is:

- The belief that wealth is a zero-sum game (meaning that for someone to get rich there has to be another person/s who loses). Although it’s an undeniable fact that wealth creation is a positive sum-game (everyone gets wealthier, on an absolute scale).

- The way that fortunes have been accumulated up until the start of the Industrial Revolution — through confiscation or corruption. This is no longer true, as the most common way to get rich now is by actually making abundance for society.

- The belief that somehow income or wealth Inequality is inherently wrong, although it’s been shown empirically that this is not true.

- The role of the state in ensuring the economic game of life is “equal” is limited to resolving disputes in a timely and consistent manner, enforcing contracts, and upholding the rule of law. Other attempts to “tip the scale” and correct for perceived imbalances in the name of historical grievances (real or imagined) don’t work, have unintended consequences, and/or perpetuate a victim mentality.

If You Liked This Essay, Check Out These Sources

- The Black Swan, by Nassim Nicholas Taleb.

- Hackers and Painters, by Paul Graham.

- Podcast – Joe Rogan Experience #1309 – Naval Ravikant

- Blogpost – What Nietzsche Would Say About Instagram

- Interview – Charlie Munger speaks at the Daily Journal Annual Meeting

- Interview – Guy Spier Conversation with Stig Brodersen

- The Anthology of Balaji, by Eric Jorgenson.

- Interview – Alexis Ohanian interview with Sam Altman

- The Complacent Class: The Self-Defeating Quest for the American Dream, by Tyler Cowen.

Free Market Quotes That Show Why Freedom Fuels Growth

Love it or hate it, the free market has lifted millions from poverty and fueled innovation. But what makes it so indispensable? These voices weigh in. While one can debate…