Table of Contents

Do you know the phrase “to be overcome by emotion” when describing or justifying one’s actions, post-haste?

What if you didn’t have to be overcome by emotion? And instead could use your emotions as internal guideposts to help you calibrate for what you really want – and then act accordingly, from a place of poise and power?

That’s both the promise and peril of emotions. True self-mastery comes from being highly attuned to your emotions as indicators of what you desire without being overcome by them. And then developing the capacity to reason through your next steps and to take action in accordance with those desires.

It’s not the absence of desire that we all want. It’s the fulfillment of certain desires, assuming we’re comfortable with the trade-offs necessary to achieve them.

Taking a lot of drugs on a regular basis might make you feel great in the short-term. After all, that’s emotionally what you want – to feel great. But the long-term consequences might not be worth the trade-offs to your health, wealth, and relationships.

Jim Rohn said it well:

Here’s what’s exciting about each person’s personal philosophy.

That’s what makes us different than dogs and animals, birds and cats, and spiders and alligators.

That’s what makes us different than all other life forms. The ability to think, the ability to use your mind, the ability to process ideas, and not just operate by instinct.

In the winter, I’m telling you, the goose can only fly south.

What if south doesn’t look too good?

Tough luck.

It can only fly south.

But see, human beings are not like a goose who can only fly south.

I mean, you could turn around, go north, you can go east, you can go west, you can order the entire process of your own life.

And we do that, by the way we think. We do that by exercising our mind. We do that by processing ideas, and come up with a better philosophy, a better strategy for our life, goals for the future.

You may be wondering: Isn’t it better to try being completely rational? And to answer this question, I want to first set the scene with a quote from Dee Hock (founder of Visa) and the renowned psychiatrist Carl Jung.

Education that gives priority to measurement rather than values, to efficiency rather than conscience, to information rather than ethics, provides no barrier to barbarity and violence. The Holocaust was perpetrated by a society of the most disciplined, highly educated people on earth.

– Dee Hock (Founder of Visa)

An ancient adept has said: ‘If the wrong man uses the right means, the right means work in the wrong way.’ This Chinese saying, unfortunately all too true, stands in sharp contrast to our belief in the ‘right’ method irrespective of the man who applies it. In reality, in such matters everything depends on the man and little or nothing on the method. For the method is merely the path, the direction taken by a man. The way he acts is the true expression of his nature. If it ceases to be this, then the method is nothing more than an affectation, something artificially added, rootless and sapless, serving only the illegitimate goal of self-deception. It becomes a means of fooling oneself and of evading what may perhaps be the implacable law of one’s being.

– Carl Jung

[From his book – Alchemical Studies]

You see, science, and the tools it produces, are never ends in themselves; they always have to be means to an end. And that end has to be guided by the feelings, taste, and wisdom of each human being.

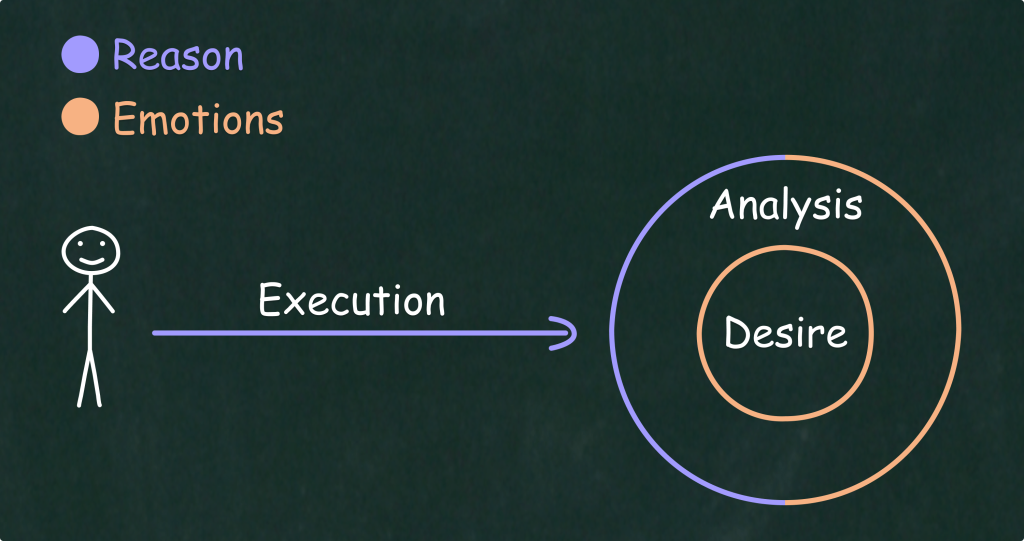

Therefore, we have to embrace our emotions and feelings — rather than try to erase them. And after we embrace them, we go through a careful analytical process to decide if it’s actually a good decision or not, and how to achieve it.

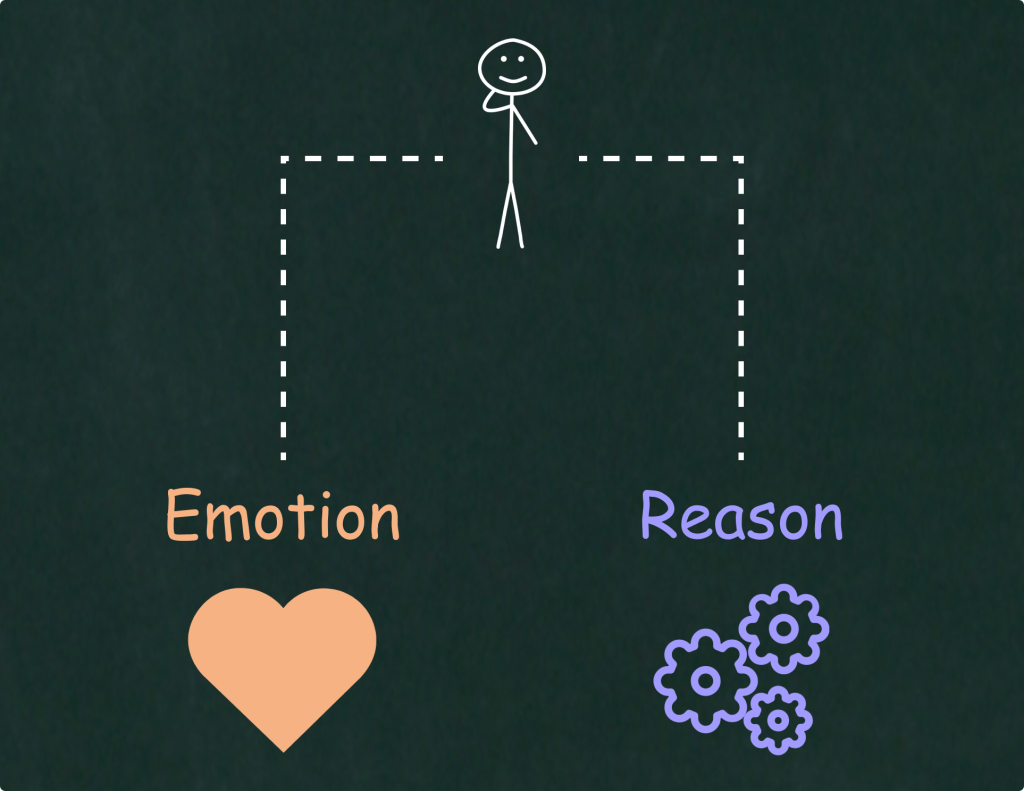

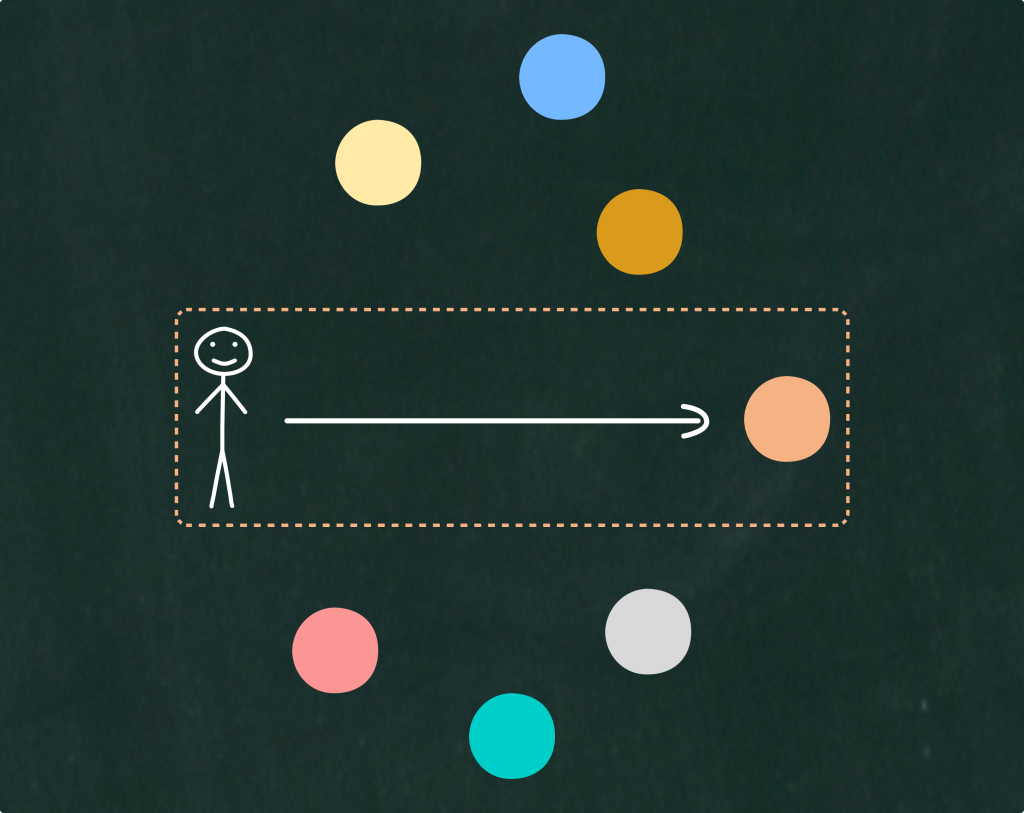

So, it’s not good to be either purely emotional or purely rational. We need to learn how to integrate both together — and it follows this process:

- Decide what you want (using your emotions as cues),

- Analyze it (by cultivating emotional sensitivity and your capacity to reason),

- And then work with reality to get it (using reason).

Now, let’s break down each of the three steps outlined earlier to get a clearer picture of the difference between emotion and reason, and to understand the fundamental basis for achieving what we want in life.

1. Figure Out What You Want (Use Emotion)

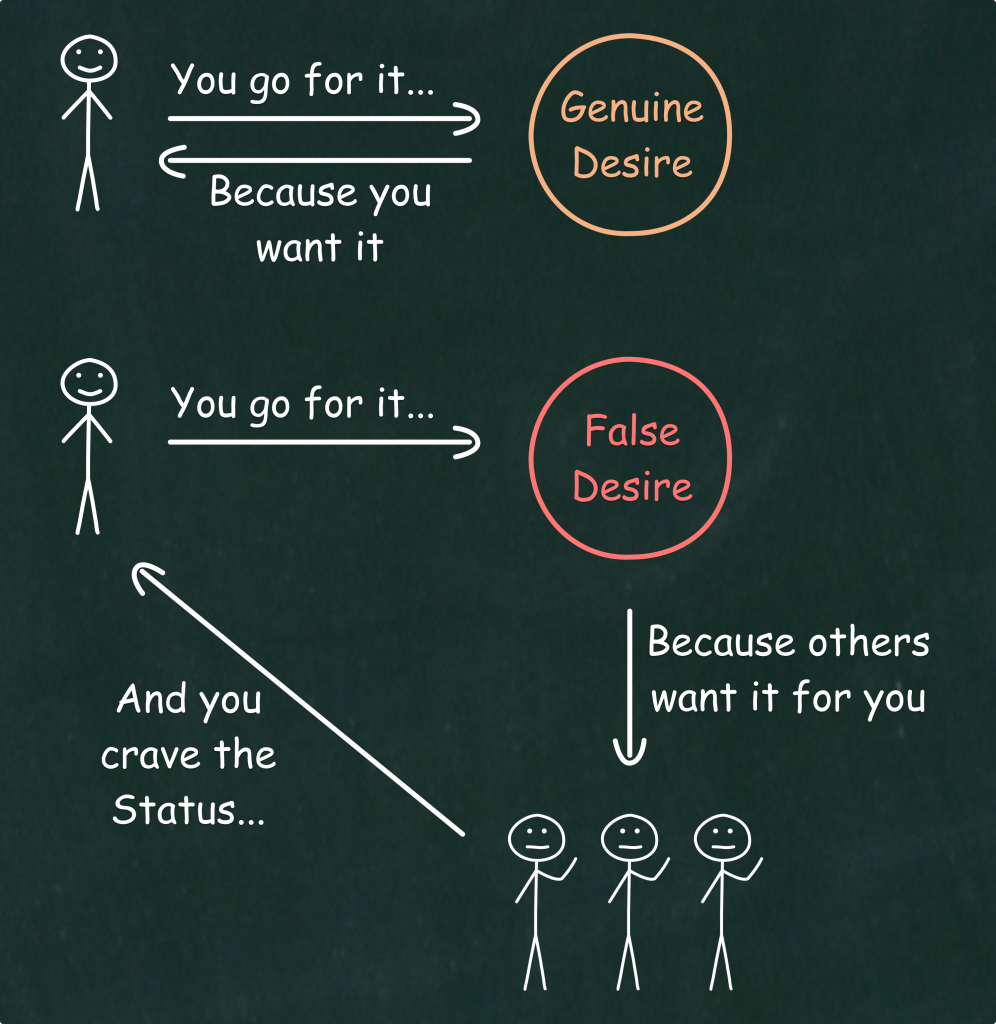

This might seem like an easy thing to do. But what we’re really talking about here is: What do you genuinely want?

And that’s not so easy to figure out, because we’re constantly surrounded by expectations from others about what we should want. On top of that, we’ve evolved to crave prestige and status.

So it’s a daunting task to strip all that away and figure out whether we truly want something… or if it’s just a way to boost our status and make others happy.

In the words of Warren Buffett:

Would you rather be the world’s greatest lover, but have everyone think you’re the world’s worst lover?

Or would you rather be the world’s worst lover but have everyone think you’re the world’s greatest lover?

Personally, I’d choose the first option. That’s what brings real satisfaction. Also, doing things for the attention of others means that you depend on others to be happy, which is a terrible place to be.

You have no responsibility to live up to what other people think you ought to accomplish. I have no responsibility to be like they expect me to be. It’s their mistake, not my failing.

– Richard Feynman

One of the resolutions I came up with (a number of years ago) was to always value Substance over Status, Substance over Prestige.

And, if I sort of was giving my younger self advice on what to do or how to think about one’s life. I probably would still go to Stanford. I might still go to Law School. But I’d ask a lot more questions… Why I was doing these things.

And I think if I was honest about it, too much of it was driven by prestige and status and not quite enough about really the substance of trying to learn things.

And you know, I sort of think of it as this sort of crazy rolling quarter life crisis and sort of culminated in this big New York Law firm where… from the outside, everybody wanted to get in; from the inside, everybody wanted to get out… I lasted 7 months and 3 days. And when I left, one of the people down the hall said:

“It’s so reassuring to see you leave, Peter. I had no idea it was possible to escape from Alcatraz.”

Which, again, all you had to do was go through the front door… But people’s identities get so wrapped up in the things they compete for that it was inconceivable for people to actually do that.

And then the question was: “Well, how did I end up there? Why had I not thought about that more?

And I think it was that I had taken too many of these shortcuts of valuing what was prestigious, what was conventional, over what I really wanted to do.

So, I think always: Substance over Status.

– Peter Thiel (Co-founder of PayPal and Palantir Technologies)

[Video Source]

To the untrained eye ego-climbing and selfless climbing may appear identical. Both kinds of climbers place one foot in front of the other. Both breathe in and out at the same rate. Both stop when tired. Both go forward when rested. But what a difference!

The ego-climber is like an instrument that’s out of adjustment. He puts his foot down an instant too soon or too late. He’s likely to miss a beautiful passage of sunlight through the trees. He goes on when the sloppiness of his step shows he’s tired. He rests at odd times. He looks up the trail trying to see what’s ahead even when he knows what’s ahead because he just looked a second before. He goes too fast or too slow for the conditions and when he talks his talk is forever about somewhere else, something else. He’s here but he’s not here. He rejects the here, is unhappy with it, wants to be farther up the trail but when he gets there will be just as unhappy because then it will be “here.” What he’s looking for, what he wants, is all around him, but he doesn’t want that because it is all around him. Every step’s an effort, both physically and spiritually, because he imagines his goal to be external and distant.

– Robert Pirsig

[From his book – Zen and The Art of Motorcycle Maintenance]

2. Analysis: Be Careful of What You Want (Use Emotion and Reason)

Analyze Yourself With Emotion and Reason

This is the part where you simply reflect on how realistic your goal is, based on your aptitudes and your “willingness to suffer” for the thing you want.

Do you have an inner compulsion to get it? Or is it just a fleeting desire?

Would you wake up every morning with genuine enthusiasm to pursue it, day after day?

The renowned entrepreneur Felix Dennis explained this beautifully in his book How To Get Rich, using the example of people who want to get rich, though the same logic applies to any desire, not just wealth.

All error springs from flawed assumptions. If there are no assumptions, there can be no error.

I am told that during the Vietnam War, a sign was kept nailed on a wall above a particular marine commander’s desk which said: ‘Assumption is the mother of all f***-ups’. Those seven words should be carved into the heart of every entrepreneur, the wealthy or the wannabe, the gonnabe or the been-there-done-that. A shame they weren’t nailed above the desk of the president of the United States at the time.

As far as getting rich is concerned, the cardinal error is to begin such a quest in the vague belief that you would like to be rich. Wishing or desiring to be rich is perhaps the most commonplace of human desires, other than sexual fantasy. Yet few people ever succeed in achieving it.

Such desire is a fleeting thing, a will-of-the-wisp floating across the surface of the mind as you pass the front window of a chic boutique: ‘I wish I was rich. If only I could afford it, I would march straight inside and buy that beautiful handbag.’ Then the No. 43 bus comes along, and all such thoughts are abandoned on the pavement.

“Wishes are fishes that swim in the nets

Of castaways’ souls by the shores of the dead,

Where coins are as rare as a ferryman’s debts,

And nobody cares what you did, or you said.Wishes come skipping and eager to play

In the ravenous dreams of childless wives;

Wishes are thoroughbreds feasting on hay

While rickety mendicants limp all their lives.”Wishing for or desiring something is futile without an inner compulsion to achieve it. Such lack of compulsion, if not frankly acknowledged, can lead to great personal unhappiness. We have all met deeply unhappy souls muddling along in professions or careers for which they are patently unsuited.

Worse still, by continually wishing and never delivering, you risk denting your confidence, beginning a vicious downward spiral that appears to draw misfortune like a magnet. The assumption that you might be able to achieve some goal if you only wished hard enough is not just a f***-up. It’s a potential personal tragedy.

Life is not some kind of rehearsal. Why, then, do so many people punish themselves in this way? The answer, in almost every case, is that they were ‘persuaded’ or hectored into becoming a banker or a lawyer when, in reality, they would have preferred to do something else entirely. Their misery is made all the worse by the realisation that had they acknowledged their lack of enthusiasm early on and stuck to their guns, their lives might well have taken a far more congenial course.

Analyze What You Want With Reason

Once you’ve figured out what you truly want, and you’re pretty sure it’s an inner compulsion and you’d enjoy the process of pursuing it, it’s time to switch into rational thinker mode from here on.

This is where we dive into a clear-eyed analysis of the desire itself.

Why bother with this analysis?

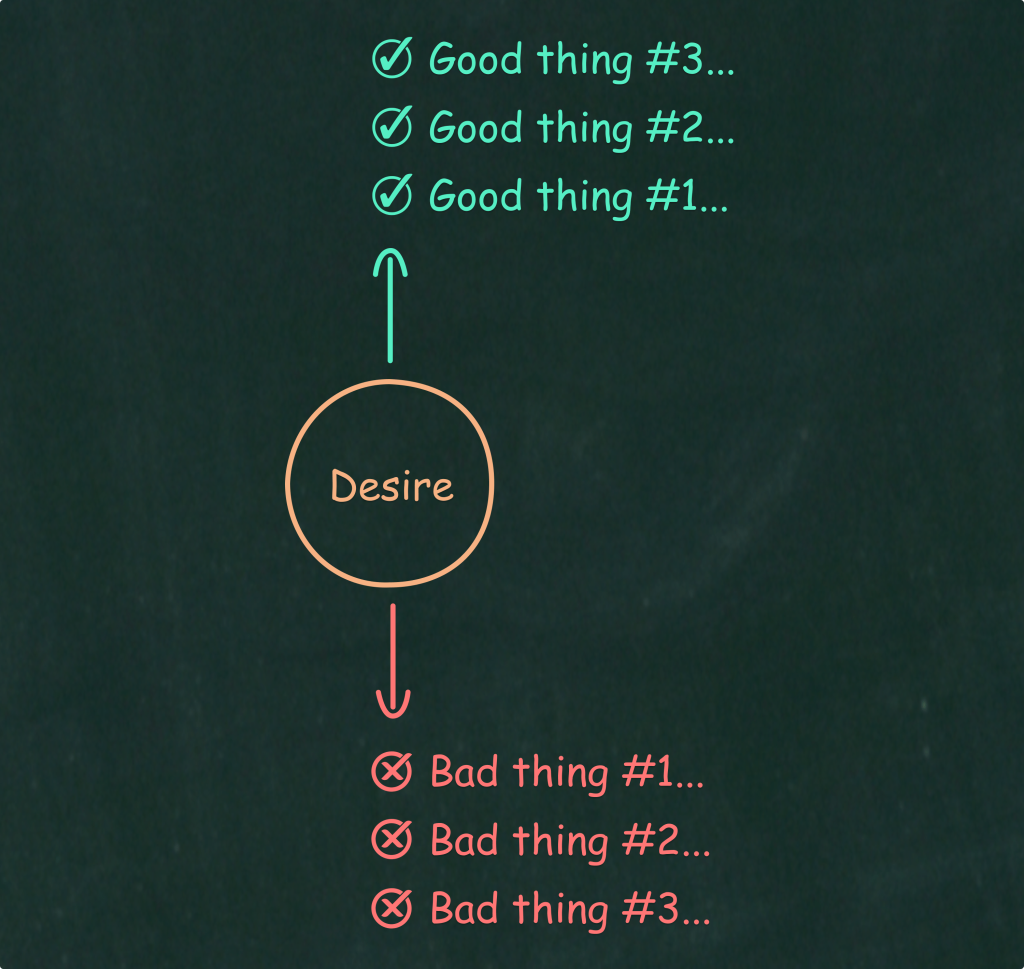

It stems from Ray Dalio’s principle:

“While you can have virtually anything you want, you can’t have everything you want.”

The key insight here is that getting what you want requires trade-offs. In fact, it’ll certainly bring along a bunch of things you don’t want, and it’s crucial to be okay with that before you start the pursuit.

To bring this point home, here’s a personal story from Jim O’Shaughnessy, shared on his podcast Infinite Loops in an episode with Derek Sivers:

It reminds me very much of what my grandfather taught me when I was just a youngster.

I had the great good fortune of living in the town he lived in, and he was quite successful.

And he would come to dinner for two nights a week.

I was 13 when he died, so I was really paying attention when I was about 11 and 12.

He taught me this thing he called Premeditate.

And what he meant by it was…

“Think of something you might want, or a goal, or whatever.”

And he goes, “Then premeditate.”

I’m like, “What do you mean by that?”

He goes, “Well, you start a list, and you say: Here’s what I want. And then you go, ‘Here’s what happens if I get what I want—all the good things.’”

But then he goes, “But then I also want you to do a list of: Here are all the bad things that might happen if I get what I want.”

And then, he had you do:

“Here’s what happens if I don’t get what I want.

Here’s all the good things that might happen because of that,

and here’s all the bad things that might happen because I don’t get what I want.”But the way he framed it to me… The first part was the one that made me kind of go,

“Whoa!”Because… What do you mean? If I get what I want; bad things can happen?

And so the unlock for me was that…

Because the minute you start doing it… You realize very quickly, “You know what? Maybe I don’t want this.” Or conversely, “I really want this.”

It just gels so beautifully with the old Daoist story about the farmer:

He lives in a little farming village, and his horse ran away.

Everyone in the village comes and says,

“Oh, we’re so sorry.

We’re just so sorry you lost your only means of farming,

and oh, this is awful; it’s the worst…”Then he said, “We’ll see.”

Then the next day, the horse returned, and with it brought a wild horse that was beautiful.

Everyone in the town rushes to congratulate him on his good fortune, and he says, “We’ll see.”

Then the next day, he is trying to break the wild horse and falls off, breaking his leg.

Oh my God! They all rush; they say how bad it is.

“We’ll see.”

Next day, the army comes through and takes every able-bodied young man into the service, into a battle they’re probably going to all die in…

And it just keeps going, going, and going.

3. Execution: The Path to Getting What You Want (Use Reason)

Once you’ve figured out what you want and you’ve analyzed it through reason, it’s time to go for it!

And at this stage, there are two critical components: (1) Focus and (2) Truth.

3.1. Focus: Burn the Boats

One of the best examples of focus I’ve come across comes from a Vanity Fair interview, where Jony Ive reflects on the life lessons he learned from Steve Jobs:

This sounds really simplistic, but it still shocks me how few people actually practice this—and it’s a struggle to practice—but is this issue of focus.

Steve was the most remarkably focused person I’ve ever met in my life.

You can achieve so much when you are truly focused.

And one of the things that Steve would say [is]: “How many things have you said no to?” And I would have these sacrificial things—because I wanted to be very honest about it, and so I say: “Oh, I said no to this, and no to that…” But he knew that I wasn’t vaguely interested in doing those things anyway. So there was no real sacrifice.

What Focus means… is saying NO to something that—with every bone in your body—you think is a phenomenal idea. And you wake up thinking about it… but you say NO to it because you’re focusing on something else.

I find it really interesting that your ability to focus comes mostly from your ability to say no to things you want to do, but that are not conducive to your ultimate goal.

Most people think of focus as avoiding silly distractions while working (like checking Instagram every 10 minutes). However, this goes much deeper — it’s about making genuine sacrifices. The kind that hurt… but are ultimately necessary.

A great analogy for this kind of focus is the story of “burning the boats”…

In 1519, Spanish Conquistador Hernan Cortez led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of Mexico under Spanish rule. Upon landing in South America, Cortez ordered his men to “burn the boats.” There was no turning back and conquering the new land was the only option for survival! Failure meant death! Do you think it motivated his soldiers to fight harder? Do you think he gained their commitment? Absolutely!

Similarly, Jeff Bezos talks about having no plan B…

[Zoya Akhtar]:

Do you usually have a plan B?[Jeff Bezos]:

I don’t have plan B’s. I actually don’t like plan B’s. I find plan B’s defocus you from plan A.

Plan B should always be: “make plan A work.”

3.2. Stay Truth-Oriented

It’s critical that in your pursuit, you stay as truth-oriented as possible, because, as Naval Ravikant says, “You can only make progress when you’re starting with the truth.”

So, if you’re serious about getting what you want, you absolutely need to use reason, and that means staying as truth-oriented as possible, even when it’s uncomfortable.

There are three key ways to do this:

3.2.1. Minimize Your Ego

The higher your ego, the more you will tend to ignore reality and retreat into a fantasy that makes your ego feel comfortable.

Therefore, it’s crucial to fight this human tendency to distort reality to make you feel good.

Remember: the goal is not to feel good, the goal is to get what you want!

And to do that, you need to work with reality, and never take it personally.

If your ego to ability ratio gets too high, then you’re going to basically break the feedback loop to reality.

– Elon Musk

[Video Source]

The best way to work with reality is to embrace the gold standards of truth: Nature and Free Markets.

Truth-seekers take feedback from nature (planes have to fly), free markets (customers have to buy), or competition (militaries have to win).

— Naval (@naval) November 14, 2024

Consensus-seekers take feedback from people (actors want fans, academics want honors, politicians want votes, journalists want status).

3.2.2. Seek Negative Feedback

Outside the realm of nature and free markets, but with the same low-ego, truth-seeking mindset, one of the best ways to kill your blind spots is to actively seek new perspectives and negative feedback from others.

The more perspectives you have access to, the better your decisions will be.

A change in perspective is worth 80 IQ points.

– Alan Kay (Renowned American Computer Scientist)

Again, you’re not trying to show off how smart you are or prove that your ideas are the best…

You’re trying to win.

You do not want to win an argument. You want to win.

– Nassim Nicholas Taleb (Author, Former Options Trader, and Risk Analyst)

3-Step Guide to Get What You Want

Throughout this essay, we’ve established when to use emotion and when to rely on reason.

And in this process of discovery, a framework for getting what you want in life has naturally emerged.

Now, I would like to compress that framework into a clear 3-step guide:

1. Figure Out What You Want (Use Emotion).

- Pay attention to what you genuinely want, rather than being guided by other people’s expectations. Other people’s expectations are their problem, not yours. Always value substance over status and prestige.

2. Analyze: Be Careful of What You Want (Use Emotion and Reason)

- Analyze yourself: Make sure that your desire is an inner compulsion and that you feel enthusiastic about pursuing it day after day.

- Analyze the desire itself: Anything worthwhile comes with trade-offs and real sacrifices. Make sure you understand — and accept — them before you dive in.

3. Execution: The Path to Getting What You Want (Use Reason)

- Understand that real focus is about making real sacrifices and a serious commitment. Be ruthless about prioritizing the actions that will eventually take you where you want to be.

- Stay as truth-oriented as possible by keeping your ego in check, embracing feedback from reality, and actively seeking out different perspectives and negative feedback.

If You Liked This Essay, Check Out These Sources

- Everything Is F*cked, by Mark Manson

- Alchemical Studies, by Carl Jung

- Rich vs. Wealthy: What’s the Difference and Which One Do You Really Want?

- Peter Thiel on choosing Substance over Status

- Zen and The Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, by Robert Pirsig

- Pain vs. Suffering: The Seed Of Your Life Story

- How To Get Rich, by Felix Dennis

- Jim O’Shaughnessy on “premeditation”

- Jony Ive on the lessons he learned from Steve Jobs

- Burn the Boats

- Jeff Bezos on having no Plan B

- The Almanack of Naval Ravikant, by Eric Jorgenson

- Elon Musk: Digital Superintelligence, Multiplanetary Life, How to Be Useful

- Winning Arguments vs. Winning in Life: Why You Are Pursuing The Wrong Thing

Mistakes vs. Regrets: How This Difference Can Transform Your Life

In June of 1996, Steve Jobs gave a speech at the Palo Alto High School graduation where he shared the following insight: Regrets are different from mistakes. Mistakes are those…