Table of Contents

In June of 1996, Steve Jobs gave a speech at the Palo Alto High School graduation where he shared the following insight:

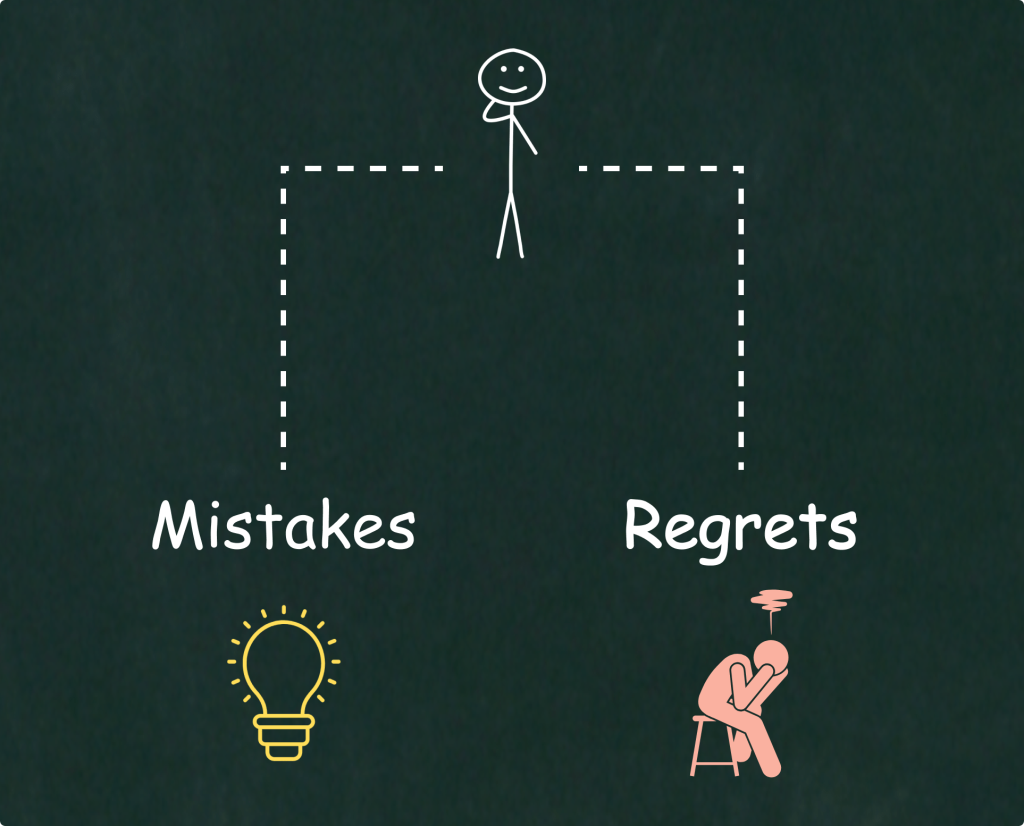

Regrets are different from mistakes. Mistakes are those things that you did and wish you could do over again. In some you were a fool (usually concerning women). In others you were scared. In others you hurt someone else. Some mistakes are deep, others not. But if your intent was pure, they are almost always enriching in some way. So mistakes are things that you did and wish you could do over again.

Regrets are most often things you didn’t do, and wish you did. I still regret not kissing Nancy Kinniman in high school. Who knows what might have happened? Maybe she regrets it too…

– Steve Jobs

[Book – Make Something Wonderful]

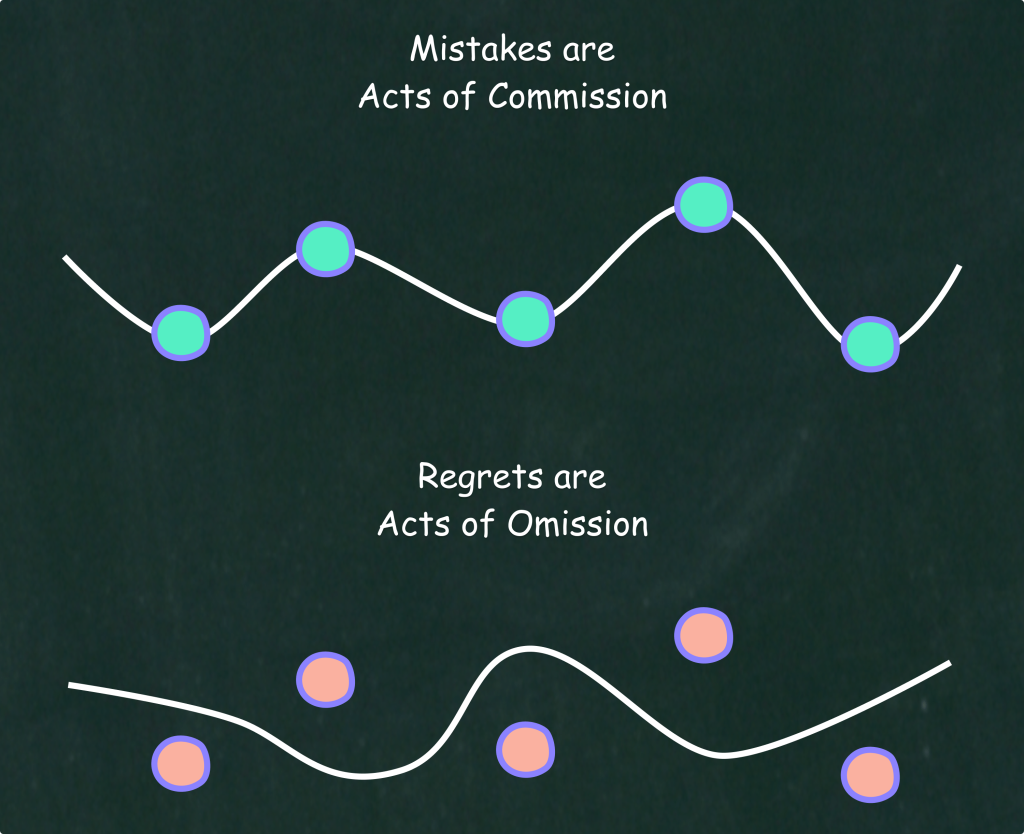

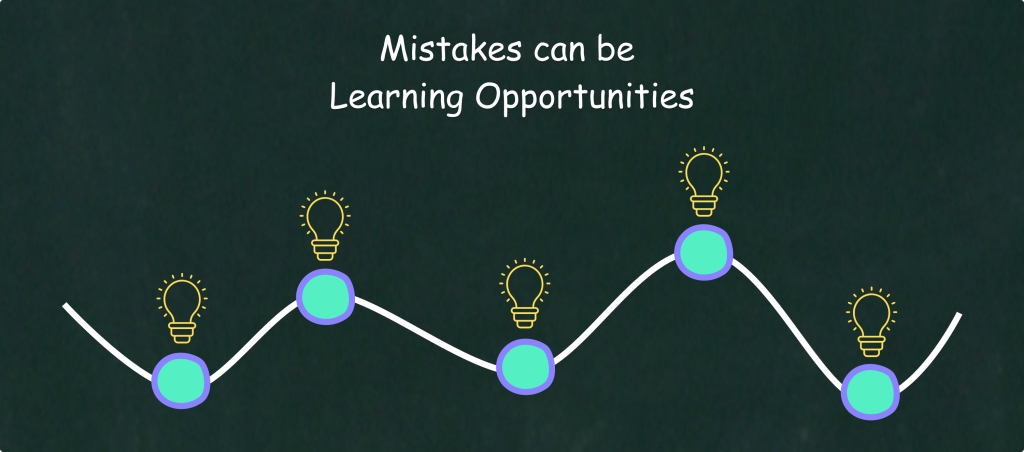

Generally speaking, mistakes are acts of commission as opposed to omission, and they can serve as learning opportunities to fuel your personal growth. And I say “can serve as learning opportunities” because you still have to put in the effort to reflect and learn from your mistakes. Doing so is challenging for reasons we’ll get into below. Not putting in the effort to learn from your mistakes is worse, however, because by not doing so, you are setting yourself up to repeat mistakes of a similar nature over and over.

Forgetting your mistakes is a terrible error if you are trying to improve your cognition.

– Charlie Munger (Ex-Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway)

It’s only when you are not willing to learn from your mistakes that those mistakes can lead to regret.

What’s the difference between a mistake and a regret?

I would argue a regret is simply a mistake that we haven’t learned the proper lesson from yet. Often, we regret because we did something so cataclysmic that it’s difficult to learn the appropriate lesson. But often, we regret not because our actions were so heinous, but simply because we lack the imagination to pull something productive out of them.

– Mark Manson (Author of the best-seller book The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck)

[From his blog post – “How to Deal with Regret”]

Thus, if you have a genuine willingness to learn from your mistakes and you actually do, then you can only have regrets from acts of omission — those things you wish you did but never took action on. And there are two techniques that can significantly minimize the number of omission-based regrets. Before going there, let’s dive a bit deeper into the topic of mistakes to make sure we’re talking about the same thing.

Using Mistakes as Learning Opportunities

How Successful People Generally Regard Their Mistakes

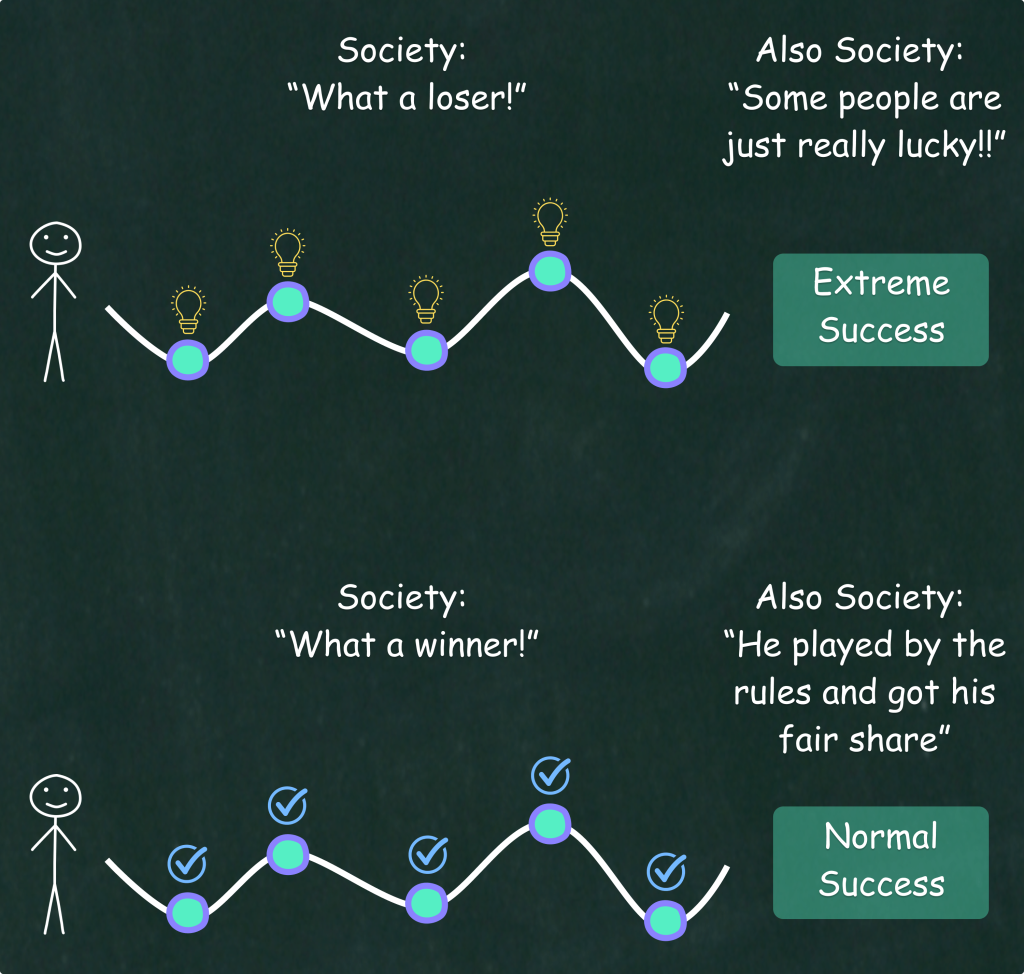

As we saw earlier, a mistake can be a blessing in disguise if we see it as a learning opportunity and actually learn from it. What’s weird here is the following societal phenomenon: Individuals who make too many mistakes, over and over, are shunned, and yet the really successful people in the world also make mistakes — they just understand that mistakes do, in fact, provide excellent learning opportunities, and they learn from them!

To build better judgment, learn as much as you can from each of your mistakes. Doing so should help you make fewer of mistakes of a similar nature in the future. This is how you build better judgment about yourself and others.

So, although it might sound counterintuitive on the surface, one way to make fewer mistakes (i.e., to develop good judgment with a low error rate) is to be willing to make a lot of mistakes and learn from them quickly. As Jeff Bezos also says, it’s critical to have a “willingness to fail” (when you experiment) in order to succeed later.

(The other way is to learn from other people’s mistakes — which is even better because you don’t have to pay the price of the mistake — but we will dive into this topic in a later chapter. )

On The Lex Fridman Podcast, renowned entrepreneur and venture capitalist Chamath Palihapitiya explained this idea perfectly:

In terms of your mistakes… Society tells you: “don’t make them.” Because we will judge you and we will look down on you. And I think the really successful people realize that actually no… it’s the cycle time of mistakes that gets you to success! Because your error rate will diminish: The more mistakes that you make (you observe them, you figure out where it’s coming from… Is it a psychological thing? Is it a cognitive thing?) and then you fix it!

[The word] “Mistake” is maybe a bad proxy but it’s the best proxy I have for learning. But I’m using the language of what society tells you. Society tells you that when you try something and it doesn’t work it’s a mistake. So I just use that word because it’s the word that resonates [the] most with most people. [But] The real thing that it is… is learning!

I think mistakes scare people because society likes these very simplified boundaries of who is winning and who is losing. And they want to reward people who make traditional choices and succeed. But the thing is… What’s so corrosive about that, is that they’re actually not even being put in a position to actually make a “mistake” and fail.

Set an Audacious Goal

As Chamath points out, it’s all about how quickly you can make mistakes AND learn from them that sets you up for the fastest route to success. You want to fail fast, small, and often when you are learning something because that indicates you’re at the edge of what you already know.

A great way to encourage many manageable mistakes is to have a goal that stretches your capabilities, where the probability of failure is significant but won’t be cataclysmic.

As Chamath also pointed out, you need to put yourself in a position to actually make a “mistake” and fail! Otherwise, you are not being ambitious enough about your own personal development. You also need to make sure you don’t die, as some mistakes can kill you.

The Philosopher’s Stone for Progress

One important caveat to the process of making mistakes is that these mistakes have to be inconsequential, or at least not so consequential that they can kill you (e.g., losing all your money in one investment or, even worse, losing your life). In order to make many mistakes and eventually improve your judgment, you first need to survive!

Having an “edge” and surviving are two different things: The first requires the second. As Warren Buffet said: “In order to succeed you must first survive.” You need to avoid ruin. At all costs.

– Ed Thorp (Mathematician, author, hedge fund manager, and blackjack researcher known for discovering the mathematics of card counting and other casino successes)

[From his book – A Man for All Markets]

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, author of the best-seller The Black Swan, argues that this process of making frequent inconsequential mistakes (also called “trial and error”) is the real Philosopher’s Stone to unleash invention and progress.

To outperform trial and error intellectually… You need (at least) a thousand IQ points.

– Nassim Nicholas Taleb

We have the illusion that the world functions thanks to programmed design, university research, and bureaucratic funding, but there is compelling — very compelling — evidence to show that this is an illusion, the illusion I call lecturing birds how to fly. Technology is the result of anti-fragility [things that thrive in randomness and uncertainty], exploited by risk-takers in the form of tinkering and trial and error, with nerd-driven design confined to the backstage. Engineers and tinkerers develop things while history books are written by academics; we will have to refine historical interpretations of growth, innovation, and many such things.

– Nassim Nicholas Taleb

[From his book – Antifragile]

Mistakes as Bruises: The Privilege of the Active

On top of the learning opportunity, I think it’s a great motivator to think of mistakes as the bruises one acquires; they’re the privilege of the active.

It is “the man in the arena” who will make mistakes and, consequently, he sets himself (or herself) up to be the most glorious and adventurous of all!

Only while sleeping one makes no mistakes. Making mistakes is the privilege of the active — of those who can correct their mistakes and put them right.

– Ingvar Kamprad (Founder of Ikea)

Charlie Munger: Learn from Other People’s Mistakes

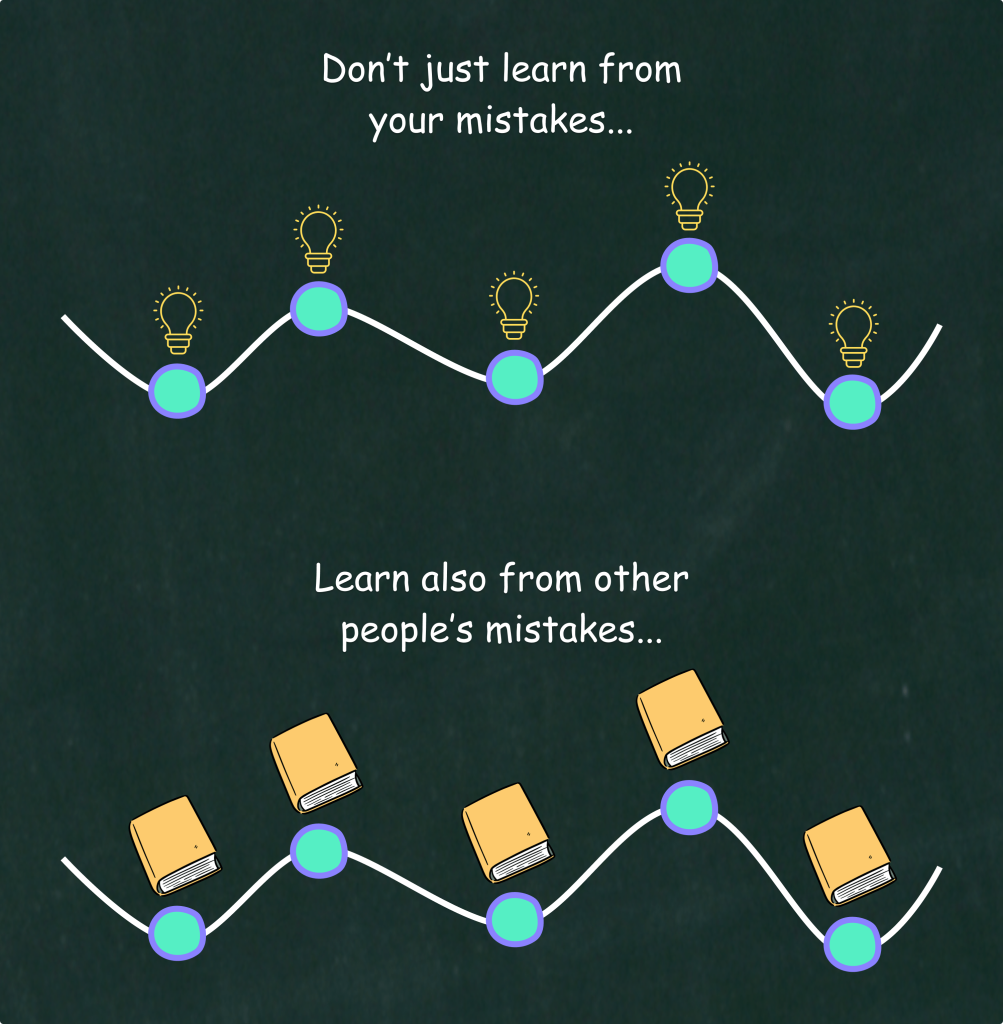

A great hack to accelerate your cycle time of mistakes, without even having to make the mistakes yourself, is to learn from other people’s mistakes. They’ll often tell you what not to do!

As Charlie Munger would say, become a voracious reader in order to learn and absorb as much as possible from the experience of others, especially historically significant figures who have left a lasting impact on the world.

You’ve heard that old chestnut from Sir Isaac Newton, “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulder of giants.”, right? It is in a similar vein: You’re able to make new discoveries and gain new insights because of the foundational work of those who came before. And the best way to know about those who came before is to read what they wrote down.

It’s good to learn from your mistakes.

It’s better to learn from other people’s mistakes.

– Warren Buffet

My prescription for misery is to learn everything you possibly can from your own experience, minimizing what you learn vicariously from the good and bad experiences of others, living and dead. This prescription is a sure-shot producer of misery and second-rate achievement.

– Charlie Munger

[From the book – Poor Charlie’s Almanack: The Essential Wit and Wisdom of Charles T. Munger]

Learning from mistakes, other people’s mistakes, is the best way to learn. Why learn from your own mistakes? You know, why learn from your own embarrassment? You got to learn from other people’s embarrassment. That’s why we have case studies, and isn’t that right? We’re trying to read from other people’s disasters, other people’s tragedies. Nothing makes us happier than that.

– Jensen Huang (Founder of Nvidia)

Regrets: Acts of Omission, Not Commission

As stated earlier, if we have a willingness to learn from our mistakes (and we exclude obvious instances of wrongdoing such as criminal acts), the only kind of regrets we can have stem from acts of omission (not doing something) as opposed to commission (doing something).

Most regrets are acts of omission and not commission. I think most people when they’re 80 years old—[exception]: you can do bad things, you can go murder somebody and that would be bad and that would be an act of commission that you would regret—but for most people (everyday ordinary non-murderers) their big regrets are omissions!

– Jeff Bezos

So, starting from this basis, the question becomes, “How can I eliminate or minimize the number of omission-based regrets?”

Of course, it’s hard to get rid of regrets completely, but there are two techniques that can help us significantly minimize the number of omission-based regrets.

The first technique is inspired by Jeff Bezos, while the second one is by the renowned comedian Jerry Seinfeld.

Jeff Bezos: “The Regret Minimization Framework”

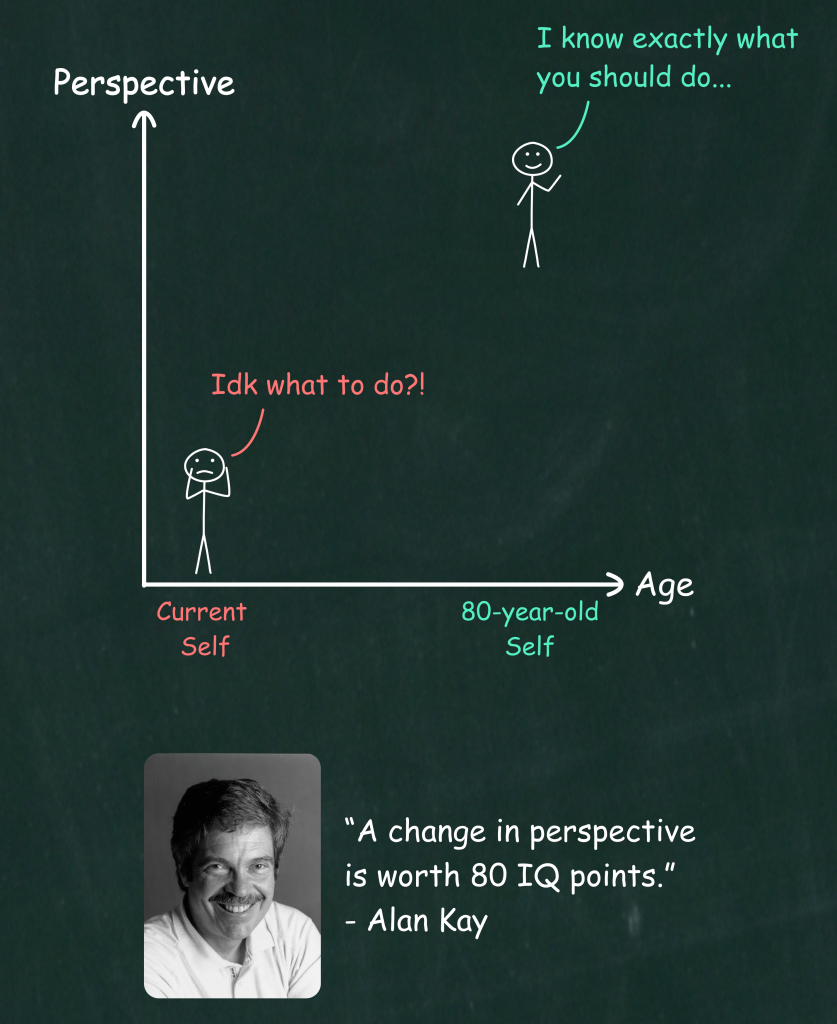

The technique is quite simple. Whenever you have doubts about an important issue, you project yourself to age 80 or 90, and then you think about the issue. Many times, with the advantage of the perspective old age affords you, the best decision (the one that minimizes regrets) will look obvious.

In an interview in 2001, Jeff Bezos explained how he came up with this technique and used it to quit his job and start Amazon:

I went to my boss and said to him: “you know I’m gonna go do this crazy thing, and I’m gonna start this company selling books online.”

And this is something that I’ve already been talking to him about — in a sort of more general context — but then he said: “let’s go on a walk.”

And we went on a two-hour walk in Central Park in New York City.

And the conclusion of that was… he said: “You know, this actually sounds like a really good idea to me. But it sounds like it would be a better idea for somebody who didn’t already have a good job.”

[Jeff laughs]

And he convinced me to think about it for 48 hours before making a final decision.

And so, I went away and I was trying to find the right framework in which to make that kind of big decision.

And I already talked to my wife about this and she was very supportive and said: “Look, you can count me in 100% whatever you want to do.” It’s true she had married this kind of fairly stable guy in a stable career path and now he wanted to go do this crazy thing… but she was 100% supportive.

So it really was a decision that I had to make for myself.

And the framework I found, which made the decision incredibly easy, was what I call (or only a nerd would call): “A regret minimization framework.”

So, I wanted to project myself forward to age 80. And say: “Okay, now I’m looking back on my life… I want to have minimized the number of regrets I have.”

And what I knew [was] that when I was 80 I was not going to regret having tried this. I was not gonna regret having tried to participate in this thing called “the Internet” — that I thought was gonna be a really big deal. I knew that if I failed I wouldn’t regret that.

But I knew the one thing I might regret is not ever having tried — and I knew that that would haunt me every day.

And so when I thought about it that way, it was an incredibly easy decision!

If you can project yourself out to age 80 and sort of think: “What will I think at that time.” It gets you away from some of the daily pieces of confusion. You know, I left this Wall Street firm in the middle of the year, [and] when you do that you walk away from your annual bonus. And that’s the kind of thing that in the short-term can confuse you, but if you think about the long-term then you can really make good life decisions that you won’t regret later.

– Jeff Bezos

Jerry Seinfeld: “The Clear Mind”

Many times, we have regrets that stem from a lack of reflection or understanding of reality.

Take, for instance, the people at the end of their lives who tend to say that they regret having worked so much. Implicit in that statement is a deep-seated assumption that work matters only to the extent that it makes money. And thus, if they worked too much, it meant that they got “greedy” and traded too much of their time for money.

But I would make the case that this regret has little to do with having worked too much and more with having chosen a career path that didn’t align with the genuine interests and values of that individual.

Thus, in this particular example, the problem stems from the common but devastating assumption that the purpose of work is to just “make a living” or to gain social status if you are successful in “climbing up the ladder.”

The renowned comedian Jerry Seinfeld addressed this issue on his Commencement Speech at Duke University:

About work, you know how they always say: “Nobody ever looks back on their life and wishes they spent more time at the office?”

Well, why?

Why don’t they?

Guess what?

Depends on the job!

If you took a stupid job that you find out you hate and you don’t leave, that’s your fault.

Don’t blame work.

Work is wonderful.

I definitely will not be looking back on my life wishing I worked less.

If that’s not how you feel at work… Quit! On your lunch break… Disappear! Make people go “What happened to that guy?,” “I don’t know, he said he was getting something to eat. Never came back.”

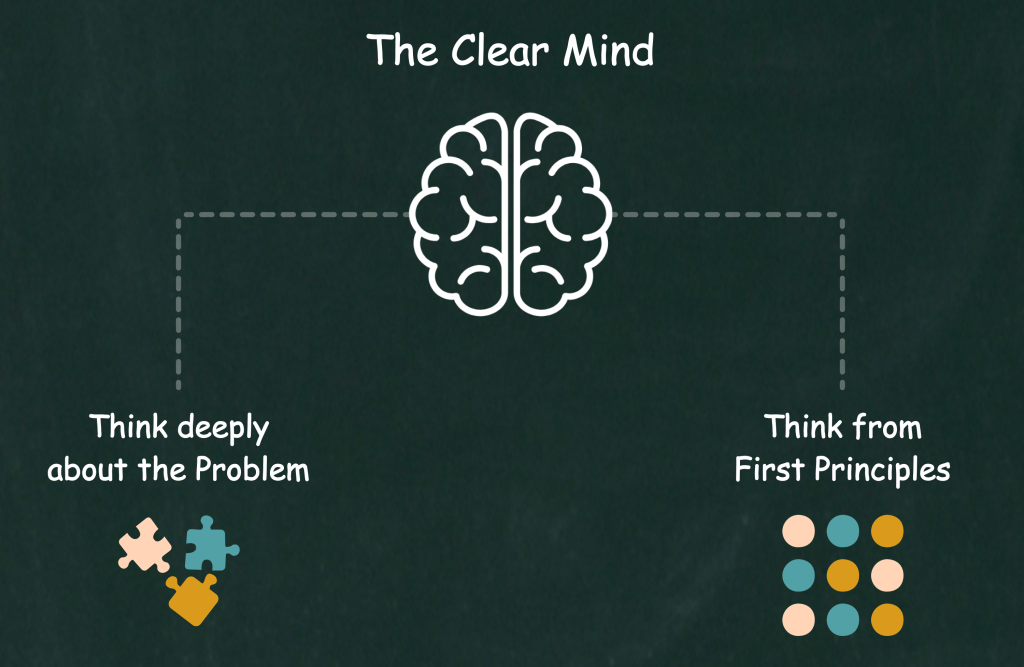

The lesson here is not so much about this particular instance but the meta-lesson behind it:

1. First, reflect deeply on the problem and take adequate time to consider it. As Albert Einstein famously said: “If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and five minutes thinking about solutions.”

2. Second, be careful when making assumptions. At least for the important things in life, we should always take the time to think from first principles rather than by analogy or mindlessly copying what other people are doing. To think from first principles, you have to question your assumptions and deconstruct them into the smallest pieces which we know are true, and then reason up from there and form a unique conclusion.

All error springs from flawed assumptions. If there are no assumptions, there can be no error.

I am told that during the Vietnam War, a sign was kept nailed on a wall above a particular marine commander’s desk which said: ‘Assumption is the mother of all f***-ups’.

– Felix Dennis (British publisher, poet, and philanthropist. Founder of Dennis Publishing)

[From his book – How to Get Rich]

Don’t be a follower… Be a student!

Take advice but not orders, take information but don’t let somebody order your life.

Make sure what you do is the product of your own conclusion.

– Jim Rohn (Entrepreneur and Renowned Motivational Speaker)

Summary Guide

Generally speaking, mistakes are acts of commission which, when properly utilized, can be excellent learning opportunities if the mistakes are manageable. (You don’t want to die.)

One way to ensure that you make enough manageable mistakes is to set an audacious goal — where the probability of success is small (but the probability of personal growth is large). Something that stretches you without killing you, let’s say.

Thus, make sure that these mistakes aren’t so consequential that they can “get you out of the game” (a.k.a. never risk survival). And make it a habit to learn from “other people’s tragedies” as opposed to your own; they’re less costly that way.

Regrets are very often acts of omission — those things you wish you did but never did. And there are two ways to minimize your number of (omission-based) regrets:

1. Adopt the “Regret Minimization Framework” from Jeff Bezos, where you project yourself out to age 80 or 90 and make the decision from that viewpoint.

2. Cultivate a “Clear Mind” as explained by Jerry Seinfeld. You can do this by reflecting deeply on the problem and thinking from first principles (rather than mindlessly copying what other people are doing).

If You Liked This Essay, Check Out These Sources

- Make Something Wonderful, by Steve Jobs

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck, by Mark Manson

- Mark Manson on How to Deal with Regret

- Chamath Palihapitiya on Mistakes

- A Man for All Markets, by Ed Thorp

- The Black Swan, by Nassim Nicholas Taleb

- Nassim Nicholas Taleb on Trial and Error

- Antifragile, by Nassim Nicholas Taleb

- Poor Charlie’s Almanack: The Essential Wit and Wisdom of Charles T. Munger, edited by Peter Kaufman

- Jensen Huang on learning from other people’s mistakes

- Jeff Bezos on Regrets

- Jeff Bezos on The Regret Minimization Framework

- Jerry Seinfeld on the Truth about Work

- How to Get Rich, by Felix Dennis

- Jim Rohn’s 4 hour Seminar

Pain vs. Suffering: The Seed Of Your Life Story

The single best explanation I’ve come across on the difference between pain and suffering comes from a talk that Yen Liow gave at Columbia Business School. The fundamental premise is…