Table of Contents

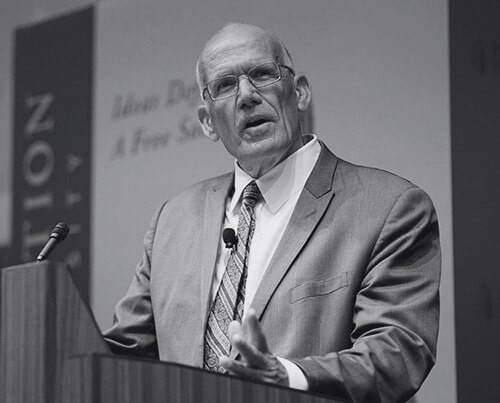

Victor Davis Hanson is a farmer, philosopher, a classicist, and a military historian. At the time of this 2004 interview, he was a professor emeritus of classics at Cal State University, Fresno and a Senior Fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institute. He is the author of over two dozen books and regularly writes for The Wall Street Journal, National Review, The Washington Times, and other media outlets.

The interview touches on familiar themes to those who know Hanson’s work: Why the classics matter, why military history matters, and what America stands for in the post-9/11 world.

Enjoy!

Harry: What led you to classics? Why did you choose that as a field, was that in graduate school?

Victor: It was very funny. I grew up at this rural high school, and I took as many advanced placement tests as I could and I didn’t really know what they were. When I graduated I realized I had two and a half years of college credit, so when I got over to UC Santa Cruz what happened was I didn’t have to take any classes. I didn’t want to. The student upheaval was just ending.

It was 1971, and there were these wonderful classes from these Ivy League professors in Greek and Latin, so I just started to take them in my freshman year and I didn’t have to take a GE. The next thing I knew, I took four years of very narrow Latin and Greek language and literature, and about halfway through that course of study they advised me if I continued I could go to graduate school.

The idea that somebody would pay me was new to me, so I did it.

Harry: Then you went to graduate school at Stanford?

Victor: Yes, at Stanford, earned a Ph.D. As I was doing this, I’m not being just practical, the message from Greek literature, Euripides, and Homer, and Sophocles, and Thucydides was tragic and practical. It wasn’t the message that I was getting from contemporary American society, so it was almost a refuge of sorts.

Journey from Graduate Studies to War Research

Harry: What did you do your dissertation on?

Victor: It was a theologically based program, so everybody was supposed to be a textual critic, and I did not want to reestablish the text for the hundredth time of a particular author. I wanted to study war, and I grew up on a farm, and I had a thesis advisor who’d just arrived and said, “Why don’t you study war during agricultural devastation of the Attic countryside, during the Peloponnesian War?”

I did and as a sort of penance, I had to have the first chapter of first chapter on philological study of all the Greek words for ravaging. UC asked me to come out with it, and I came out in 1998 with a new edition.

Harry: That book is The Western Way of War?

Victor: Actually it’s called Warfare and Agriculture in Classical-

Harry: I see. Okay.

Victor: Then I edited a book called Hoplites, and then I wrote The Western Way of War.

Harry: Later?

Victor: Later, yes.

Influence of Family Military History

Harry: Okay. What is evolving here as you make this journey is an interest in classics, a real knowledge of farming and so on, but also an interest in war. I get the sense that recollections of war from family members who had been lost as soldiers or for example, your father who had served in World War II. Tell us how that-?

Victor: While I was growing up in this rural family and at Thanksgiving or dinner, every day one table was my grandfather’s Frank who was gassed in the Argonne in 1918, and he had trouble breathing. Then my father was next to him and he had flown 39 missions in a B-29 over Tokyo, and then they would talk about Victor who I was named after who was killed on Okinawa. Then there was Vernon who had been in the Aleutian Campaign.

Everybody there had certain attitudes about Europe, war, hard work. That was sort of the frame of reference, but I was more bookish I guess. I would study these things they would tell me, I’d come back at dinner and say, “Well, dad did you know on March 11 there was actually 742 B-29s?” It was a mixture of first-hand recollection with abstract study.

Harry: You were interested in it?

Victor: I was. I was fascinated about human nature and conflict, and especially war as an arbiter, the ultimate disagreement and that sometimes it had a utility that things were solved by war. My parents made us go to school in a very rough neighborhood, it was about 75% of the people had just arrived from Mexico and the public school system. My father kept ingraining it in us that when you were at the local schools it didn’t matter who you were.

It didn’t matter how bright you are, it didn’t matter if you’ve got straight A’s, it didn’t matter anything. When you got out on the school ground there would be people who would- All the things that made you a good person, good grades, following the rules, being polite, they would hate you for it because they would see that as weakness or arrogance and that nobody would be there to help you.

That, you had to not only protect yourself but try to help people were not able to protect themselves. I think I got a hundred lectures about bullies, so I had a lot of fights when I was very young and I still live in the same neighborhood. My children had to go to the same schools and they’re much worse.

Harry: You’re suggesting that even as a young person the ideas that you had about the world were tested by reality?

Victor: I think they were because I saw a lot of things on the farm. Farming is the most dangerous of all occupations, and I saw people maimed. It happens that my brother cut his finger off the other year, and there was constant injury. Then going to school were fights. Trying to keep this farm, it was not suggested that this was an economic issue, people like my grandfather would say, “We’ll see if you can keep it the way I did. People will come and try to take it away from me.”

They had a Hobbesian view that nothing was static. There were forces out there that always wanted to take things, and people who tried to stop them and this was a tension in the world that would never end.

Harry: Was this background conducive, supportive to your focusing on Greek studies? As you went through this literature, as you mastered this material, I guess then it resonated with this experience because the Greeks really did focus on agriculture and war?

Developing a New Perspective on Warfare and Agriculture

Victor: Yes. I noticed a couple of things that everything in classics that had been written about war was written mostly in German in the 19th century and had very wonderful things but was discredited because of Germany’s later performance in World War II and World War I even. Nobody had written anything about agriculture because they didn’t have any practical.

As I started to investigate it, I realized that Greece is at about in the same latitude that I grew up at. It was a Mediterranean climate. I knew a lot about vines, and wheat, and olive trees. I was interested in war and the field was wide open. I remember going back to one of the advisors at Stanford and saying, “There’s not one title in the card catalog with word “agriculture” in association with ancient Greece since 1922.”

I was trying to override their skepticism about studying that.

Harry: When you left Stanford, you went back to farming though. You didn’t practice your classics right away?

Challenges in Establishing a Classics Program

Victor: No. I finished pretty quickly, and I lived in Greece for two years doing the archaeological part of the research, and I came back in 1980. I had a brother who had dropped out of medical school and my grandparents had passed away. My parents were living in Fresno, and the question was if somebody doesn’t run this ranch we’re going to have to sell it. The three of us ran it and we did a lot.

It had fallen in decay during my grandfather’s later years, so we put a new irrigation system. We built sheds, we redid it, and by 1985, unfortunately, that was right during the agricultural collapse, so I went and got a job. I was lucky enough there was a university within commuting distance. The bad news was they had never had a classics program. It was very hard to convince them they should be teaching Latin and Greek at Fresno State.

Harry: You really established a program there, right?

Victor: I did, there was nothing there. I started off as a part-time Latin teacher. The next year I offered Latin and Greek and I taught five classes a semester for probably eight years, and then I was lucky I hired more colleagues, and now we have four people. It’s a very good program.

Critique of Modern Classics Studies

Harry: Over time you became disillusioned with the study of classics generally in the United States. In fact, you even wrote a book with a co-author called Who Killed Homer, I believe, which I can show.

Victor: John Heath was a student I had met at Stanford, and he had started the same thing that I had done only in Florida. We had talked over the years about why it was that all the values that reflected Greek values, egalitarianism, education, practicality, pragmatism we’re not being honored by the profession. In other words, it was becoming highly theoretical.

The key was not to teach, it was to publish for narrower and narrower audiences. It was not to use the clarity of the expression that Greeks had embraced, and it was careerist. We wrote sort of a diatribe or a critique about the profession and why such a wonderful thing as classics was down to 600 majors a year and I think 4000 classicists.

Harry: Throughout the country?

Victor: Yes. In that tiny world of classics it had an earth-shattering effect [laughs] if you can say that because we quoted research, we quoted what people wrote. People became hysterically angry because the world really hadn’t paid any attention to classics but now it was being discussed in larger venues and the only message that was getting out was our message and they didn’t think that was fair at all.

The Relevance of Greek Studies Today

Harry: Why do the Greeks still matter because you were focusing on the Greeks at a time when one could say that nationally we were in a sense losing our commitment and understanding of what Western civilization meant?

Victor: A couple of reasons. Historically, there is no West before the Greeks. Even in Greece before the 7th-century you had the Dark Ages and the Mycenaeans who are not Western in the sense as we know it. This idea of what is consensual government? What’s capitalism? What’s freedom? What’s individualism? What’s secularism? All of these ideas were not only apparent in Greece but they were discussed, the contradictions of them.

Is it good to have democracy? Is it good to dump culture down to the lowest common denominator? Is it good to have religion as a state religion or as a coercive mechanism to instill good behavior? All of these things that we wrestle with today were discussed by people who in some ways were not confused by technology, they were empirical. They just wrote down the world that they saw.

I thought that the message had been lost. They had this, as I said, the tragic view of the world. That we all die, we all grow old. It wasn’t “old age is the golden years” or it wasn’t “Isn’t this wonderful that if you have a divorce or you have a death in the family we can learn from this”. No. It was bad and so there was an honesty in expression and appreciation about tenuous life was and how appreciative you should be to have shelter and food.

Connecting Military History with Personal Experience

Harry: Now, over these years you were also focusing on being a military historian. The Greeks had a lot to tell us about the war that we were losing sight of in this Post-Vietnam era.

Victor: Yes. I think what happened was that military history as a discipline was discredited after Vietnam. There was a few people, John Keegan in England surely was one that wanted to look at it as a social-cultural phenomenon and I did. I wrote a series of books that tried to suggest that this is the way that Westerners fight. It’s predicated on cultural and political assumptions.

This is how it relates to society and it’s immoral in the sense that war itself is not bad, particular wars are good or bad. I tried to establish criteria for them so I wrote a series of books in comparative military history. It was a lot of work because I had to go to the Civil War, the Ottomans and I went beyond classics.

Harry: One of your major books was a book called The Western Way of war. Tell us about what you found there. I believe I read somewhere that one of the things that struck you as you were getting into these studies were there were notions about the destruction of Greek farmland in warfare that didn’t make sense to you because you were a farmer.

Victor: The standard opinion was that armies went in, a historian like Thucydides or Polybius would say they ravaged the land and they were trying to starve the enemy out. There were problems when I re-examined that I would see things like they came every year. Well, obviously, they cut down all the olive trees, there’d be no need for that. Growing up on a farm I notice it was very hard to cut down an olive tree. It’s very hard actually to burn grain except for a brief window.

I realized that there were physical problems with doing it and more importantly I started to see these psychological ramifications that it was a catalyst to insult the pride, to instill anger. From that germ, I began to reread Greek literature for the first time and I ask wider questions, why do people go to war? Is it always because of materialism?

This is very unpopular because at this time in classics, Moses Finley and other people were talking in very Marxist terms about material reasons and the idea that it could be in the Greeks’ way psychological or spiritual and about honor and fear and envy and jealousy was considered crazy.

Harry: In the Western Way of War you actually helped us understand what Greek warfare was like in this period from 700 BC to 340.

Victor: Probably 700 to 350 or 340 BC.

Harry: There was a real integration of the way of life of the soldier and the kind of war they fought and the way it was fought. Tell us a little about that.

Victor: It was in a Mediterranean climate so there was a campaigning season that was predicated on the agricultural year. You were a farmer and a militiaman so you had your own responsibilities back home on the farm and so you couldn’t be away from your farm very long. Usually, it was a consensual government, they had to have a majority vote. Usually, these two sides would meet by I guess convention.

They would meet a flat plain, they’d put on this absurd heavy armor because they had like purposes. They crashed together and then there’d be an artificial understanding that the one who won would establish a trophy and then the question would be resolved, usually it was pretty worthless borderland. As this got going, people began to realize that it was both economical but absurd because one army might have reserves or one army might have a big Navy or Athens might have light-armed troops or might not.

It was artificial especially when you met the Persians and you saw that this was a whole different challenge. I was very interested in how this system unwound and the social ramifications of letting people fight who didn’t own land, who weren’t citizens, who were former slaves. The question of utility versus efficacy or honor. It was very interesting.

Harry: Was there a corruption of the political system that had worked so well in this earlier period?

Victor: There was. There was also honesty to it. It starts actually with Athens that democracy that was not a landed oligarchy. I guess I could sum it up by saying, who are you farmers to decide that the whole city-state should rest or fall within one-hour ceremonial collision when we have other assets like walls that we can hide behind the walls or we don’t have to come up and fight or we can fight at night or we can poison the water or we can fight at sea or we can fight with arrows?

We have all this literature from Homer onward criticizing the slave, criticizing the bowmen, criticizing the spear thrower, javelin throw. What was interesting is the more warfare became democratic and was not predicated on the social class, the more destructive it became and the more amoral it became.

Harry: In this earlier period, there was a movement toward a decisive finite war which was very nasty but which put an end to the matter.

Victor: Yes. I think that was important because that idea, even though it was no longer an infantry battle survived in Greek thinking, that if you had a sea battle the point was to destroy the enemy’s assets. This is important because there’s a lot of other traditions, the nomadic tradition or the Chinese tradition or the tradition in Latin America of ceremonial wars of hostage-taking, of anthropological explanations for it, cattle-raiding or fighting a world where you are the indirect approach.

The idea that when war is declared you find the enemy’s military forces, you find the quickest way to get there and destroy them and get home, is very familiar to us in America today.

Harry: As a military historian I want you to help us understand what a military historian does. I mean sorts of what problems interests you?

Victor: Well there’s the discipline in military history that has clear-cut rubrics or subdivisions. There’s logistics, there’s the grand strategy, there’s tactics, there’s what we call operational history about how divisions fight battalions or how horsemen fight. Then there’s economic social military history, gender, race, class as it pertains to war. All of these are traditional military history.

As military history came into its own, it seemed to me that operational history, tactical history, strategy and especially the experience of what it was like to fight was pushed away. We saw military history to be acceptable it had to be social history. What I was trying to do was to bring back the question of tactics, strategy, and the face of battle. To use John Keegan’s term “back into the mainstream” and do it in a different way so that I wasn’t seen as just a Prussian military officer but seen as something that the strategy or tactics or the experience of battle rippled out or affected communities or it was not just an esoteric science.

Okinawa and Its Historical Impact

Harry: One of your recent books, which I think I have here is Ripples of Battle. Let’s talk a little about that as a case study. You focused on three battles important in history. You really begin this exercise with a quote from Churchill, “Great battles change the entire course of events, create new standards of values, new moods in armies and a nation.” In this book, one of the battles you focus on is Okinawa.

The story you’re telling there has really ripple effects within World War II, beyond World War II, but also among families, your own families.

Victor: It does. I was trying to show that there is something abnormal about a battle. You put a bunch of mostly young men throughout history in a confined space, in a confined time and the stakes are one’s life, they see ghastly things and those impressions then affect them for their long span of life in a way that maybe even getting married or having children or farming or buying your first car do not and that a lot of literature and drama and philosophy come out of that.

I wanted to make that argument first. It’s not predicated just on numbers of dead. Plague and earthquake kill people much more than wars do sometimes but they don’t involve these issues like culpability or preventability or human agency. I wanted to look at three of them, a modern one in Okinawa, one at Shiloh and then a Greek battle at Delian to show that the same issues were constant throughout time and space.

In the case of Okinawa, I had grown up hearing about how this battle had killed this young Swedish American farmer, a farm kid at 23 just after he got his bachelor’s degree in 1945 and nobody wanted to talk about it and they were all dead now. I wanted as a personal odyssey, reconstruct and explain how that death had affected all these people I know but then lead that as an entry into the battle itself.

Harry: This was your namesake, the person you’re named after him, was a cousin.

Victor: He was my father’s first cousin. His mother died in childbirth and his father left ao he grew up with my father. They were the same age, same height. They looked almost identical. They had joined the Marine Corps together. They had gotten in a fight with an officer and as punishment, my father took the rap and they put him in these new experimental B-29s which turned out to save his life.

To stay in the 6th Marine Division was, if you look at the casualty ratios in Okinawa of the 29th Marines it was a death sentence. Nobody knew that at the time. I was interested in how he died. I knew that would be almost impossible because 83% of his battalion that went up Sugar Loaf Hill was dead by the time he died. This being 58 years, I didn’t think there’d be anybody alive but I found actually seven people who were there when he died.

Harry: The battle of Okinawa occurs toward the end of the Pacific War. It’s a major island right near Japan. Over 90 days, the Japanese lost probably 100,000. We lost 12,000 soldiers, maybe another 100,000 civilians were killed. It was a really horrendous battle to take a well-fortified island and the costs and casualties were really quite heavy but it was important for moving on to Japan.

Victor: I think it was. It was the idea that as a funny battle that it was started on April 1st and it was ended July 2nd and then in 60 days later the war was over. The American people woke up and they really didn’t know what was going on for two reasons. One, Franklin Delano Roosevelt died right at the beginning of the battle and then Europe was liberated and the war was over in early May.

While their attention was focused on Europe, they didn’t realize there would be 50,000 casualties, 350 ships hit, 5,000 sailors killed, 7,000 Marines and Air Force. This worst fighting of the entire war. In fact, they were killed days where Okinawa was the worst day for the Americans in World War II. That was striking. What was even more striking is what the purpose of it was.

It was to get a gigantic island 350 miles from the Japanese mainland. While we today worry about the atomic bomb, we have no idea what Curtis LeMay was thinking of bringing the 3,000 B-29s and rather than having to fly 1,500 miles from the Marianas, they could fly three sorties a day. Although they’d almost burned down the cities of Japan already, they could do this day in.

Why not bring all the B-17s in and even the B-24s and even the Lancasters? In his mad mind, he had this idea of 15,000 bombers, 350 miles from Japan. It would have been a holocaust. I tried to just discuss that. Also, we worry about the bomb and the moral implications of that but-

Harry: The dropping of this atomic bomb.

Victor: Yes, in August but we have completely forgotten that that generation asked different questions and that was, “We killed over 100,000 Japanese soldiers. They and us together killed 100,000 Okinawans and then we had 50,000 American casualties. When this was all going on, we had a bomb that was almost ready for production. It was tested in July. Why didn’t we just hold off and use this bomb and then we wouldn’t have had all these people dead?”

That generation’s call was not, “Don’t use the bomb but use it earlier.” It had an enormous effect on what we envisioned for Japan because there were suicide boats. There were suicide submarines. There were suicide battleships, the Omoto and there were suicide, of course, planes, there were suicide corpses. The Americans had never ever experienced anything like that.

It made Iwo Jima look like a picnic if I could say that. The idea that there were still 12,000 kamikaze planes on the Japanese mainland and there was a militia of five million people. It would be staggering to see Okinawa replicated at a magnitude of say 10 or 20.

Harry: This really impacted on the decision about the atomic-

Victor: Yes. You can’t understand the dropping of the atomic bomb unless you read about what went on in Okinawa and what the Japanese militarists said. They had written instructions that one man can take 10 out or take a tank and they’d had a year to fortify the island and it was designed by the Japanese to show the Americans that, “We can make life so horrible for you and you can’t take casualties like we can.

You better think about a negotiated surrender of ours rather than unconditional surrender. The militaries could stay in power with the threat that if you try to invade the mainland, it’ll be another Okinawa” They were successful that way.

Challenges of Modern Terrorism and Military Strategy

Harry: In a way, this is a first run for what we’re now encountering in terms of suicide bombers in the Middle East?

Victor: Yes, it is for two reasons. One, the tactic of putting a man in a plane and trying to blow up things or a person on the ground trying to do it and more importantly the whole idea that a Western affluent bourgeoisie society cannot suffer the same degree of casualties as a militaristic society. Make war so terrible that even though we lose 10 times more than you do, your loss is felt more grievously.

The only thing I can’t quite understand about the Islamic fundamentalists who are terrorists is that they didn’t really learn the lessons, as we saw the other day in Fallujah, that the West always has a response to this. Now, it may be horrific but it will draw on its capital, its technology, its discipline to come up with a remedy. The only thing that stops the full implementation of that remedy is usually a sense of self or moral restraint.

Something about suicide bombing is a liberating experience for a Westerner. When they encounter suicide bombing, it’s almost as, “If these people are going to do this to us, then there’s no other way to win the war but to unleash the dogs of the American militarism.” That’s what we did and we’ll probably do it again if it happens again.

Harry: You write that, “The pool of those who wish to kill themselves in service to a lost cause is finite despite professed fanaticism.”

Victor: Yes, it’s so funny that we had this idea that was every Japanese person wanted to be a kamikaze. In fact, there was about 7,000 people that did and most Japanese hated the tactic. After the war, the people who had inaugurated the tactic were despised. They had to finally get people out of the universities who were English majors of all things. They had to intoxicate people. Today it’s kind of nostalgic and even Japanese people look back in glory but not at the time.

There was a finite number in the final kamikazes. The biggest problem was in the latter days of the campaign they were not flying their missions and the fighters who went along with them were instructed to shoot them down if they don’t go. I think you’re seeing the same thing after three years in the West Bank that if you start looking at the profile of suicide bombers we’re seeing a lot of people now who are under psychiatric help, who are in a messy divorce that’s impugning their honor, they’re caught with adultery.

There is a finite number whether it’s in Japan or the present-day West Bank who are willing to do that. If the West or whoever is against suicide bombing- because it doesn’t seem to be a Western phenomenon, if they’re willing to recognize that and to put up deterrence and to wait it out and then to use its own advantages in a counter attack it’s not successful.

that’s impugning their honor, they’re caught with adultery.

Harry: Before we talk about 9/11 and its impact on the United States I want to ask you, in doing this research on Okinawa for this book you actually found someone who sent you a memento.

Victor: I was talking to a lot of these people about how Victor Hanson was killed and one of the funny things was one of them said, “Didn’t you get my letter?”

[laughter]

Victor His letter was sent in 1945, so I went out and found an old letter at my grandfather’s. He sent me a copy of it. Now he’s 87 and he was 30. Another one said, “Why didn’t anybody call me when I had Victor’s ring?” I said, “What ring?” He says, “He was so proud of this Legionnaire ring that he wore in training at Guadalcanal.” I said, “No.” He said, “he had a premonition he might die and he wanted us to take it back.”

I said, “What would he do, he didn’t know classics?” He said, “No, but he had a Roman Legionnaire.” I was a classicist, so I was interested in him as well. He muffled and he said, “Let me go off away from the phone I’ll call you back.” He called me back a little bit later and said, “I have it here. I remember now that I called your grandfather and he didn’t speak English well and he didn’t want to come to the phone. I have it and I’ll mail it to you.”

I didn’t know whether it was age or senility but sure enough this thing came and then I had pictures of him and you could see it on his finger. They had cut it off, when he brought down he was bloated the next day and they cut it off his finger. It came in the mail and I put it on this so here it is. That’s his ring.

Harry: This is almost Greek or mystical in it.

Victor: For me it is and I wear it around my neck 24 hours a day.

Harry: That history would bring you back to the personal.

Victor: It is. I remember the name, of course, I never met him but when I went to school my father went out to the barn and said, “Here’s his briefcase. Here’s his baseball bat. Here’s his papers now. I don’t want to talk to you about. I don’t want to know anything about it.” He couldn’t talk about it. He just said, “You’re supposed to be a better person.”

Growing up in this small rural community every time I went to the doctor there’d be a very attractive nurse in the 50s or so he’d dated and said, “I was in love with Victor Hanson.” Or I’d go meet some guy, “This guy was six-two, you’re only six-one. He spoke Swedish, you don’t speak a word.” My whole life I was haunted by him and a wonderful person.

Reflections on 9/11 and Its Historical Precedents

Harry: Let’s talk a little now about 9/11. Did the 9/11 attack in some funny way bring us back to the Greeks and what they had to tell us?

Victor: I think so. I think most people had thought that we were at the end of history that globalization or westernization had created a uniformly affluent interconnected world and that in the United States during the 90s we had a booming economy we were like a dog that was asleep. Every time we hear these strange places like Khobar Towers or Tanzania or First World Trade or USS Cole it was swatting a fly.

The idea was almost,” They’re military people or they’re diplomats. They can harvest a few. That’s not serious.” Suddenly, the worst attack on America as a precursor to war in our history more than Lexington, Concord, Sumner, Havana Bay, Pearl Harbor. It really shook us up. The question is, what are you going to do about it? We talked about a coalition government in Afghanistan, we talked about Pakistan, UN peacekeepers.

Suddenly, out of the past, we started to hear voices that would say, “No, these people want to kill you and they’re going to keep killing you until you stop it.” You either stop them or give up.” There were a majority, not a great majority, but there were a majority of people in the United States I think understood that in a way that maybe Europe didn’t.

Harry: You wrote, “Awful men cannot be cajoled, bought off, counseled, reasoned with, or reported to the authorities, but rather must be hit and knocked hard to cease their evildoing if the blameless and vulnerable are to survive.”

Victor: I think the point that we should keep in mind with all this is that there were thousands of Afghans that were killed, hung, tortured. Half of our species, all the women in Afghanistan were relegated to medieval status. Same thing in Iraq. Every time some Westerner has embraced utopianism and the idealism of reason as the ultimate arbiter of disagreement, somebody else less affluent, less privileged pays for it with his life.

Actually, the use of force if it’s done in a legitimate way and it’s done carefully and it’s thought out, can save far more lives than would be lost. I was appalled when I heard people in the United States make these predictions of millions of people would die in Afghanistan. The United States is culpable when we had watched this horrific regime destroy an entire country and had done nothing about it.

Finally, when we woke up belatedly and we’re doing something about it people didn’t understand.

Harry: One of the ideas that had developed after the Vietnam War was the notion we really as a democracy couldn’t allow one American soldier to be killed. If we lost one soldier that the politicians had to run for cover because the people would turn them out. I would like for you to talk a little about the synergy between democracy and war because the fact of the matter is it often can cut the other way.

In other words, that when you have a functioning democracy that confronts a situation like 9/11, that not only can it marshal the technology and the resources but it can really rally forces for a war against the adversary.

Victor: There’s a pro and con about democracy at war and it’s discussed at length in Thucydides’ history, especially the Sicilian campaign. That’s one place. Polybius talks about an association with the Roman in times of peace because of the success of the rule of law and usually, there’s a better economy in a democracy than non-demo. Life is pretty good and because people run their own government they have a tendency to (a) vote themselves entitlements, and (b) try to avoid risk than any one person.

That can be fatal as we saw in France in 1940 or we saw in Athens in 340 BC when they were threatened by Philip. That being said if a democracy wakes up and is attacked and mobilizes all of its resources and has a majority vote there’s no ultimate appeal, no second-guessing. You don’t say, “Franco made us do this.” “It wasn’t me, it was Hitler.” “Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait.”

No, the democracy, the people themselves have a stake in it and they’re constantly auditing the conduct of the war and the ultimate check on that is their own sense of fairness. If you attack a democracy and you kill a lot of people in a democracy human nature being what it is, they’re going to vote to take reprisals. Democracies when they’re aroused make war like no other type of government.

Harry: I get the sense that from your writings after 9/11 that the other thing that resulted from the battle of that day when we were attacked was that we had to rethink or be reminded of what it is we stand for.

Victor: I think what has happened to us since Vietnam is that because of our success whether it’s civil rights or the environment or equality of the sexes, that we have created even increased appetites for greater success. If we once wanted to ensure an equality of opportunity with freedom and liberty being the objects for everybody, now what we wanted is almost an equality of results; egalitarianism and equality were more important. That is hard to do.

Human nature, again, to use that hackneyed phrase telling us that we’re not all born into this world equally and to by coercion make us equal. Once you have that mentality and you have a vibrant economy and you have a leisured society, then you can lose touch with reality very quickly. We had this hyper-criticism that if we’re not utopian we’re not perfect then we’re utter failures.

Immediately after 9/11, there were people whose voices we heard, “Wasn’t Afghanistan part of the British Empire.” It was either cultural pessimism. “The peaks are too high.” “The Northern Alliance is unreliable.” “We didn’t have our hands clean.” “The British never won.” “The Russians never won.” It was either pessimism in the thought or it was hyper-criticism of, “Didn’t we withdraw after we got the Soviets out and didn’t somebody give aid to Osama bin Laden?”

Without any knowledge that that’s the stuff of history, that nobody in 1944 would say, “Wait a minute. We gave 375,000 GMC trucks to Stalin. We gave him probably 30,000 P-39 Air Cobras. This was a man who butchered 30 million of his own people and we used him cynically to fight the Nazis.” No, they didn’t think like that.

They said, “For now, at this time in this place, Hitler is worse. When Hitler’s gone, we’ll turn our attention to Stalin, but we’re not going to judge ourselves tainted or fouled because we’re helping people who are mass murderers to kill a greater mass murderer.” It’s important that Americans get out of their cocoon and wake up and realize that they don’t have the ability to demand or achieve perfection, not in this world.

Harry: You really believe that we do confront a clash of civilizations?

Victor: I do. What I am absolutely astounded by is the clear-cut clash of civilization. We’re talking about a minority group of perhaps one to three million people of the larger Middle East who are Islamic fundamentalists and all the Western tradition and liberalism they hate. Take your pick. Homosexuals, kill them. Women, no rights. Polygamy. Clitorectomy. Consensual government, no. Tolerance for Jews and Christians, no. Hindus, no. Buddhists no. Patriarch, absolutely.

How are they successful? Because whether it was colonialism or anti-communism or realpolitik or just endemic tribalism, the Middle East is not with it. When it can’t feed its people, it can’t house them, it can’t educate them and it won’t make these reforms, they turn their animus, their frustration, and their state-controlled media to America and the Jews. The conduit from the frustration to the media is often these Islamists.

The only way to rectify that is to defeat them and to humiliate them and to offer the people who follow them an alternative and get away from supporting the Saudi royal family or the Kuwaiti royal family and try to do something that would lead to integration within a larger world community as we have done in Latin America and Asia.

Harry: Do you think that the United States with the erosion of values that had occurred in the last couple of decades, is it able to muster the wherewithal to engage in this conflict and succeed? I know we have the military resources and we have a very talented and trained military that can win the military victory. The question is can we stay for the long war in the context of what we’ve become at home because of affluence and all our other resources.

Victor: I think we can but to be frank with you, if it’s a question of New York and Washington DC and Los Angeles and San Francisco and Seattle winning this war I don’t think we can. There are people who get up in the morning and they go wait tables or they drive a tractor or they go pick up a criminal and they live in a real world and they understand that there’s a thin line between civilization and barbarism.

They’ve seen Saddam Hussein and they’ve seen Osama bin Laden in their own world and they have no compunction about eliminating him. They’re just driving up today to talk to you. A man was just killed, 41 years old, Army Major, left his six-year-old son. He was a surgeon, he’d just e-mailed his parents that he was this time off from battle surgery. He was doing free appendectomy for Iraqis.

They blew him up and killed him, murdered him. They knew that he was there not to take their oil. They knew he was there to try to institute a liberal regime. I listened to his parents, did they want to sue the government? They were from rural Wisconsin. No. Did they blame the military? No. What did they say? They said, “The world lost a wonderful person. The United States lost a great patriot. He had no regrets, he knew what he was doing. It’s a tragedy.”

That is what America was all about, I think, but you wouldn’t hear that in many places. We’re in a war of the hearts and minds for America. We’ll see how many Americans are confident and proud of what the United States is and how many are ashamed of it and think it’s the source of evil in the world today. The latter group is larger and will lose like every other society that eroded and drifted away.

Harry: What is the challenge of leadership, that is, American leadership in the context of this dilemma?

Victor: You can see it with the president. The president is very, very good. It reminds me of Archilochus’ metaphor of the fox and the hedgehog. Bill Clinton could think of a thousand things and express himself wonderfully and not come to a decision. Bush is not glib, he’s not sophisticated. He sees right and wrong and that’s what you need in war. The only problem that I have is that he needs to remind America this is not about weapons of mass destruction.

This is not about the world’s oil supply. This is not just about 9/11. This is a war with a type of enemy who if its agenda was realized would end all the things that we think are dear. He needs to remind the American people that the Japanese like to import oil so that the world can have Honda’s or Toyota Prius is trying to deal with the environment. The Europeans like to trade and sell farm equipment to the Middle East.

There’s a sophisticated world. People like to go study at Harvard from Jordan. That whole system is based on certain trust, certain protections that these people, these terrorists, and Islamists would destroy, as we see in Spain, as we see in Turkey, as we see in Morocco. This is the face of barbarism and they’ll either win or lose.

Harry: Obviously, part of the problem here is to win a military victory but beyond that how do you win the battle of ideas?

Victor: I think we should give ourselves some credit. We realize it can’t be won with ideas and it can’t be won with force. It has to be won with both. Militarily, we’re going to defeat autocratic fistic governments either now, in the past, that sponsored, aided, abetted terrorists. At the same time, we’re offering them the carrot and saying this is the new United States.

Look at Panama, look at Milosevic, look at Taliban. We’re not just saying, “Pump oil. Keep out the Russians, the Shah of Iran, Saudi royal family.” We’re doing something differently and we’re trying to spend blood and treasure to give you an alternative to Bin Laden. If you don’t want it you don’t have to but we’re going to get rid of Bin Laden and we’re going to get rid of what he stands for and that’s all we can do.

We did it with the German people, we did it with Japanese, we did it with less success in Korea. We did it with no success in Vietnam but we’re going to try to do it and we’ll give them the alternative.

Preparing for the Future with Classical Wisdom

Harry: Looking down the road, how would you advise students to prepare for the future, for this world that you’re describing in which some of what the Greeks taught us really helps us understand that world and virtues like character and courage, and so on, matter? How should they prepare for that world?

Victor: I think they should realize that the skills that make one successful in 500 BC may be the same today. It’s not just adapting to a new technology or a new lifestyle, it’s realizing that a new lifestyle or a new technology or a new computer is simply a manifestation of the human experience. If you know language, you know history, you know argumentation, you can write well, then, you can function in any new environment.

That’s the only constant that can prepare you. The same thing if you come to class on time, if you turn a paper in on time, if you don’t plagiarize, if you play by a particular convention or rule, or law, then, whatever the change or situation puts you in China, puts you in Hong Kong, the same principles of success and well-being will apply. What I’m worried about is what I call the “sirens of presentism.”

You have 500 channels or you have a new desktop and you’ve faked yourself into believing that you don’t have to write anymore, computers will do it, or there’s a situational ethics that is a new morality, or there’s a moral equivalence. You really see it in Afghanistan where deliberately trying to blow somebody up in New York in a time of peace is the same as somebody dying when you’re deliberately trying to avoid killing civilians and killing the people who kill people in Afghanistan.

We’ve got to watch that. This utopian pacifism, moral equivalence, multiculturalism, no appreciation for the uniqueness of your culture, and general education, is what I would advise students.

Harry: On that note, Victor, I want to thank you for coming to the campus to lecture today and to be with us today, and sharing with us this very fascinating intellectual journey, thank you.

Victor: Well, thank you for having me.

Harry: Thank you very much for joining us for this Conversation with History.