Table of Contents

The best thing I’ve read which captures the astronomical difference between formal education and hands-on training (or real-life experience) is this personal story from the trader, best-selling author, and mathematical statistician Nassim Nicholas Taleb, from his book Antifragile:

My intellectual world was shattered as if everything I had studied was not just useless but a well-organized scam—as follows. When I first became a derivatives or “volatility” professional (I specialized in nonlinearities), I focused on exchange rates, a field in which I was embedded for several years. I had to cohabit with foreign exchange traders—people who were not involved in technical instruments as I was; their job simply consisted of buying and selling currencies. Money changing is a very old profession with a long tradition and craft; recall the story of Jesus Christ and the money changers. Coming to this from a highly polished Ivy League environment, I was in for a bit of a shock.

You would think that the people who specialized in foreign exchange understood economics, geopolitics, mathematics, the future price of currencies, differentials between prices in countries. Or that they read assiduously the economics reports published in glossy papers by various institutes. You might also imagine cosmopolitan fellows who wear ascots at the opera on Saturday night, make wine sommeliers nervous, and take tango lessons on Wednesday afternoons. Or spoke intelligible English. None of that.

My first day on the job was an astounding discovery of the real world. The population in foreign exchange was at the time mostly composed of New Jersey/Brooklyn Italian fellows. Those were street, very street people who had started in the back office of banks doing wire transfers, and when the market expanded, even exploded, with the growth of commerce and the free-floating of currencies, they developed into traders and became prominent in the business. And prosperous.

My first conversation with an expert was with a fellow called B. Something-that-ends-with-a-vowel dressed in a handmade Brioni suit. I was told that he was the biggest Swiss franc trader in the world, a legend in his day—he had predicted the big dollar collapse in the 1980s and controlled huge positions. But a short conversation with him revealed that he could not place Switzerland on the map—foolish as I was, I thought he was Swiss Italian, yet he did not know there were Italian-speaking people in Switzerland. He had never been there. When I saw that he was not the exception, I started freaking out watching all these years of education evaporating in front of my eyes. That very same day I stopped reading economic reports. I felt nauseous for a while during this enterprise of “deintellectualization”—in fact I may not have recovered yet.

So, is there a difference between education and training? Yes, as Nassim’s story illustrates.

In the essay below, we’re going to flesh out this difference and also identify the five fundamental reasons that explain most of the difference, drawn from some of the most accomplished minds: Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Warren Buffett, Alan Kay, and Charlie Munger.

1. The Green-Lumber Fallacy

One of the biggest issues with formal education, and academia at large, is that it often falls for the Green-Lumber Fallacy.

You might be wondering: What is the Green-Lumber Fallacy?

The Green-Lumber Fallacy refers to a story Taleb shares, originally from Antifragile and Skin in the Game, about two green-lumber traders:

There is a story of a fellow who lost a million dollars trading green lumber. He knew everything about it: the economics, mathematics, statistics. He collected data on everything—and still lost a million dollars.

He wrote an account titled What I Learned Losing a Million Dollars, and he describes a pit trader who consistently made a fortune trading green lumber. When asked, the successful trader thought green lumber was lumber painted green—he didn’t know it referred to freshly cut wood.

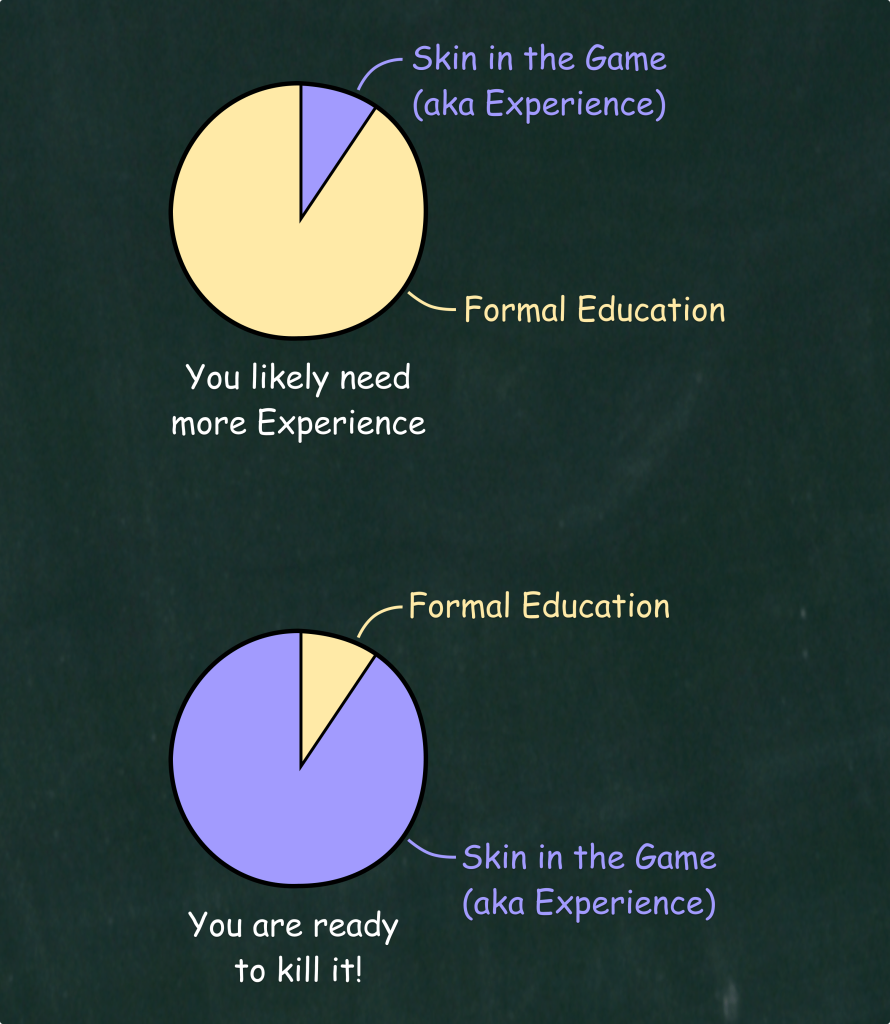

So, did that person know nothing? No—he knew a lot, but not necessarily the things outsiders would assume were important. When you have skin in the game, you learn what really matters.

Formal education makes you memorize concepts that may be completely irrelevant when executing in the real world, often at the worst possible time. It glosses over the critical 20% that drives 80% of outcomes.

“Action produces information. Just keep doing stuff.”

— Reads with Ravi (@readswithravi) October 16, 2024

— Brian Armstrong pic.twitter.com/upkfiS8YHW

The Solution

Whatever you’re learning, get as much skin in the game as possible.

If you’re studying finance, invest your own money to test your understanding of the theories you’re learning in school.

If you’re studying computer science, build and ship real apps. Experiment with tools like Lovable.

If you’re studying philosophy, live the ideas. See which ones are practical and conducive to a better life.

2. The Tendency to Rule Out “Anomalies”

Academia, especially in the social sciences, tends to ignore anomalies to maintain elegant models of reality. They make assumptions to avoid the messiness of real-world variance.

The word “anomaly” I have always found interesting—what it means is something that the academicians could not explain.

And rather than re-examine their theories they simply just discarded any evidence of that sort as “anomalous”.

I mean… Columbus was an “anomaly.”

I think when you find information that contradicts previously cherished beliefs… You’ve got a special obligation to look at it and look at it quickly.

I think Charlie [Munger] told me that one of the things [Charles] Darwin did was that whenever he found out anything that contradicted some previous belief, he knew he had to write it down almost immediately because he felt that the human mind was conditioned—so conditioned—to reject contradictory evidence that unless he got it down in black and white very quickly his mind would simply push it out of existence.

– Warren Buffet

[Video Source – 1998 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting]

Why? Follow the Incentive…

Beyond the convenience of making assumptions, academics’ survival depends on their status and peer approval, rather than reality and free markets, so it does make sense that they would behave in this way.

But when you look at people where their survival depends on reality and free markets (e.g. salespeople, entrepreneurs, investors, traders…), the focus is reversed: “anomalies” become the most important data points — because that’s what will eventually kill them (if it’s something bad) or make them thrive (if it’s something good).

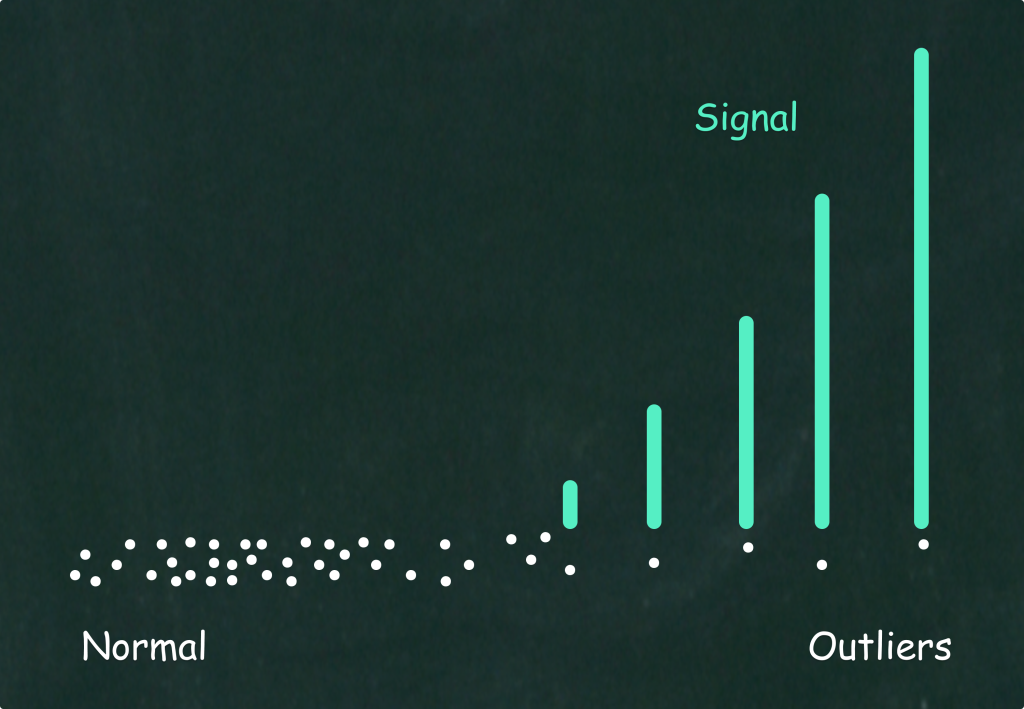

There are two possible ways to approach phenomena.

The first is to rule out the extraordinary and focus on the “normal.” The examiner leaves aside “outliers” and studies ordinary cases.

The second approach is to consider that in order to understand a phenomenon, one needs first to consider the extremes—particularly if, like the Black Swan [an unexpected consequential event], they carry an extraordinary cumulative effect.

I don’t particularly care about the usual. If you want to get an idea of a friend’s temperament, ethics, and personal elegance, you need to look at him under the tests of severe circumstances, not under the regular rosy glow of daily life. Can you assess the danger a criminal poses by examining only what he or she does on an ordinary day? Can we understand health without considering wild diseases and epidemics? Indeed the normal is often irrelevant.

Almost everything in social life is produced by rare but consequential shocks and jumps; all the while almost everything studied about social life focuses on the “normal,” particularly with “bell curve” methods of inference that tell you close to nothing. Why? Because the bell curve ignores large deviations, cannot handle them, yet makes us confident that we have tamed uncertainty. Its nickname in this book is GIF, Great Intellectual Fraud.

– Nassim Taleb

[From his book – The Black Swan]

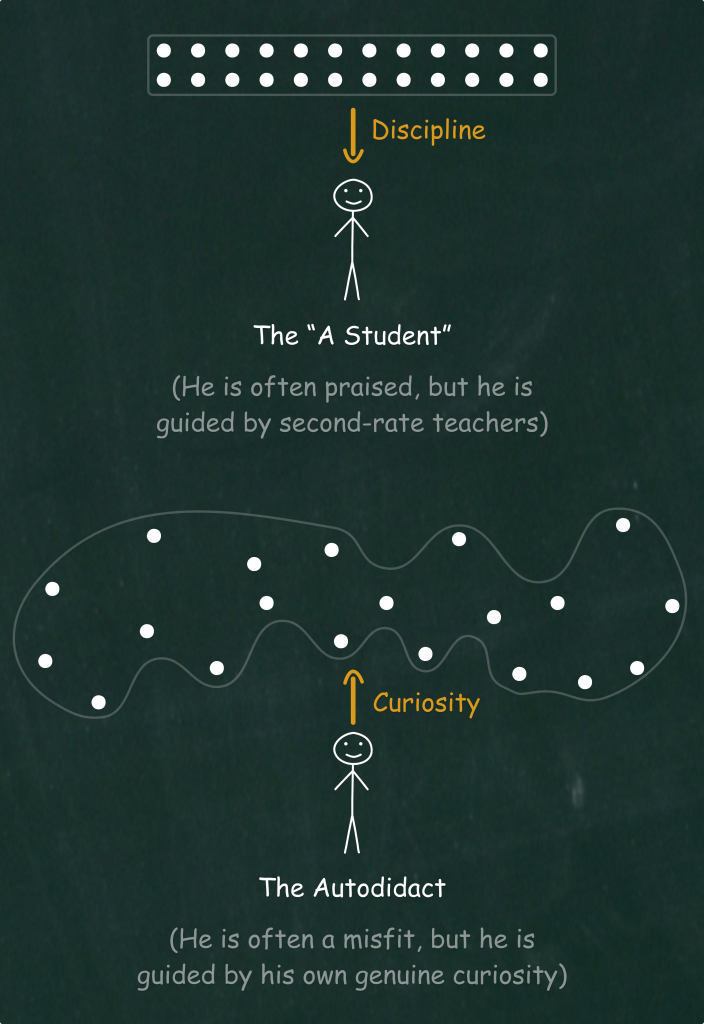

3. Formal Education, in High Doses, Kills Creativity

Nassim Taleb argues that formal education selects for people who can’t deal with uncertainty. Too much kills one’s creativity, as he explained in an interview with Bruce Orek:

[Formal] Education is not very good because—in high doses—it selects for those who don’t know how to handle uncertainty.

And this is why great scientists—like Darwin, Einstein…—are people who were not into the traditional Education System.

Simply because it kills creativity and all that stuff…

So when I was about 14 I decided to become a writer.

And I realized that if you stick to school… it narrows what you’re going to know. And to be a writer you have to read a lot of books [you need a broad knowledge].

So I started reading wholesale and it saved me [from] the bad part of Education—where you have to read a certain number of books [which] narrows your education.

And then I developed very quickly an Anti-education.

I think the only way you can learn things is if you are autodidact.

It allows you not just to have a breadth of things, but to focus on things that are really important to you—not to some second-rate person who teaches [at] High School.

[Question from the interviewer, Bruce Oreck]:

“But obviously in an engineered world, in a world that is so technically complicated… you’ve got to have some [formal] education?

[Nassim Taleb]:

It’s good to have a minimal [formal] education, but not to focus on school.

Because anything people teach you at school is useless already…

[That’s] one thing you learn as a trader: anything you’re going to read on the newspaper—say the first 15 pages of the newspaper—is of absolutely no relevance to anything… It’s already “priced in”. It’s the same way to view [formal] education.

Apprenticeship—which is more tinkering, trial and error…—it’s vastly more important than [formal] education.

As college degrees become increasingly more common in society and AI gets better and better, I think creativity and making your own path (driven by your genuine curiosity) becomes increasingly more valuable, because it’s what makes us different.

And although AI looks creative, it’s really not… It’s just extrapolating from the past onto the future — it’s not able to create new things that we didn’t know how to make.

People confuse creativity with “Oh I’m painting” or “I’m writing books.”

Creativity is solving problems. And it’s solving problems in new ways. In new ways that aren’t just simple extrapolations or interpolations of existing ways.

And that’s something that still I think humans uniquely do, that AI does not do…

AI is very effective, but it’s not solving new problems that we didn’t know how to solve.

– Naval Ravikant (Founder of AngelList)

[Video Source]

How to Boost Your Work-Life Creativity

One of the best ways to use and boost your creativity is to become an entrepreneur or to work at an early-stage (> 20 people) startup. Why?

Two reasons:

1. There’s no defined path (if there were a defined path, everybody would be rich and financially free), so it forces you to make your own path (or contribute to the path of the startup) and use your creativity.

2. You will likely have a small budget. This is great because constraints breed resourcefulness and invention! When you can’t just throw money at a problem, it makes you think deeply of new ways to solve it — and this drives invention. It’s also one of Amazon’s key principles: “Constraints breed resourcefulness, self-sufficiency, and invention. There are no extra points for growing headcount, budget size, or fixed expense.”

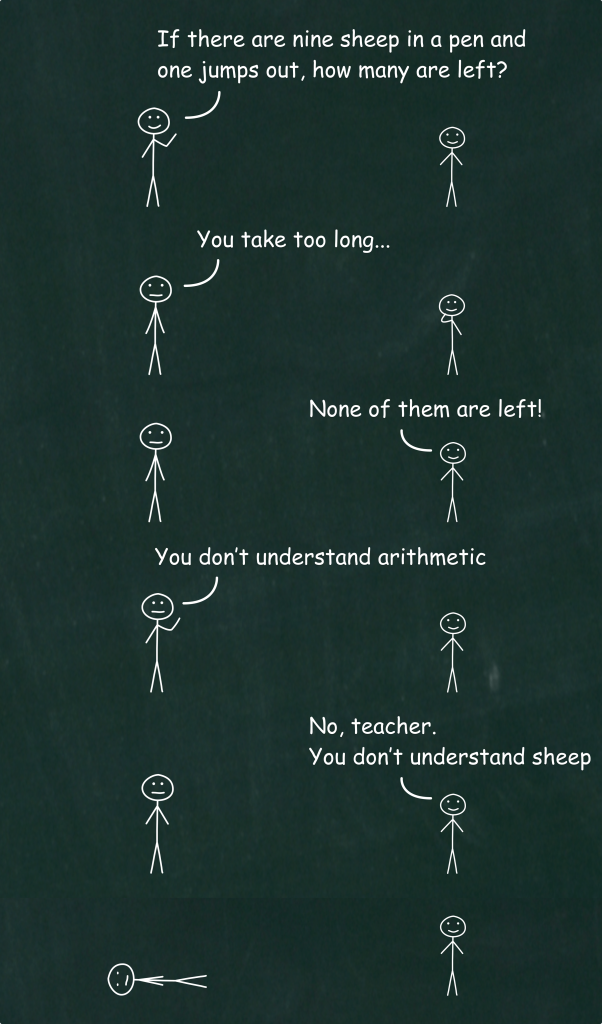

4. Formal Education Rewards Problem-Solvers, Not Problem Finders

Imagine yourself being back in school, college, or university (or if you’re currently a student, just think of a normal day of class).

And now imagine any of your teachers asking you a question — any question.

Now think about this: What was implicitly (or explicitly) expected of you at that moment? Very likely, you were expected to give an answer to the question. How could it be otherwise?

And yes… There’s an insidious and big problem built into that expectation.

The problem is that it makes you a problem-solver!

And you ask… What’s wrong with that?

The thing is that being a problem-finder, rather than a problem-solver, is way more valuable (or at least equally valuable) than being a problem-solver.

The problem-solver gets a question, and he or she immediately starts to think about solutions to that specific question, no matter how bogus or stupid the question is.

The problem-finder gets a question, and he or she first thinks about the question itself before mentally shifting to potential solutions. Because he or she understands that a big part (and direction) of the correct solution lies within a well-defined question, he or she understands that any amount of hard work means absolutely nothing if the direction isn’t the right one.

If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.

– Albert Einstein

Alan Kay, an absolute legend in the world of computer science, also said the following in a SAP Conference:

Most people are rewarded in school for solving problems…

When was the last time your child or you were rewarded for finding a problem?

“You found a new problem? We’ve got too many already!”

Whereas in fact, finding what the real problem is… Is the big deal!

And people fight you every step of the way, they’ll fight your kids in school every step of the way if they’re a “problem-finder” type.

Don’t let the teachers hurt them.

Most problems are bogus — because they come out of the current context. We’re trying to get beyond the current context.

So forget about “problem-solving.” It’s just a bad heuristic. It’s the last thing you do…

In the real world, outside of academia, it’s usually much more valuable to be a problem-finder because you will very rarely find perfectly defined questions and problems.

There is nothing so useless as doing efficiently that which should not be done at all.

– Peter Drucker

For instance, many problems might be just symptoms of something deeper and bigger. So, instead of trying to solve that specific problem, the best thing would be to figure out what is the root cause and then address it.

I believe in root causes: Finding root causes, fixing root causes… Slow is smooth and smooth is fast. Everything I have ever succeeded at in life is because of that philosophy.

– Jeff Bezos

[Video Source – Jeff Bezos Interview with AFA President Gen. Larry Spencer, Ret.]

When you address the root cause, you are not only solving the specific problem you first stumbled upon, but you are also preventing potential future problems (that would come downstream of the root problem) from ever happening.

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

– Benjamin Franklin

There’s actually a framework, called the Cynefin framework, which is very helpful for identifying the type of problem you are dealing with and solving it. It divides problems into four types:

- Clear Problems: These are the self-evident kind of problems, which anyone can see without requiring any expertise. Ex: Following a recipe.

- Complicated Problems: These types of problems require domain expertise. But there’s a clear process and solution once the expert analyzes the problem. Ex: Engineering a bridge.

- Complex Problems: These are multi-domain problems, and therefore, a domain expert can’t offer a perfect solution. The best way to solve these problems is using heuristics and experimenting (trial and error). Ex: Launching a startup.

- Chaotic Problems: These problems are novel, so there are no heuristics and you are left with only trial and error. Ex: A paradigm shift in your business or industry.

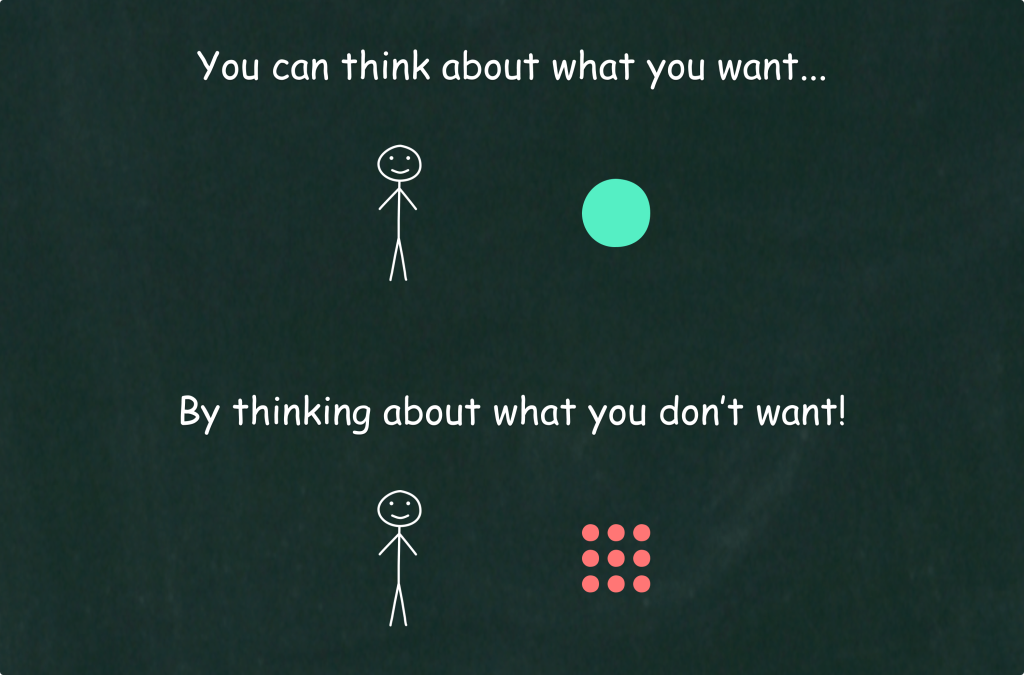

5. Formal Education Ignores the Via Negativa Approach

Via Negativa is solving problems by identifying what to avoid. Instead of asking, “What can I do to help India?” ask, “What can I do that would destroy India?” Then, avoid doing those things if you want to actually help India.

It’s a useful mental model that can give you more clarity of mind about the problem, a change in perspective, and it’s sometimes easier to solve a problem by inverting it.

A change in perspective is worth 80 IQ points.

– Alan Kay

Here’s a great example of how Charlie Munger (Ex-Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway) used the Via Negativa inversion process:

Question: You talked frequently about having the moral imperative to be rational and yet as humans, we’re constantly bearing this evolutional baggage that just gets in the way of us thinking rationally. Are there any tools or behaviors you embrace to facilitate your rational thinking?

Charlie Munger: The answer is: Of course. I hardly do anything else.

One of my favorite tricks is the inversion process. Let me give an example.

When I was a meteorologist in World War II, they told me how to draw weather maps and predict the weather. What I was actually doing was clearing pilots to take flights. I said: “Suppose I want to kill a lot of pilots. What would be the easy way to do it?” I concluded that the only way to do it was to get the planes into icing which the planes couldn’t handle or to get the pilot into a place where he’d run off fuel before he could safely land.

So I decided I was going to stay miles away from killing pilots by either icing or getting them sucked into conditions where they couldn’t land.

I think that helped me be a better meteorologist in World War II. I just reversed the problem.

If somebody hired me to fix India, I would immediately say: “What could I do if I really wanted to hurt India?” I would figure out all the things that would most easily hurt India and then I’d figure out how to avoid them. It works better to invert the problem.

If you’re a meteorologist, it really helps if you really know how to avoid something which is the only thing that’s going to kill your pilots.

You can help India the best if you really know what will hurt India the easiest and worst.

Algebra works the same way. Every great algebraist inverts all the time because the problems are solved easier. Human beings should do the same thing in the ordinary walks of life. Just constantly invert. You don’t think about what you want. You think about what you want to avoid.

When you think about what you want to avoid, you also think about what you want. You just go back and forth all the time.

Peter Kaufman, who’s here today, really likes the idea that you want to know how the world looks from the top looking down and you want to know what it looks like from the bottom looking up.

If you don’t have both points, your reality recognition is lousy. Peter is right and inversion is the same thing.

It’s just a simple trick to think about how it looks from the people above me and how it looks from the people beneath me. How can I hurt these people I’m trying to help? All these things help you think it through. And it’s just such simple tricks.

And yet, our educational system giving advanced degrees doesn’t give these simple tricks. They’re wrong. They’re just plain wrong.

Formal education emphasizes Via Positiva — what to do — not what to avoid. But in business, survival often depends on minimizing judgment errors. That’s why founders learn from competitors’ mistakes.

Learning from mistakes, other people’s mistakes, is the best way to learn.

Why learn from your own mistakes? You know, why learn from your own embarrassment?

You got to learn from other people’s embarrassment. That’s why we have case studies, and isn’t that right?

We’re trying to read from other people’s disasters, other people’s tragedies. Nothing makes us happier than that.

– Jensen Huang (Founder of Nvidia)

[Video Source – Conversation with Patrick Collison at Stripe]

Quick Guide to Excel at Each of These Five Issues

- Don’t settle for classroom knowledge. Become an actual practitioner, get your hands dirty, and generate information from the inside.

- Pay special attention to anomalous data points or events (the “outliers”) — they hold more consequential information than any data point in the normal range.

- Reduce your time spent in formal education. Maximize your time on your own projects, curiosities, and adventures.

- If a problem is Complex or Chaotic (as defined by the Cynefin Framework), which has an element of multi-dimensionality and unpredictability, always question the question! Most likely, the visible problem is just a symptom of something bigger and more profound.

- Use the Via Negativa inversion process. Ask what to avoid. Learn from failure – esp. others – and remember the pilots and the catastrophic icing.

The deeper truth is that hands-on experience builds judgment, and judgment is what really matters in an uncertain world. If you’re playing real games with real stakes, you’re learning the things that can’t be taught in any classroom.

If You Liked This Essay, Check Out These Sources

- Antifragile, by Nassim Nicholas Taleb

- Nassim Taleb on the Green Lumber Fallacy

- 1998 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting

- The Black Swan, by Nassim Nicholas Taleb

- Nassim Taleb on developing an “Anti-Education”

- Naval Ravikant on Creativity

- Amazon’s key principles

- Alan Kay on Problem-solving vs. Problem-finding

- Jeff Bezos Interview with AFA President Gen. Larry Spencer

- Charlie Munger on the Via Negativa process

- Jensen Huang on learning from other’s mistakes

Teachers vs. Mentors vs. Gurus: The Quest To Find The Best Instructor

There is confusion when comparing these words: Teachers, Mentors, and Gurus. All provide instruction, yet there are key differences in your relationship to each of them. So what are the…