Table of Contents

By the late 19th century, Nietzsche declared “God is dead”—a diagnosis of Christianity’s weakening authority in Europe, particularly that of the Catholic church. Fast forward to today: The church’s declining authority has been replaced, at least in part, with deference to another authority, that of “Science”—with a capital S, as we’ll explore below—because human nature hasn’t changed: We remain biased towards belief (or removing doubt).

As humans, we have a desperate need to believe in something, anything. This makes us eminently gullible: We simply cannot endure long periods of doubt, or of the emptiness that comes from a lack of something to believe in.

– Robert Greene, The 48 Laws of Power.

So while “God is dead” might be an apt description for the decline in the church’s authority, what has come to replace it? After all, it was the prospect of God’s death that terrified Nietzsche as it did Carl Jung, who famously observed, “You cannot take away a man’s gods without replacing them something else of equal value”—a sentiment echoed by Robert Greene’s comment above.

In Nietzsche’s case, he correctly foresaw the profound crisis of meaning that would follow the decline of traditional religious frameworks in the modern world. Both Jung and Nietzsche, in their own ways, predicted that the psychological and societal void created by God’s death would lead to a collapse in foundational belief systems. This is a key part of what Jordan Peterson talks about and is why, in his estimation, in the wake of God’s death we saw the rise of totalitarian ideologies like Communism and National Socialism in the 20th century. They filled the church’s void. Nowadays, that same void has been filled by Science and its brethren (ex: global warming aka climate change) along with a host of other pseudo-religious movements combining Eastern philosophy with Western psychology.

In this essay, we’re going to tie together the collapse in the belief of the traditional, Judeo-Christian God of Western civilization to the subsequent rise of Scientism. To begin with, let’s define a few terms:

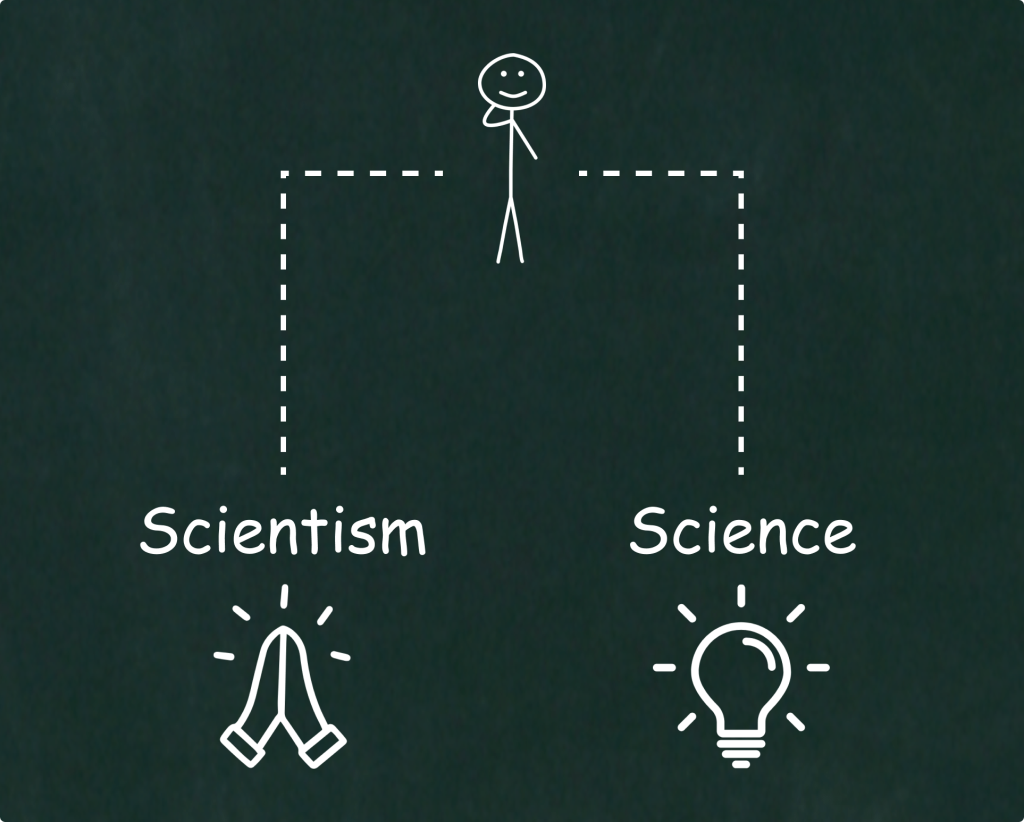

- Small-s “science” is a method of inquiry; it’s a process centered on asking questions and testing one’s hypothesis to find a valid theory.

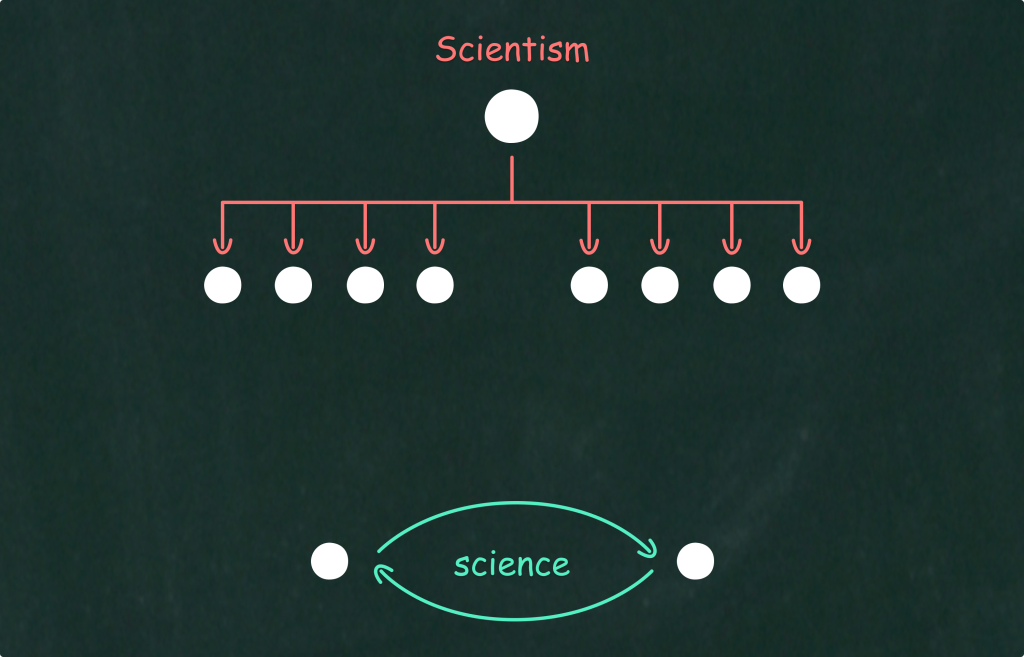

- Capital-S “Science” or “Scientism” is a belief system by which people organize their lives and which relies on authority bias; it prioritizes certainty and consensus over inquiry—the very antithesis of science and truth-seeking.

This distinction between Science (aka Scientism) and science matters because while science is a precursor to technological progress, Scientism leads to stasis and can be very dangerous because it promotes the illusion of knowledge rather than real knowledge.

The greatest enemy of knowledge is not ignorance, it is the illusion of knowledge.

– Stephen Hawking

What Is Scientism and Why It’s a Dangerous Belief System

Have you ever been in a discussion with someone and, when you question their assertions, they appeal to authority to justify what they’ve said? Sometimes this sounds like citing a scientific study to “prove” their point and, when you express doubt, they attack your identity rather than address the logic and evidence behind your question. They treat your skepticism as cynicism and proof that you’re a non-believer. One of the unenlightened who hasn’t been anointed. One of the dangerous ones. Sound familiar?

Scientism: the belief that science looks…like science, with too much emphasis on the cosmetic aspects, rather than its skeptical machinery. It prevails in domains with administrators judging contributions according to metrics. It also prevails in domains left to people who talk about science without “doing,” such as journalists and schoolteachers.

– Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Skin in the Game.

If you want a taste of Scientism (or Science with capital S), just imagine yourself being a student in the following classroom scene:

The next week Phaedrus had read the material and was prepared to take apart the statement that rhetoric is an art because it can be reduced to a rational system of order. By this criterion General Motors produced pure art, whereas Picasso did not. If there were deeper meanings to Aristotle than met the eye this would be as good a place as any to make them visible.

But the question never got raised. Phaedrus put up his hand to do so, caught a microsecond flash of malice from the teacher’s eye, but then another student said, almost as an interruption, “I think there are some very dubious statements here.”

That was all he got out.

“Sir, we are not here to learn what you think!” hissed the Professor of Philosophy. Like acid. “We are here to learn what Aristotle thinks!” Straight in the face. “When we wish to learn what you think we will assign a course in the subject!”

Silence. The student is stunned. So is everyone else.

But the Professor of Philosophy is not done. He points his finger at the student and demands, “According to Aristotle: What are the three kinds of particular rhetoric according to subject matter discussed?”

More silence. The student doesn’t know. “Then you haven’t read it, have you?”

– Robert Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry Into Values.

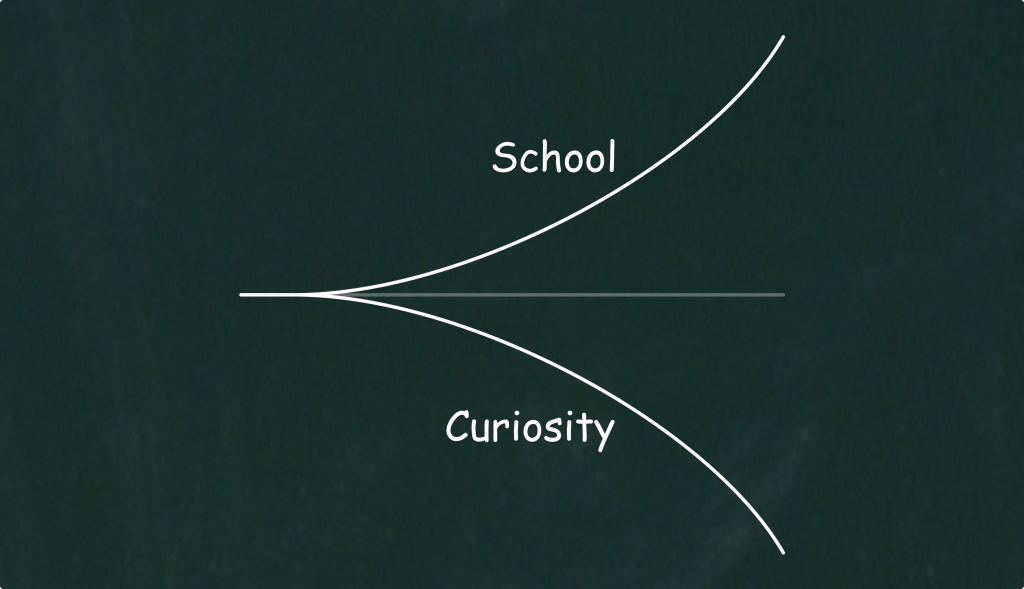

It’s really sad how the traditional, government-led educational system methodically works to kill our curiosity, training us to become obedient, disciplined dogs who accept ideas solely on the basis of authority—even when those ideas are ludicrous.

School was pretty hard for me at the beginning. My mother taught me how to read before I got to school, and so when I got there I really just wanted to do two things: I wanted to read books, because I loved reading books, and I wanted to go outside and chase butterflies. You know, do the things that five-year-olds like to do. I encountered authority of a different kind than I had ever encountered before, and I did not like it. And they really almost got me. They came this close to really beating any curiosity out of me.

– Steve Jobs, Make Something Wonderful.

At the core of any belief system, Scientism included, is the promise of certainty and the removal of doubt. That also strongly appeals to us: Certainty feels more comfortable than uncertainty.

This not only kneecaps the purpose of science—to ask skeptical questions and test one’s theories—but it can also be dangerous. When you feel certain of something you don’t actually understand, you become overconfident and make decisions that might harm you or others. That’s why ignorance is better than the illusion of knowledge: If you know you are ignorant, then you will at least act with caution.

In his book The Elon Musk Blog Series: Wait but Why, Tim Urban makes an excellent distinction between dogma and science:

The flood geologists of the 17th and 18th centuries weren’t stupid. And they weren’t anti-science. Many of them were just as accomplished in their fields as their science geologist colleagues.

But they were victims—victims of a religious dogma they were told to believe without question. The recipe they followed was scripture, a recipe that turned out to be wrong. And as a result, they proceeded on their path with a fatal flaw in their thinking—a software bug that told them that one of the undeniable first principles when thinking about the Earth was that it began 6,000 years ago and that there had been a flood of the most epic proportions.

With that software bug in place, all further computations were moot. Any reasoning tree that puzzled upwards with those assumptions at its root had no chance of finding truth.

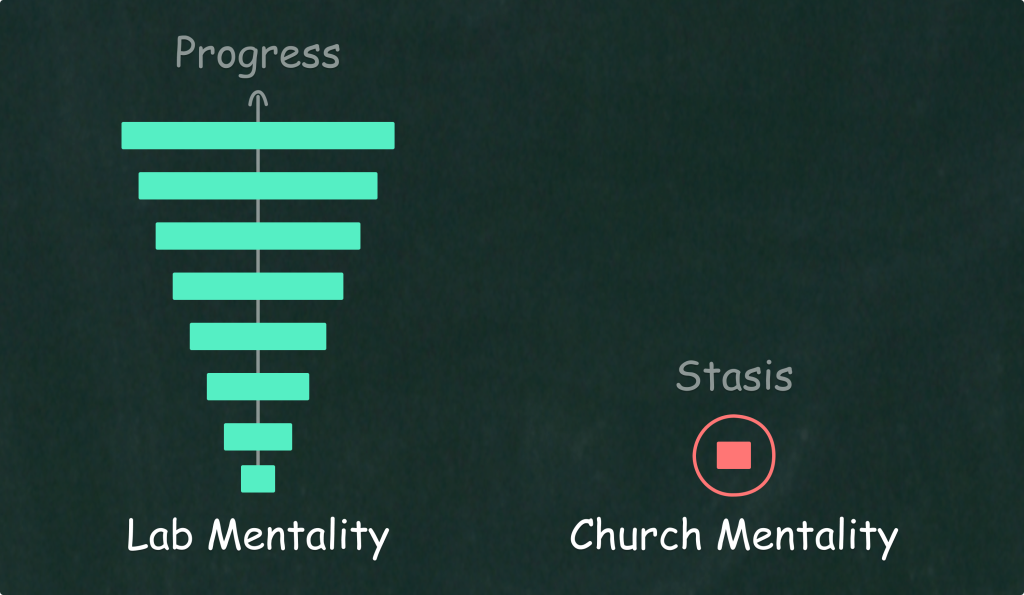

Even more than being victims of any dogma, the flood geologists were victims of their own certainty. Without certainty, dogma has no power. And when data is required in order to believe something, false dogma has no legs to stand on. It wasn’t the church dogma that hindered the flood geologists, it was the church mentality of faith-based certainty.

That’s what Stephen Hawking meant when he said, “The greatest enemy of knowledge is not ignorance, it is the illusion of knowledge.” Neither the science geologist nor the flood geologist started off with knowledge. But what gave the science geologist the power to seek out the truth was knowing that he lacked knowledge. The science geologists subscribed to the lab mentality, which starts by saying “I don’t know shit” and works upwards from there.

If you want to see the lab mentality at work, just search for famous quotes of any prominent scientist and you’ll see each one of them expressing the fact that they don’t know shit.

Here’s Isaac Newton: To myself I am only a child playing on the beach, while vast oceans of truth lie undiscovered before me.

And Richard Feynman: I was born not knowing and have had only a little time to change that here and there.

And Niels Bohr: Every sentence I utter must be understood not as an affirmation, but as a question.

[Elon] Musk has said his own version: You should take the approach that you’re wrong. Your goal is to be less wrong.

The reason these outrageously smart people are so humble about what they know is that as scientists, they’re aware that unjustified certainty is the bane of understanding and the death of effective reasoning. They firmly believe that reasoning of all kinds should take place in a lab, not a church.

In some cases, this “church mentality” is imposed systematically by authoritarian governments or entities that don’t tolerate criticism. By doing this, these institutions feel safer but they essentially destroy all freedom of speech—which is the bedrock of science, because it promotes criticism and error correction.

For Bhattacharya, the single thread tying all of this together is free inquiry:

“If you were a scientist in the Soviet Union during the time of Stalin, you’d have this guy named Trofim Lysenko who fundamentally believed that Mendelian genetics was false—in fact, that it was a capitalist plot. You were only allowed to agree with his theories. And so he used his position to suppress the speech of all the Mendelian geneticists around him. Many of them went to the gulag. As a result, science on agriculture basically froze and people were always starving as a consequence of this.”That lesson, he argues, applies directly to America today.

“You can’t have science unless you’re allowed to criticize the predominant ideas. And if you have scientific power married to political power in a way that suppresses the ability for lots and lots of other scientists to say, ‘Look, you’re wrong, here’s this experiment to prove it’—you don’t have science. You have something else.”

The True Nature of Science: A Method of Inquiry, Not a Belief System

Unlike Scientism, science is not a belief system but a method of inquiry. It’s about skepticism, questioning, and a willingness to test and verify. In essence, it’s about finding a demonstrable, provable, and repeatable truth. And to find this truth, one needs to:

1. Avoid being swindled by authorities and experts.

You should, in science, believe logic and arguments, carefully drawn, and not authorities.

– Richard Feynman

Science is more than a body of knowledge. It is a way of thinking; a way of skeptically interrogating the universe with a fine understanding of human fallibility.

If we are not able to ask skeptical questions, to interrogate those who tell us that something is true, to be skeptical of those in authority, then, we are up for grabs for the next charlatan (political or religious) who comes rambling along.– Carl Sagan

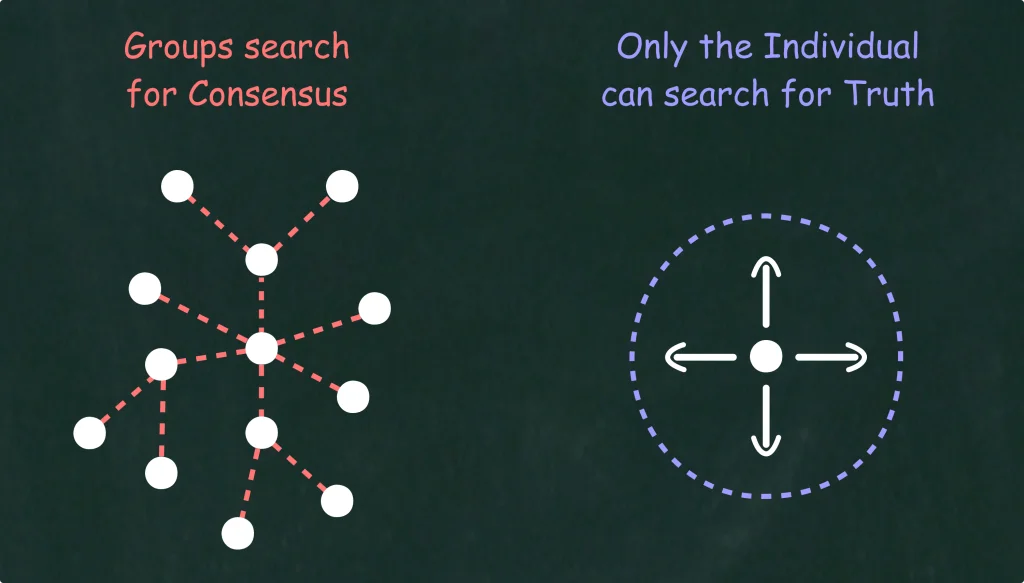

2. Resist groupthink—because groups search for consensus, not truth.

Our tendency to doubt, the distance that allows us to reason, is broken down when we join a group. The warmth and infectiousness of the group overwhelm the skeptical individual.

– Robert Greene, The 48 Laws of Power.

Naval Ravikant: [Richard Feynman] famously said that science is the belief in the ignorance of experts. And it’s so funny because these days, so many people are on Twitter [X] saying, “Believe in science,” or “According to science.” And you have to realize there’s no such thing as science with a capital S. The foundation of science is doubt. It is all about falsifiability.

David Deutsch, who’s kind of one of my current modern living physicist heroes, is a Popperian—he subscribes to Karl Popper’s philosophy. And he basically says that if it’s not falsifiable (if you can’t prove it’s false), it’s not scientific. If it’s true up or down or left or right, it’s not science.

[Science] doesn’t require belief, you should be able to challenge it at all times. It should make risky predictions that are not obvious, and those predictions should then be tested. And you shouldn’t be able to, after the fact, move the goalposts or change how the predictions were set up. And so those are the hallmarks of good science: falsifiability, independent verifiability, and making risky and narrow predictions with details that are hard to vary both before and after the fact. And that’s how you end up with good science and good explanations, not by people on Twitter voting—that’s politics.

Everything has become politics now; science has become politics, too. People are politicizing it. There’s “big science,” but I think Feynman would be very unhappy with that. He was a generally happy, non-political character, who tried not to get involved in these things. But I think he would realize that this isn’t actually science—it’s a masquerade of science. It’s almost becoming Social Science.

Nassim Taleb is one of my favorite people to follow on Twitter, even though he’s a bit…

Tim Ferriss: Cantankerous?

Naval Ravikant: Yeah. He’s cantankerous. He annoys people for sure. But if you want to hear the truth, you gotta be prepared to be hurt a little bit. He had a great tweet recently that I retweeted, which I’m sure made a lot of people mad. He said: “The opposite of education is not ignorance. The opposite of education is an education in Social Science.” I thought that was hilarious. It hurts because there’s some truth to it. If there was no truth to it, it wouldn’t hurt at all. If I said, “Tim Ferriss is fat,” that would just bounce right off you. But if I said, “Tim Ferriss and Naval are fake gurus,” that might hit us, right? Because deep down, we might suspect there’s a part of that that’s true. It’s the same with Social Science—it does lead you down the road to ignorance, because it’s about the social. And anything social is about groupthink and group behavior.

Individuals can search for truth, but groups search for consensus. If a group doesn’t have consensus, it can’t get along. If it can’t get along, it falls apart, and then there’s conflict. So the last place you’re going to find truth is in large groups. And the moment you make science about large groups, about voting, about consensus—you’re not really practicing science anymore.

– Naval Ravikant (Interview with Tim Ferriss)

Beyond the effects of technological progress and a deeper understanding of the world, the practice of science also has a sublime effect on the human spirit:

The most beautiful emotion we can experience is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion that stands at the cradle of all true art and science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead, a snuffed-out candle. To sense that behind anything that can be experienced there is something that our minds cannot grasp, whose beauty and sublimity reaches us only indirectly: this is religiousness. In this sense, and in this sense only, I am a devoutly religious man.

– Albert Einstein, Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson.

Scientism vs. Science: Key Differences and Implications for Society

Ironically, you defeat Scientism by embodying the elemental characteristic of science: curiosity and skepticism. Doing so might annoy some people. They might even ostracize you for questioning what “everyone knows to be true”—so be careful when you publicly do so. Yet as Nietzsche said: “No price is too high to pay for the privilege of owning yourself.”

At the same time, you don’t want to quarrel with close-minded people. The kind who feel that all their ideas are “settled facts” and objectively true, and even identify personally with these ideas so that any debate feels like a personal attack, which defeats the purpose of debating. These types of debates, and perhaps even these types of people, are not worth your time and energy. In this case, you can put on a façade of going along with their claims, but internally you preserve your independence of thought. This is one of Robert Greene’s laws of power: “Think as you like but behave like others.”

Bene vixit, qui bene latuit—”He lives well who conceals himself well.”

– Ovid.

If, on the other hand, you sense the other person is well-intentioned, open-minded, and willing to explore different perspectives (even if it contradicts what they believe), by all means debate with them. Especially when they disagree with you. As Noah Kagan put it: “If there’s not fighting, you’re not getting the best ideas.” That is ultimately what science is all about: testing one’s ideas and hypotheses to find out what is demonstrably true.

If You Liked This Essay, Check Out These Sources

- The 48 Laws of Power, by Robert Greene

- Wisdom vs. Knowledge: How To Guarantee Success In The Digital Age

- Skepticism vs. Cynicism: The Mindshift That Will Change Your Life

- Skin in the Game, by Nassim Nicholas Taleb

- Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry Into Values, by Robert Pirsig

- Make Something Wonderful, by Steve Jobs

- The Elon Musk Blog Series: Wait but Why, by Tim Urban

- Naval Ravikant on Happiness, Anxiety, and More

- Einstein: His Life and Universe, by Walter Isaacson