Table of Contents

Jonathan Haidt is an award-winning author and a professor at NYU’s Stern School of Business. He’s the man behind The Happiness Hypothesis (an excellent book combining philosophical wisdom and scientific research!) and the NY Times bestsellers The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion and The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure (with Greg Lukianoff). His latest book is The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness.

This 2018 presentation of Haidt’s at Penn State looks at how “play-based childhood” began to decline in the 1980s and how it’s been finally wiped out by the arrival of the “phone-based childhood” in the early 2010s. Haidt has been studying the contributions of social media to the decline of teen mental health and the rise of political dysfunction. He explains why social media damages girls more than boys and why boys have been withdrawing from the real world into the virtual world, with disastrous consequences for themselves, their families, and their societies. As Haidt conclusively argues, we’ve overprotected our children from the real world and under-protected them from the virtual world.

Enjoy!

Jonathan Haidt: I actually have a long history with Penn State because my first academic job interview was here in 1994. I didn’t get the job but eight years later I married a local girl and sort of married into Penn State.

My wife, Jayne Riew, grew up here because her father, John Riew, has been teaching in the Economics Department since 1963, the year that I was born. While he’s retired from teaching, he still goes to the office. He still serves Penn State every year on recruiting trips for the Economics Department. I see from his loyalty to the University, the love that the family has for Penn State, the insane fandom of this university, and the loyalty that it breeds that this is an amazing place.

I had a great conversation with some of your top students this afternoon. It looks as though this speech climate, a lot of the problems that I’m talking about here today are not nearly as bad here as they are in many of your peer institutions and many of our top universities in the country, but it’s a pleasure to be here at Penn State talking to you about these things. [unintelligible 00:07:04] If you would stand up for a moment and have the community recognize you for your 55 years of service.

The Unique Challenges Facing American Universities

We Americans have strong feelings about our universities because our universities are different from anyone else’s in the world. Our top ones are modeled on Oxford and Cambridge, and we have this idea of an idyllic time on the quad.

Now, in British universities, you can’t actually go on the grass; they never actually let you touch the grass. But in American universities, we know we have these beautiful campuses, and a lot of our memories are about times on the campus. We’re much more sociable and intense than most European universities.

I just found this online the other day. I think it was just in the last week or something. I don’t know what it is, but I’m sure it brings back memories for some of you. We have these really strong feelings. We love our universities, but what’s happening now is that we’re all trying to do university while two mega-trends are making it much harder.

They’re interfering with what we do on campus. They’re interfering with many institutions in American society.

I’d like to begin by talking about these two mega-trends.

One is the mental health crisis, and the other is polarization.

Here is what is happening. Who do we have here in the audience?

Raise your hand if you are a current Penn State student. How many Penn State students? Okay, great. The majority.

Raise your hand if you are a professor at Penn State. Okay, a lot. Great.

Raise your hand if you’re an administrator of any sort. Okay, administrators, I’m so sorry about your jobs. You have the toughest work on the university.

I’ll try to explain why your job has gotten harder in recent years.

This is one of the reasons.

Everywhere I go, all across the country, anybody working with teenagers or young adults says the same thing, that there’s been a surge in the rate of anxiety and depression, every campus mental health center is overwhelmed, and they can’t hire therapists fast enough. Something is going on.

It’s not just anecdotes; there’s lots of reportage around it, but as you dig into the statistics, what you see is something truly scary. First, we have to understand that college students today are not Millennials. They are Gen Z.

Distinctions Between Millennials and Gen Z

Most of us, until two years ago, thought that the Millennials were people born from 1982 to around 2000, maybe 1998. Now, it’s clear that kids born in 1995 — or six or seven, depending on how you count it — had a different childhood and turned out differently than the Millennials.

Here’s what we see about them.

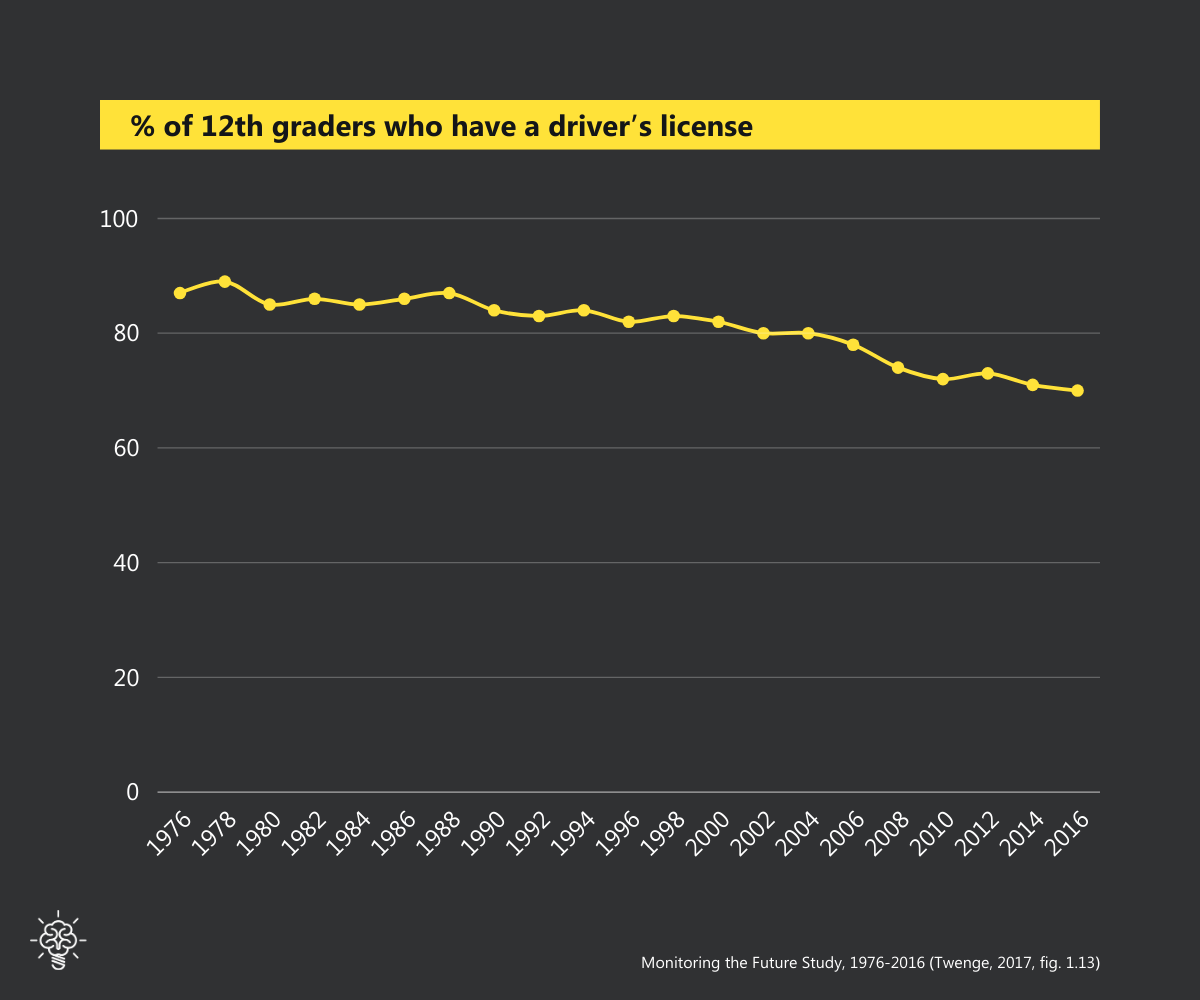

This is from Jean Twenge’s work, but I’ll show other work. There’s a lot that validates it. This shows the rates at which teenage Americans hit certain milestones or engage in certain kinds of behaviors. One is that this is the percentage of 12th graders who have a driver’s license.

Now, those of you who are older than 40 you’re thinking, “What do you mean?”

If the DMV is closed on your birthday when you’re 16, you have to wait till Monday, but why would you ever wait till Tuesday to get your license, but nowadays a lot of kids don’t even bother to get one.

They don’t care. They don’t need one.

They’re not going out very much because, for one thing, many of them have never drunk alcohol, gone out on a date, or had a job for pay.

If you’re not doing any of these things, you don’t really need a car. If you’re not doing any of these things, what are you doing? Young people call it out. What are teenagers doing more of that wasn’t done before? What?

Audience: Video games.

Impact of Social Media on Adolescent Development

Jonathan: Video games, that’s right. For the boys, video games, for the girls, social media is what fills up a lot of their time.

Basically, devices.

Gen Z got these really intense, amazing, wonderful devices in middle school or earlier, whereas the millennials didn’t get them until college or later.

That, we think is one of the main reasons for the generational difference.

Here’s what has been the results.

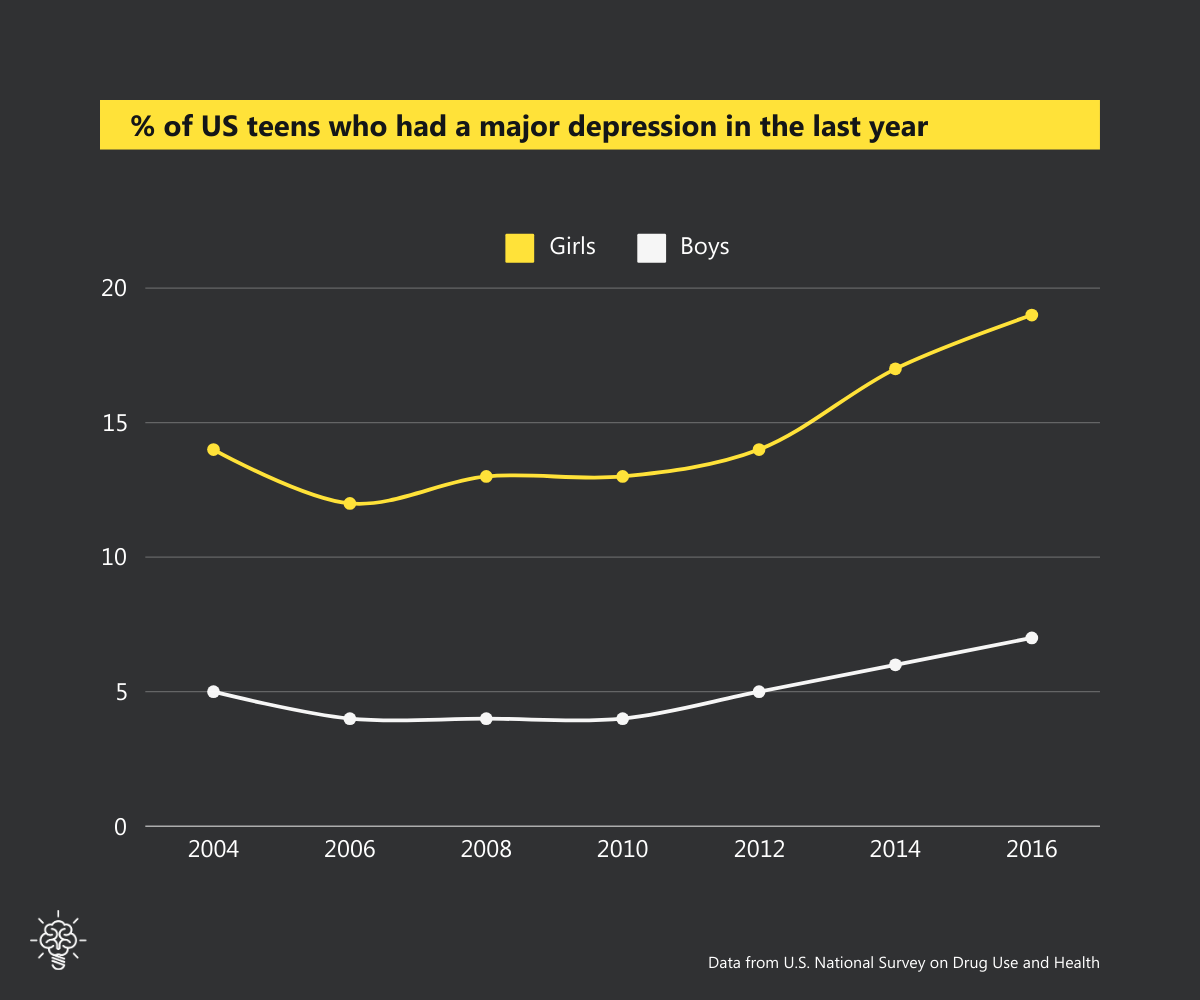

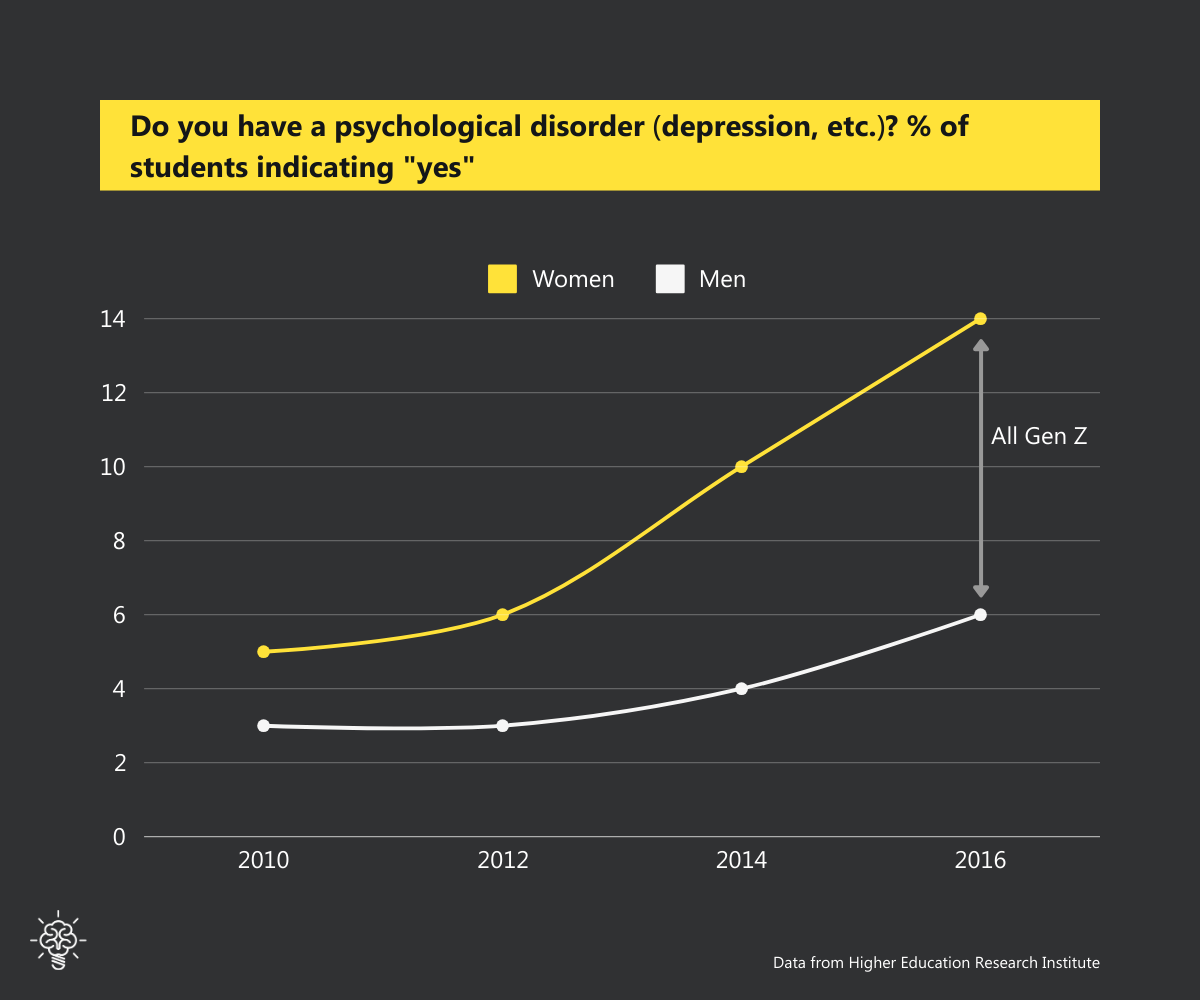

If we look at rates of major depression, these are teenagers who said yes to five out of nine symptoms on a symptom checklist, what we see is that from 2004 to 2010 the rates were fairly constant.

Girls have higher rates of depression and anxiety, boys have higher rates of alcoholism, violence, things that make other people miserable. What we see is that when Gen Z enters the picture, the rate for boys does go up as a percentage that actually is a substantial increase, but clearly, it’s affected girls more.

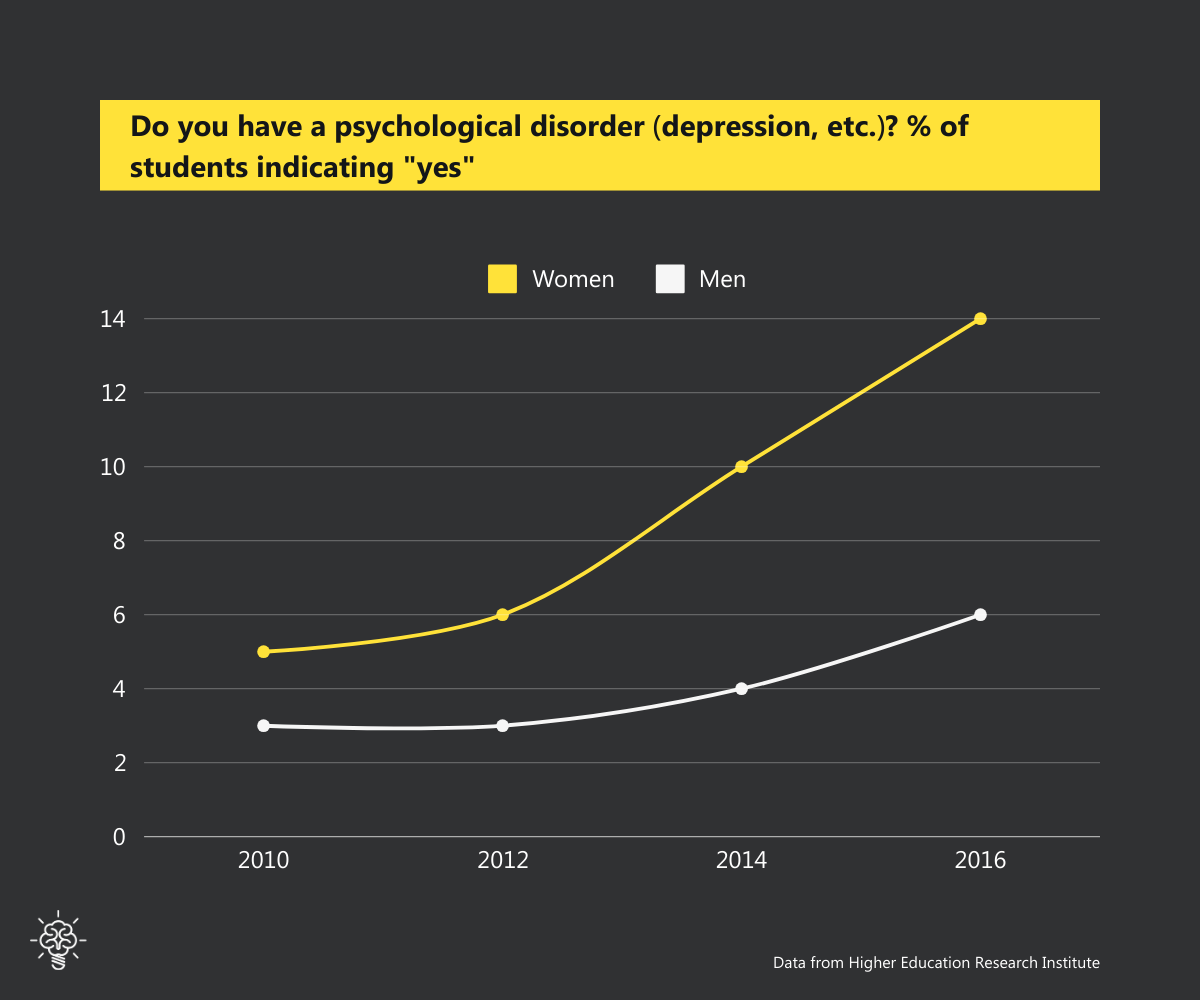

The rates of depression and anxiety have gone way up for girls and more moderately up for boys. When we look just on college campuses, just college students representative survey, what we see is that in 2012, when everybody on campus was a millennial, the percentage of students who said yes they have a psychological disorder, it was up to them to label it. But, the percentage who self-identify as having a psychological disorder was very low for women and men. Still, once the millennials leave and now college is all Gen Z other than veterans or older people coming back but the ones who are coming out of high school, they have much, much higher rates of believing that they have a mental disorder, and it’s mostly depression and anxiety.

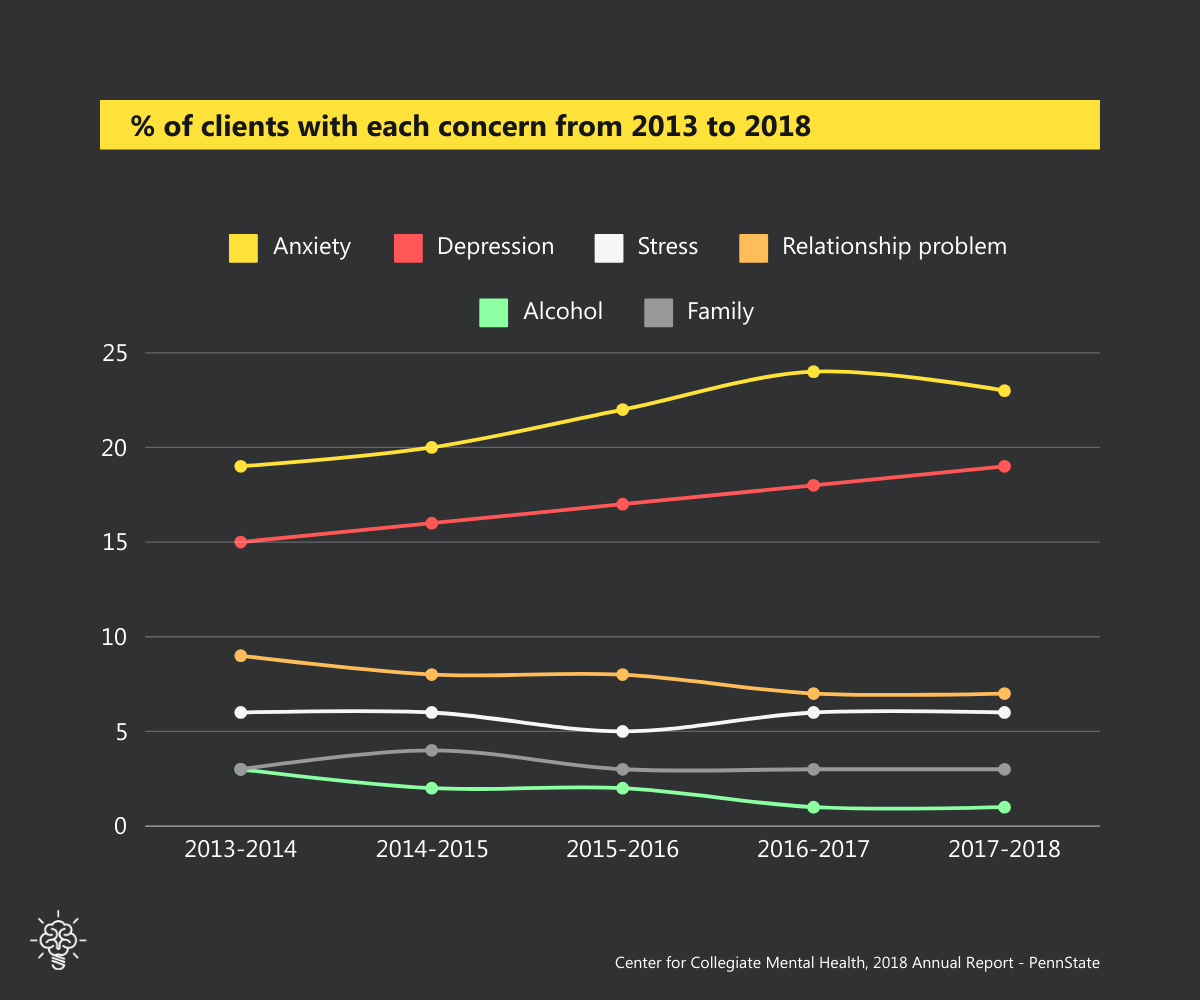

Some great work done here at Penn State. You have an institute that collects information from all the counseling centers around the country.

Why are so many students going to the counseling center?

What is the reason that they report when they come in through the front door?

The reason as you can see going back to 2013, 2014 to the present, the only things that are going up are anxiety and depression, nothing else is rising.

It’s not that young people today are just so comfortable talking about it, “I’ve schizophrenia, I’ve bipolar disorder,” no, it’s only depression and anxiety. It’s not even stress.

Gen Z does not claim to be more stressed than a previous generation. They just never got the chance to learn how to deal with normal, ordinary, everyday stress. I’ll explain why later.

As I mentioned there is some skepticism, this is with The New York Times a few months ago, Richard Friedman saying, “Relax, there is no epidemic and there’s no harm caused by devices.

Your kids playing video games, your kids spending hours and hours a day on devices, relax.

The only evidence that it’s harming them is self-report. These surveys that show that they say that they’re more depressed, but they’re just more comfortable talking about it.”

That’s his argument in The New York Times, but I believe that he is wrong. Here’s why.

The Phenomenon of Rising Self-Harm and Suicide Rates

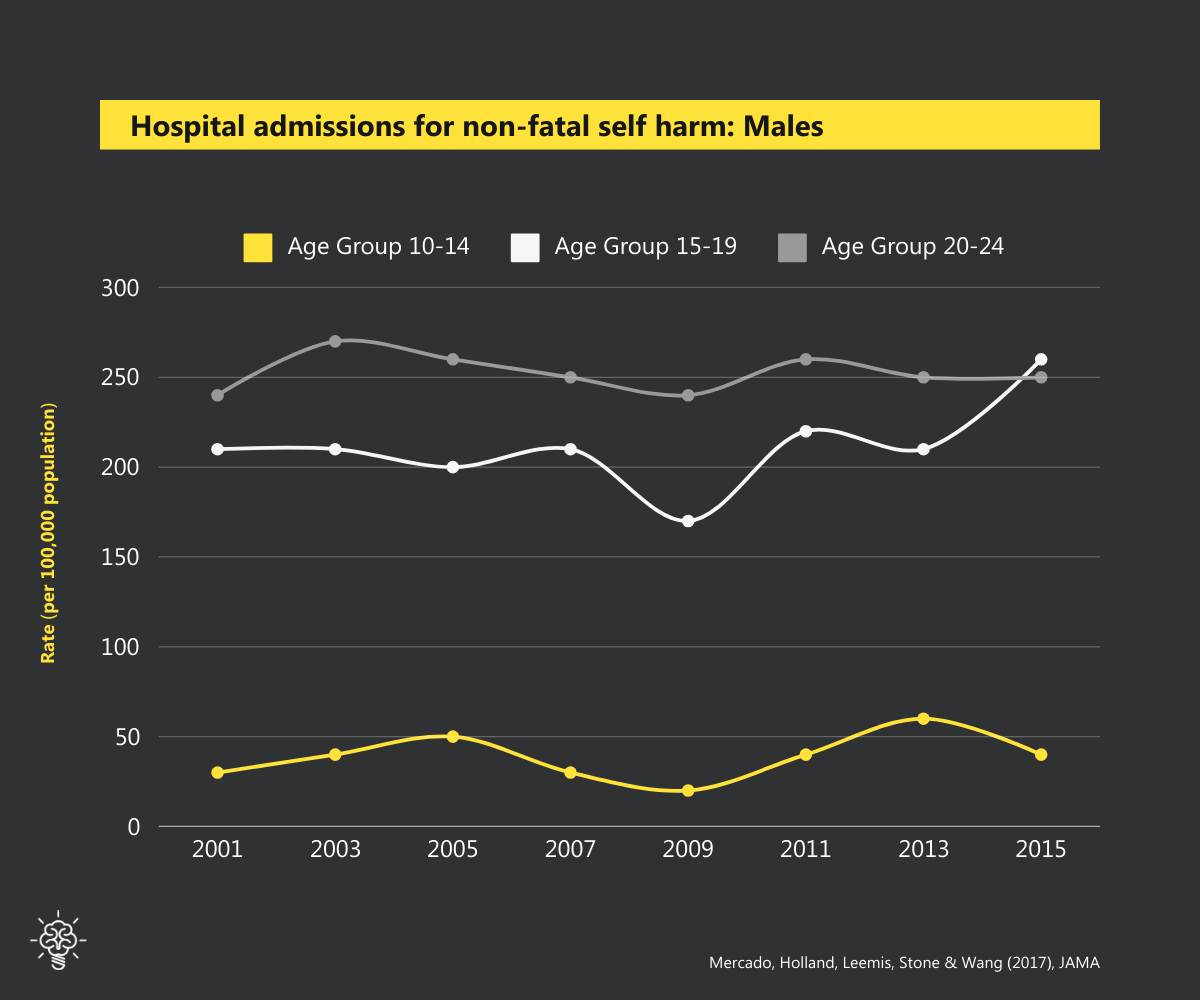

This is data on the percentage of boys, now for boys there is no change but this is data on the number of boys out of 100,000 in the population who are admitted to a hospital each year for cutting themselves or otherwise harming themselves so severely that they required hospitalization.

As you see, the youngest boys aged 10 to 14 almost never do that. The rates are low for boys compared to the girls, which you’ll see in a moment.

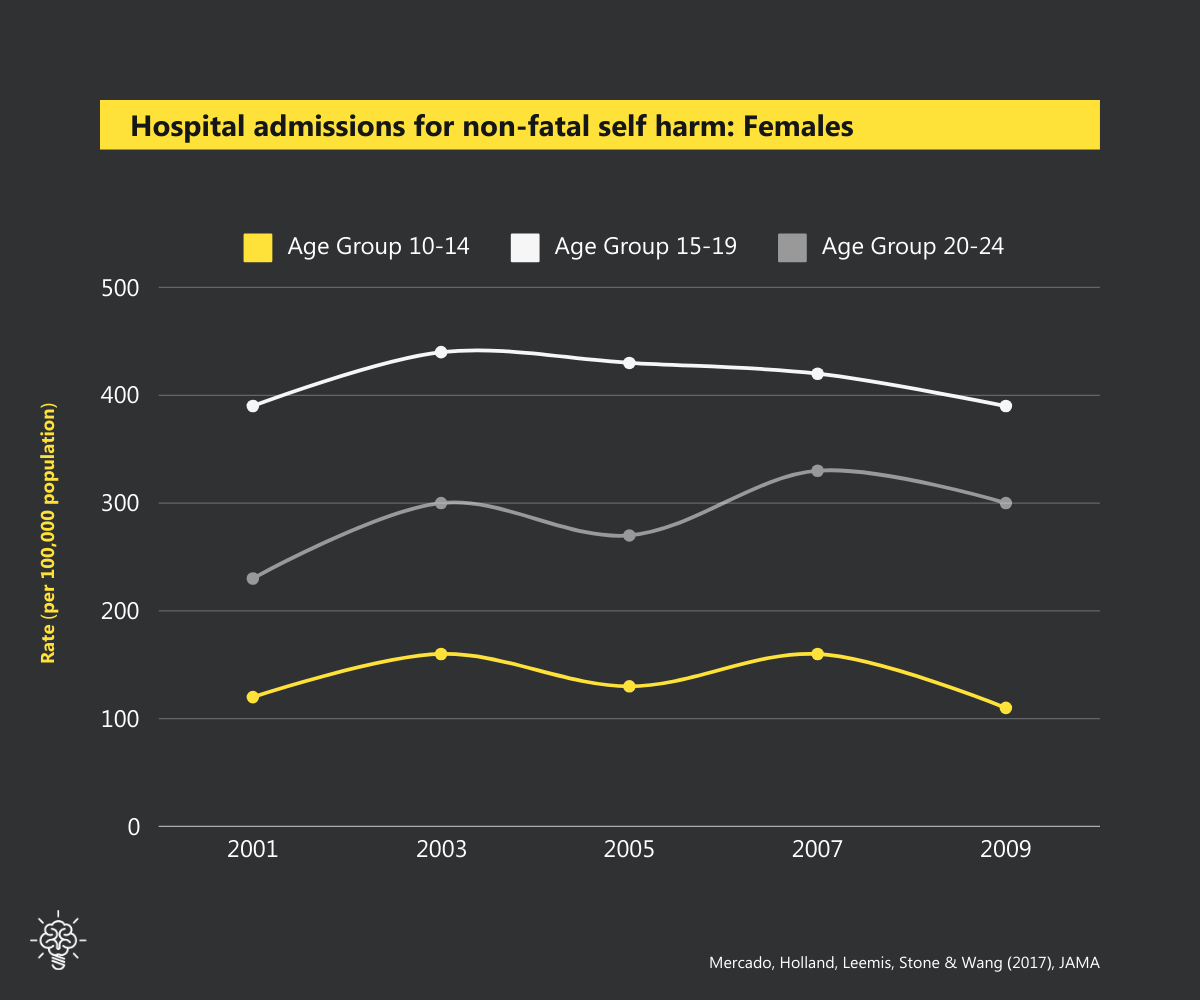

For boys, there’s been no change as we go from 2001 to 2015 but look at the rates for girls, much, much higher.

Now, here I’ve cut it off at 2009, much, much higher.

This is a manifestation of an anxiety disorder. Self-harm is a product of anxiety disorders. Much higher rates for girls and young women as you see, but look what happens after 2009.

What you see is that for older teenage girls, the rate has increased by 62%.

This is not self-report, this is not just changing diagnostic criteria, these are hospital admissions.

Now, interestingly, the oldest group here, the millennials, in this data set, were not affected because, as I said, they got social media when they were in college and later, and there’s not much evidence that it was harmful in college.

I believe — I’m working on a lit review now — there’s debate about this, but my conclusion from going through the data is that the problem is using social media in middle school, and that’s a problem, especially for girls.

Look what happens to the youngest girls, aged 10 to 14. They didn’t use to cut themselves, but their rate has gone up 189% since they got social media in middle school.

Again, I can’t prove causality, but I have a lit review online, which I’m working on, which is available. I think the evidence does point to social media as being the reason for the huge sex difference in what has happened to teenagers. It also shows up in suicide.

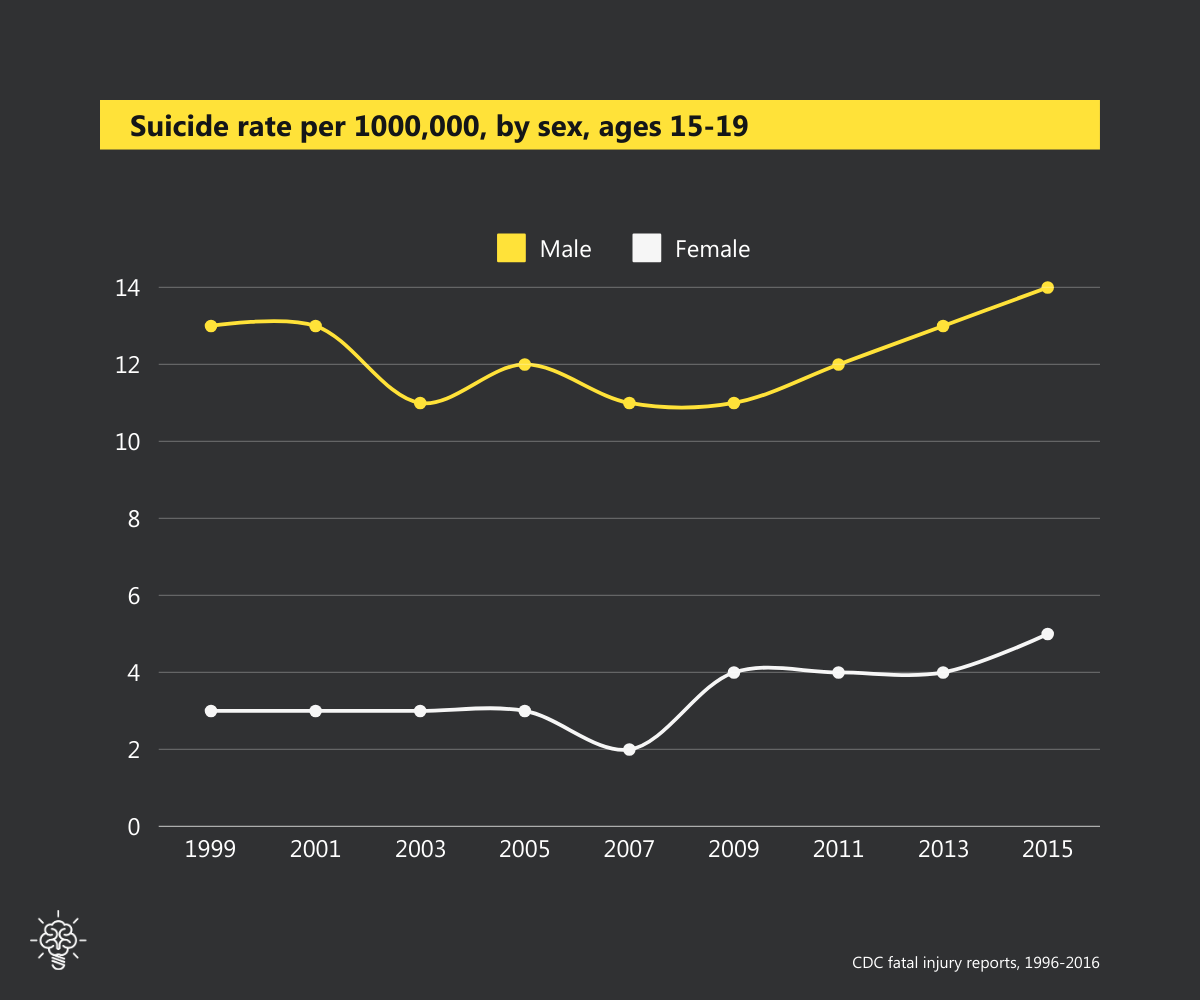

The suicide rate was higher for males in the ’80s and ’90s when there was a huge crime wave and a lot of violence, but it’s been stable in the 2000s until recently. For males, it’s up 25%.

It turns out most age groups in America are going up. Suicide is going down around the world, but it’s going up in America for almost all age groups both sexes. The rise for boys is actually not much more than what’s happening to older men.

The rise for women, while it’s higher than for men overall, for 15 to 19-year-old girls, it’s up 70%, which is much higher.

For 10 to 14-year-old girls, we have a very low base rate, but for them again, the increase is gigantic, a 151% increase in pre-teen girl suicides in this country.

Something is going wrong, especially for girls. 2015 hit a peak higher than ever recorded since we’ve been collecting data, and two years after that are right about the same level.

It was not a one-year spike.

That’s the first mega-trend. This affects a lot of things on campus. This is affecting companies, corporations who are beginning to hire Gen Z and are noticing now that they have a lot more anxiety in their young employees. HR departments have to stuff up.

Political Polarization: A Growing Divide

The second trend I want to talk about is political polarization.

About 10 or 15 years ago, there was a debate as to whether America was becoming more polarized. Everybody agreed that we had elite polarization.

If you look at Congress, if you look at the media, if you look at the intellectual leaders those who are in the fray, everybody agreed that in the ’80s and ’90s we had elite polarization.

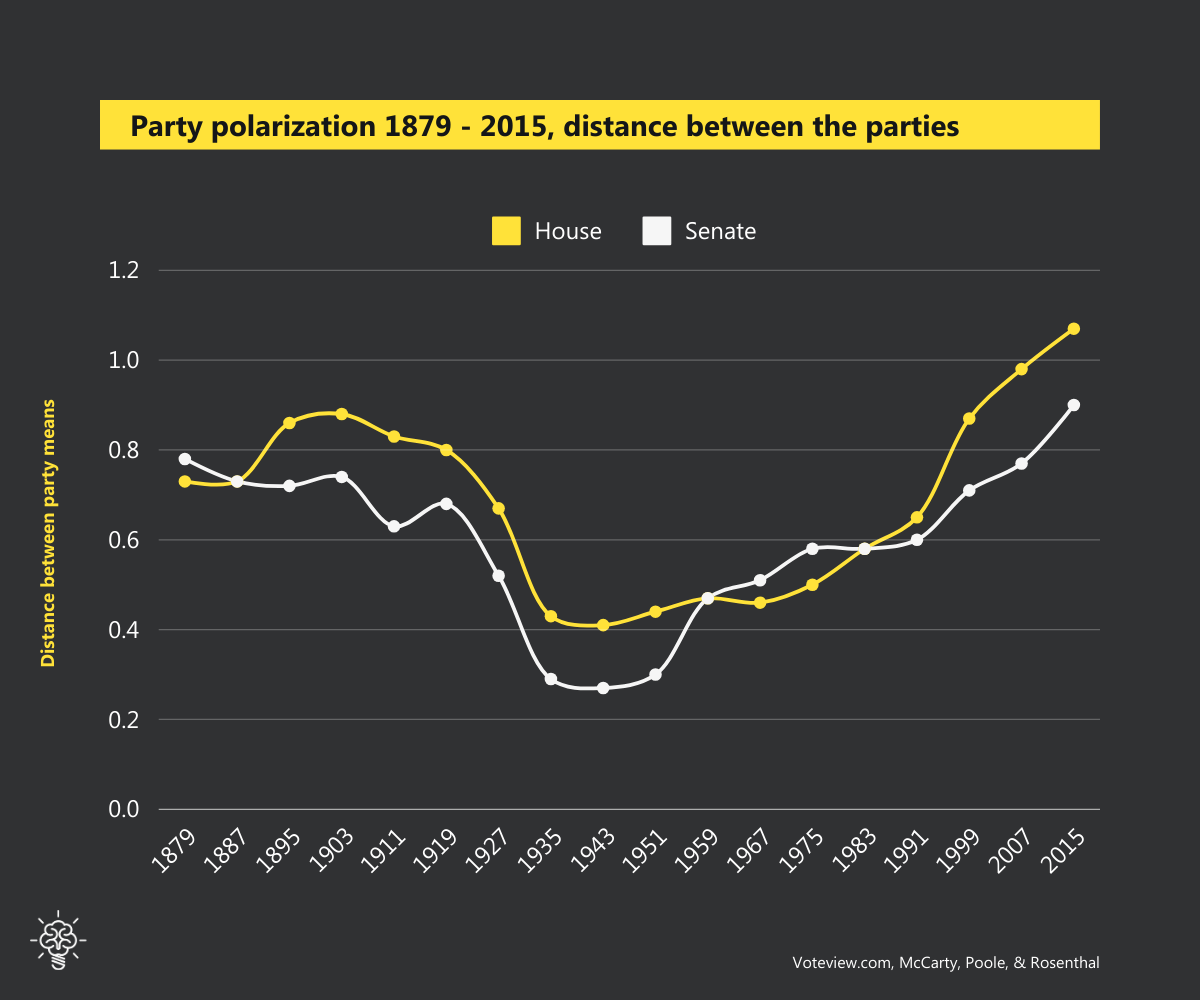

What you see here is the degree to which the US Congress is polarized going back to 1880. This is a calculation, to what extent can you predict everything about major votes? If all you know is where a particular legislature is on the left-right spectrum, if that allows you to predict, and then you can predict the two parties are far apart, then Congress is very polarized, just like straight-party voting on a left-right dimension.

In the wake of the Civil War, it was horribly polarized.

Then, for a variety of reasons, it plummets in the mid-20th century, and we have this period of very low polarization where there’s a lot of bipartisanship. There are many reasons for that, but what I want to point out is that that was an anomaly.

It was a temporary period, and what’s happened since the 1980s is this: The US Congress is more polarized than it has ever been, or at least it’s at the level that it was right after the Civil War.

It’s dysfunctional. It’s very hard to reform. It is ineffective as a legislature.

That’s elite polarization.

It’s also now clear, I think, the argument is settled that we also have mass polarization. If you keep your eye on especially what we think about each other, how much we hate each other.

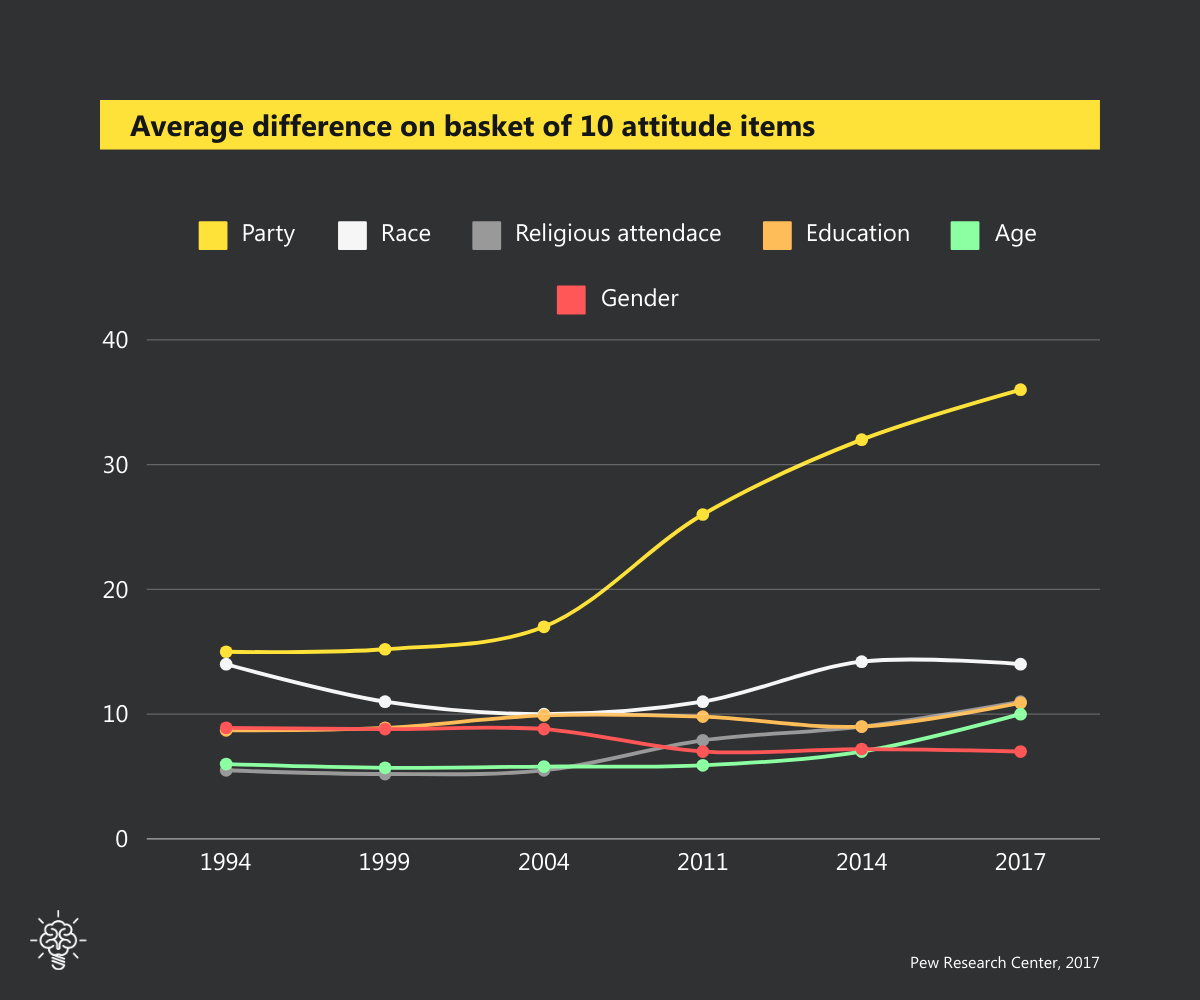

Even if you look at what we think about the issues where it’s harder to see, Pew has been studying American attitudes on a whole bunch of items.

They were able to go back to 1994 and look at to what extent are different demographic groups different on their attitudes to these issues and here’s what they find. The way to read this is — let’s look at gender.

If you take this basket of 10 items and you take the absolute value of the difference between males and females back in 1994 on this basket of items by gender, it was eight or nine points apart, and now it’s seven points apart.

On gender, there’s been no change.

Men and women are not further apart on this basket of issues.

If you look at religious attendance, it’s 11 points apart now. It used to be only five points apart.

Americans are now twice as far apart.

We are coming apart by religious attendance. If you know whether someone goes to church regularly you can predict something about their attitudes.

That increase is nothing compared to what has happened to our polarization by party. I forgot to click before to get you through there. Let’s wait. Here we go. This is what has happened to us by party.

Most of this, as you see, is just since around 2004. Polarization has been rising since the 1980s, but it is really rising in the last 10 or 15 years. Something is happening that is very, very bad for our democracy, for our ability to work together, trust each other compromise.

Why is this happening?

I wrote an article with a political scientist, Sam Abrams. I won’t go into these reasons. My point is there are a lot of historical trends. The late 20th century was an anomaly in a sense we had a lot of things going for us.

We took it for granted.

We thought democracy was easy.

We thought now the Soviet Union has collapsed, clearly this is the end of history.

All societies, as they develop, will become like the United States, or like Sweden, or some Western democracy. We thought it was easy. We took it for granted.

We were wrong.

Most of these trends cannot be reversed.

It doesn’t mean that things are hopeless. It just means it’s going to be really, really hard to turn this thing around.

Passions really rose, especially in 2016 and 2017. This is now where we come back to campus.

There was a huge rise in shout-downs and anticipations, all sorts of things happening in the 2016-2017 academic year. The president’s inauguration was actually a spurt that still raised the temperature on campus especially, and so while there’s been, thank God, very little violence on campus, most of the real violence occurred in the few months after the inauguration, when passions were very high.

The bloodiest event was at UC Berkeley. A lot of people were injured. It is incredible no one was killed. We tell the story in the book The Coddling of the American Mind. It’s amazing how many people were injured without being killed. That was Berkeley.

At Middlebury was another of these spectacular cases where a professor was assaulted. She was accompanying Charles Murray. That’s Charles Murray on the front. They wouldn’t let him speak, and when he and the other professor tried to leave the building, they were attacked.

She has a concussion and possibly permanent neck damage as well. There’s been a wave of activism of students who, especially in the last couple years, think that they can go into classes and shout in protest to shut things down if they object to what is happening.

There was a lot of that from 2015 to 2017. It declined quite a lot in 2018. At least of those shout-downs, and the violence is way down, thankfully, in the last year.

It has left in its wake a new moral and political culture on many campuses, and that’s what our book is about.

That’s what I mostly want to talk to you about.

What has happened is that just since 2014, we’ve seen the emergence on many campuses. It’s not very much here, but it’s at most liberal arts schools in the Northeast and the West Coast.

It’s scattered around the whole country, but what is this new culture that we call a culture of safety-ism?

It’s an idea that students think of themselves and people as very, very fragile. They see the world and the campus as very, very dangerous, and therefore, they need protection from words or violence and from certain kinds of words, books, speakers, and ideas.

If you see on many campuses in America, you do see, if you see a bunch of these terms together, they always travel together.

If people are talking about safe spaces, trigger warnings, micro-aggressions, and Bias Response Teams, America is a matrix of oppression. You get a call-out culture, and it’s often focused on single words. There’s a real reactivity to a single word. These are the features of this new moral culture.

What I’d like to do is analyze that for you.

That’s what our book is about with the great Lukianoff.

Why it happened suddenly, why it came out of nowhere in 2017.

Again, I won’t go through all the reasons. I’d like to make a list of reasons.

I’m a social scientist.

Everything’s complicated, and everything has multiple causal threads. Political polarization and rising anxiety are the two that I’m talking to you about, but a lot is because of the way we changed our child-rearing in the 1990s, and I’ll come back to that in a moment.

In the rest of my talk, now, I hope that this talk will be useful to Penn State students. I hope that this will help you navigate these meta-trends, both here on campus and when you graduate and go out into the working world.

I hope that this talk will be useful to Penn State professors and administrators.

The student body is changing, times are changing, all sorts of things are changing, and a lot of us don’t know what to do.

We end up being caught like deer in the headlights and implementing policies that are not based on research. I hope that the things here and the things in the book will help ground in empirically grounded reforms and policies.

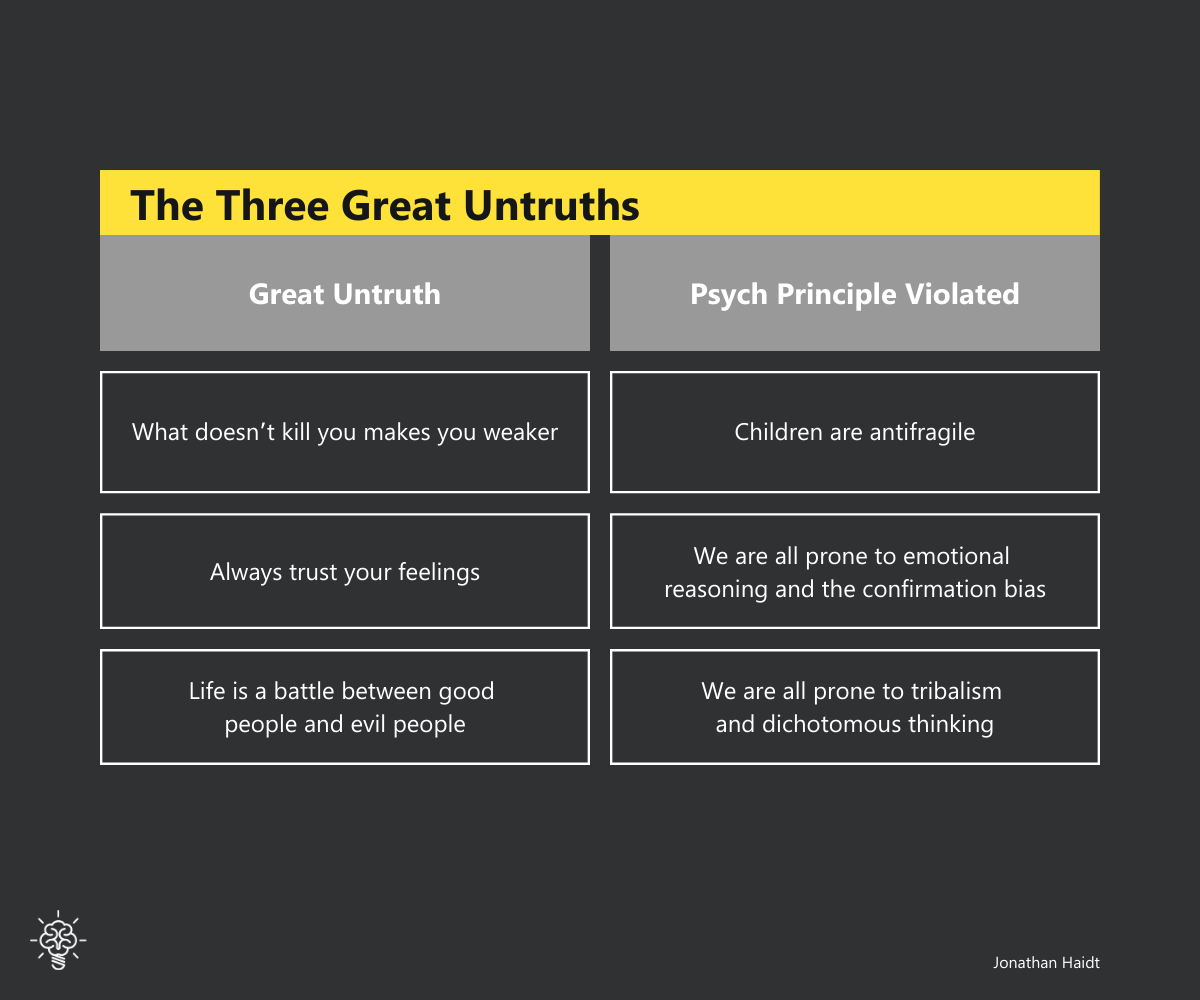

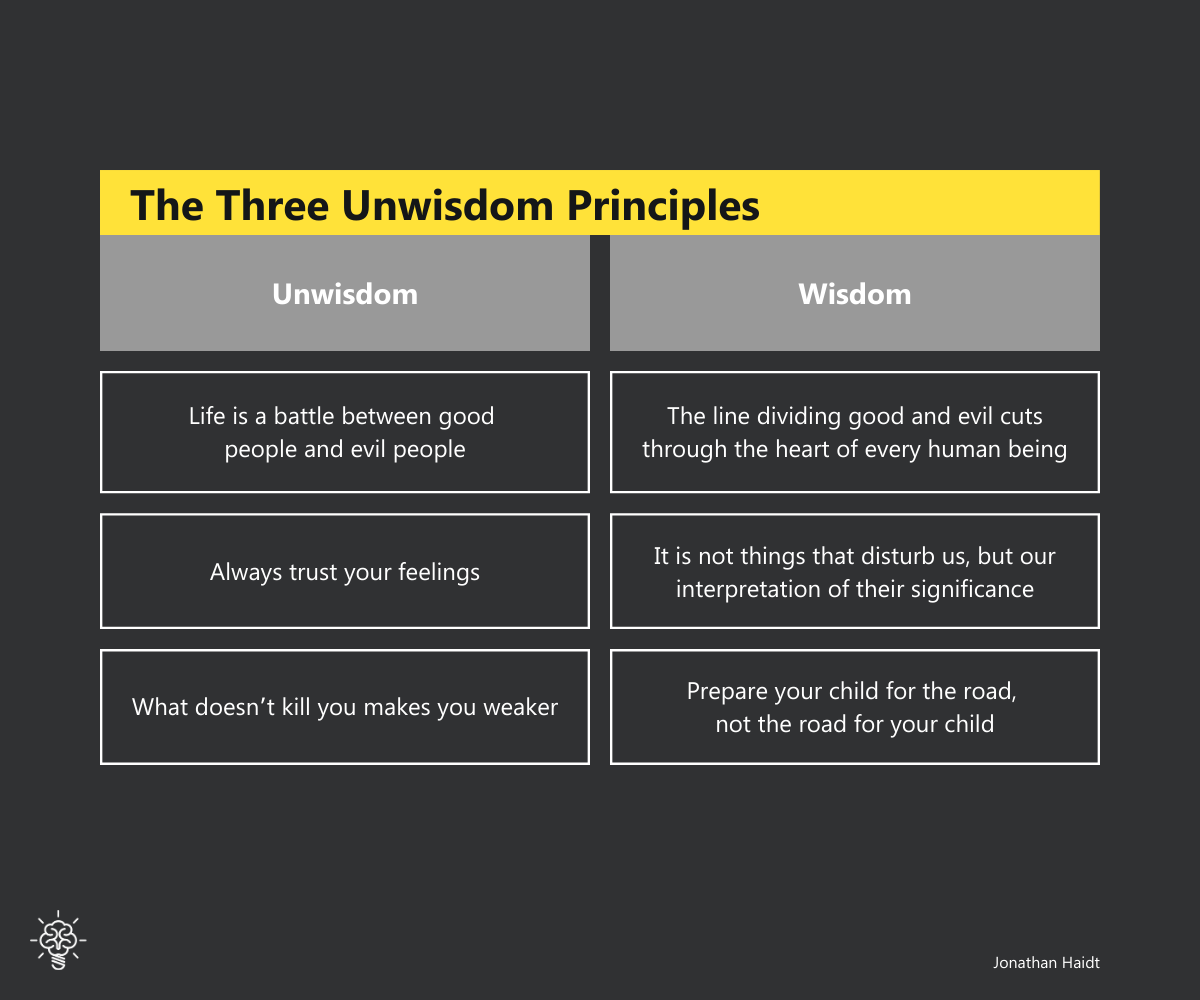

The book is based on analyzing three terrible terrible ideas. In addition to these social trends, what we see happening on campus is there are three really bad ideas.

Ideas, so bad, that if we can get students to believe them we can almost guarantee that they will be failures in life.

The Importance of Exposure to Challenges

Here are the three ideas.

I’ll just go through them one at a time that will be the rest of the talk. Bad idea number one is that what doesn’t kill you makes you weaker. I wrote a book, my first book is called The Happiness Hypothesis.

I read the wisdom literature of East and West and everywhere I could find. I pulled out the psychological claims and then I analyzed them are they true.

Every society that leaves us a wisdom literature has some insights about adversity and it is often stated like this, “What doesn’t kill me makes me stronger.” That’s the wisdom principle.

It’s the opposite of the great and truth.

Here’s why it’s true.

The most important word I can give you tonight is anti-fragile.

If you understand this word, you’ll understand everything else about the talk. You’ll understand that’s why the common things we do on campus in the last few years are mostly backfiring.

Why they’re often very badly considered.

The word comes from Nassim Taleb. He’s the guy who wrote The Black Swan.

He observed that there are certain systems that need to be tested and challenged. He’s one of the few people who correctly predicted the financial collapse in 2008, because he could see that the financial system was fragile. It had never been properly tested.

If anything goes wrong, it’s all going down, and he was right.

Afterwards, he’s thinking about this property of systems that get stronger when you test them and challenge them.

He says, “There’s no word in English for this.” He says, “We have the word fragile. If something is fragile, then you have to protect it.” If you have a wineglass and you drop it, it will break, and nothing good happens from that.

We give our kids plastic cups like sippy cups because if they throw them on the ground, they don’t break. Plastic is resilient.

Does the sippy cup get better from being thrown on the ground? Does it age well? No, it doesn’t do anything, it just doesn’t deform.

Taleb says we need more than that. It’s not just resilience. We need a word for things that get better when you throw them on the floor. He coins this term, anti-fragile.

Here are the great examples. Our bones are anti-fragile. If you take it easy on them, if you lie in bed for months, they will get thinner and weaker. If you bang them around, they get stronger because that’s the way bones are, they get stronger in proportion to the need.

The immune system is the best example. Let me go into that.

Peanut allergies have tripled, they tripled between the 90s and about 2010.

Why?

They only went up in countries that tell pregnant women to avoid peanuts.

Some immunologist got together do a study in which they tested the hypothesis that if you expose infants to peanuts, it allows the immune system to actually develop. You have to shock it, expose it, challenge it, and then it gets stronger. There’s an Israeli snack food called Bamba, which it’s puffed corn with peanut dust on it and kids love it.

They recruited 640 women who had recently given birth and whose infants were at high risk of peanut allergy because there was some other immune issue.

Here’s what they did.

They said, “Okay, half of you. Standard advice. Mom, don’t have any peanut products while you’re lactating. You don’t want to pass the peanut proteins to your child. Standard advice: keep your kid for your peanuts.”

Then, at the age of five, they tested everybody with a full immunological essay to see if their immune system responds to peanut proteins to peanuts. 17% of these kids had a peanut allergy following the standard advice: they’ll have to carry an EpiPen with them for life, and they have to always worry about food because it could kill them.

The other half were given Bamba and told, “Here, give your kid this snack food.”

I mean, I should read the article carefully. I’m sure they monitored it; they didn’t just say to go home and tell us if he survives.

They watch for signs, but what happened when they tested at age five? Here’s what they found: 3%. Only 3%. So, we could essentially eliminate peanut allergy in this country if we gave kids peanuts rather than running away from them.

As the author says, “Our findings suggest that the standard advice was incorrect and may have contributed to the rise in peanut allergies.”

This is an example of our subtitle, how good intentions and bad ideas are setting up a generation for failure.

Okay, let’s run the experiment again.

Only this time, we’ll use the whole kid.

All right, kids are fragile.

Protect your children.

You don’t want them getting hurt. Nothing good can happen if your kid gets hurt, right? You got to be there for them. You’ve always got to be there for them because you don’t ever want to let them go.

What if they get hit by a car? You can’t let the kid out. You have to be there for the kid. If you do that, you have to always be there for the kid. I work in a business school, and only recently are we hearing from business people who say, “I didn’t hire this person, and his mother called me.” It never stops.

It never stops.

When you get on the helicopter parent, whatever, escalator, whatever it is. It never stops.

Here’s the way to see how quickly this changed. I have a question for all of you in the audience. At what age were you let out? At what age could you walk out the front door, no adult with you, “Bye Mom, I’m going to Billy’s house.” Or you walk six blocks, and you and Billy go down to the store and buy some candy or whatever. Maybe you don’t want to do that, but that’s too dangerous.

The point is, at what age could you go out without any adult supervision? If it was first grade, you should say six. If it wasn’t until 11th grade, you should say 16.

Please, everybody, think to yourself, what’s your number? When were you let out without adult supervision, not just walking to school, more than walking to school?

Okay, now what I’m going to do is I’m going to ask you to call out your answer.

First, I only want people born before 1982. Raise your hand if you are born before 1982. Okay, so you’re all Gen X, Baby Boomers, and a couple of the greatest generation. Just you, only if you raise your hand. I’m going to sweep my finger around the room, and when I point to your section, just yell it out loud, okay? What’s your number?

Okay, so that’s what I always find. Six is always the mode.

This is what we always did, always did. Kindergartners are a little young, but first grade, that’s when kids go out.

You go out and play, come back at dinner. There are other kids out there. That’s what we always did. First grade, okay? Some kids said — many of you said eight, so between first to third grade. By third grade, everyone’s out.

Okay, now I’m going to skip the millennials. I’m sorry, but you’re not interesting because you’re just transitional. Now, just Gen Z. That is, and that’s most of you, students, here. This is what I always find; for older people, that’s what it is. Now, only if you’re born in 1995 or later, raise your hand high.

Okay, only you people, as I — wait, and only if you were raised in the United States, other countries aren’t as crazy as us.

Only if you were born in 1995 or later and raised in the United States, should you answer, okay? What’s your number? Okay.

Where’s your mom? Okay, so this is what I always find. All right, so the norm changed in the 1990s, beginning in the late 1980s. Just as the crime rate was ending, we had a huge crime wave from the 1960s to the 1990s.

Just as crime was plummeting and it became safe to let kids out again we changed our minds and said, “Oh, if I ever take my eyes off you, you will be abducted, therefore, you cannot go out. You can go to soccer practice because I will drop you off and then another adult is responsible for you until I pick you up, but we will not let you out of adult sight until you are 12.”

That’s the new norm that we developed in this country in the 1990s.

Many of us have idyllic memories of childhood or at least we see stories about it.

Then, in the 90s, we said, “No more of this. No more of this.”

What’s the result? Peter Gray is an amazing psychologist at Boston College who has done research on the effects of play. We learned so much from play. All mammals play; there is a biological imperative for mammals to play.

In play, we learn how to coordinate, how to be empathetic, how to make up rules, how to enforce rules, how to be flexible with rules, what do you do when you don’t get your way, we learn almost all of our social skills in play. It’s the richest source of learning for children.

We learn how to climb trees by climbing trees, not by taking a class on tree climbing where they show you PowerPoints.

What’s the effect if we suddenly take play away from children?

We say no more unsupervised play; everything is done by adults. What’s the effect? There is a big rise in psychopathology. One of the main things we learn in play is how to handle risk for ourselves.

If you’ve noticed what kids do is when they play with something like if they get a skateboard or anything, they play with it. Once they master it, they ramp it up, they make it harder. Once you can skateboard, you then skateboard down staircases, right?

Kids are seeking out the level of risk that their brain needs to unfold.

We have to learn to face risk in order to become self-governing adults.

In the 90s, we said no more, no more of that. You just sit there on your — Well, not on your device in the 90s. You just sit there and don’t go out where I can’t see you. As Alison Gopnik, a developmental psychologist, put it, “Trying to eliminate all such risks from children’s lives might be dangerous.”

There may be a psychological analog to the hygiene hypothesis, which is like what I was telling you about with peanut allergies. In the same way, by shielding children from every possible risk, we may lead them to react with exaggerated fear to situations that aren’t risky at all, such as a speaker coming to campus who’s saying things that you hate. We may isolate them from the adult skills that they will one day have to master.

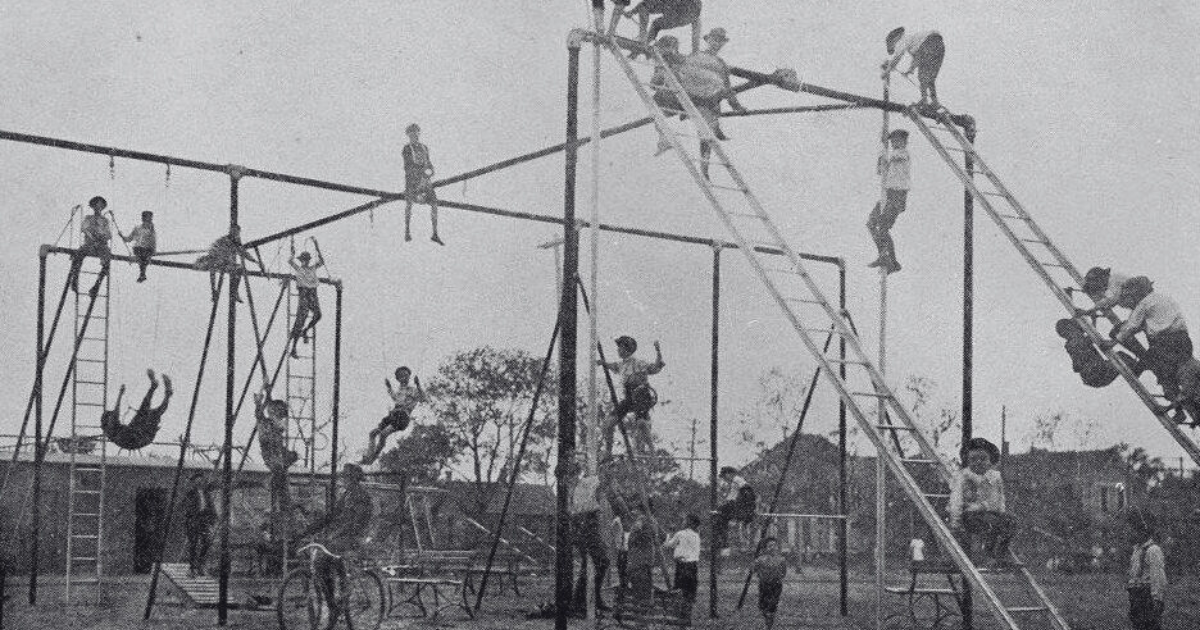

In other words, there is good reason to think that by protecting our children, we damage them, we harmed them, we interfered with their development. I’m not saying we need to go back to this, okay?

Image credit: BrighterSchooling

This is too much because kids could actually die.

There’s research on this. Death does not make you stronger, so that’s too much, but this is just right because on this playground, you can get hurt, and that’s very important because if you let kids face situations where they can get hurt, that’s the only way they can learn how not to get hurt.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Conversely, if you said, “No, let’s give kids a playground like this. This is what my kids were raised on.”

This is what most of you — Raise your hand if you recognize this from your childhood. This is boring. It’s very hard to get hurt here, and therefore, there’s not much you can learn. It’s fine for three-year-olds but not for eight-year-olds. The basic dictum, the basic insight that every culture knows, and it’s common sense once you see it, is to prepare the child for the road, not the road for the child, because you can’t fix every road that they will ever be on.

They have to learn how to go off-road or to rough roads.

In Britain, they’re ahead of us on this. They have all the same problems, not quite as severely, but their heads of schools are beginning to understand the psychology here. Kids need risk, and so they’re beginning to put construction materials out in a playground and physics professors here, look what this kid is going to learn. He’s created a lever. He’s going to basically discover Archimedes for himself. If the bricks go up like that, it’s a lesson he will never forget unless he has amnesia.

What do we do in America? The opposite.

In America, we say, “If anyone gets hurt, we will ban it for everyone, everywhere for all time,” and before we know it, everything is banned.

I just found this meme floating around. We are all balloons filled with feelings in a world full of pins. This would be a terrible thing to teach teenagers or children of any sort.

This, I think, is one of the reasons we end up with this. Talib has this wonderful insight in his book. He notes that, a candle is easily blown out. A candle flame is fragile. If you have a candle flame, you have to protect it with a glass sleeve, because any puff of wind will extinguish it. Once it reaches the stage of a roaring fire, the more wind, the better. The more wind the stronger it gets. What Talib says is, “You want to be the fire and wish for the wind.”

If you get that, you understand anti-fragility.

All right.

Bad idea number two. I’ll go through this one more quickly. Always trust your feelings.

In The Happiness Hypothesis, there was a whole chapter on changing your mind. This is the number one truth of pop psychology, this is the number one truth you find in every culture that leaves us any psychological wisdom literature.

The Stoics, the Buddhists, the Hindus were all fantastic on this.

They all said roughly the same thing. It is not things that disturb us, but our interpretation of their significance.

Buddha put it this way, “Your worst enemy cannot harm you as much as your own thoughts unguarded. Once you master your thoughts, then no one can help you as much. Not even your father or your mother. You learn to interpret the world in ways that are helpful for you, and then you can face just about anything.”

This is also the core inside of cognitive behavioral therapy, one of the most powerful and easy-to-learn techniques in all of psychology.

Aaron Beck discovered that if he could get depressed people to question their thinking patterns, they could be released from their depression temporarily. It would come back, but once they got practiced at it, they could actually keep it away forever.

In CBT, you learn to recognize a bunch of common thought patterns and cognitive distortions, such as negative filtering.

You only notice the bad stuff, overgeneralizing dichotomous thinking, breaking things into good and bad, black and white, right or wrong. Everything’s binary, and emotional reasoning.

Misinterpretations and the Role of Intent in Social Interactions

All of these distortions are encouraged on some campuses when we teach students, when we encourage emotional reasoning and when we teach them about micro-aggressions.

Let me explain.

The micro-aggression concept is a very widespread concept. It gets two things right, I think, but it gets two things wrong. Very wrong.

This is from an article. It goes back to, what’s the name? Goes back to in the 1970s, but it was popularized by Derald Wing Sue in a 2007 article, American Psychologist.

It is useful to have a word for small acts of aggression, in micro-aggression. These are in the context of racial insensitivity originally. It would be useful to have a word for somebody who tells a joke that seems insulting, but the guy says, “It’s just a joke. Come on it’s just a joke.”

Plausible deniability.

It would be useful to have a term for small acts of aggression.

As we’ve made progress from big overt blatant acts of racism, which are much lower. As we’ve made such progress, maybe things are in a small veil-deniable way. We’re great to have a term for that: micro-aggression. That would be great.

What about if it’s clumsy acts that make others uncomfortable, but there’s no aggression whatsoever? In fact, maybe the person was even trying to be helpful.

What should we call those?

Well, we don’t really have a word in the English language for that, but it would be great to have one — so great that we actually borrowed the French word, a faux pas, a false step, a clumsy act. It would be great. Especially as we try to increase diversity and inclusion, it’d be great to have fewer faux pas to teach people, especially if you have a lot of international students and students from across social classes.

They can’t know all the niceties of our language, around diversity issues. There’s a lot of faux pas. If we were to distinguish micro-aggressions from faux pas, that would be very helpful.

That would be great to talk to freshmen about, to help them get along with each other, and not give unneeded offense. That would be great. The problem is that, the things we’re talking about here, most of them, are not clearly acts of aggression. It’s things like asking someone, “Where are you from?”

If you look Asian, or if you’re looking some way not clearly white or black, people will often ask you, “Where are you from?” Then you say, “As my wife says, I’m from State College.”

Then they say, “Where are you really from, or where were you born? Where’s your family from?”

Now, is that an act of aggression? It’s often motivated by curiosity. People want to know.

Like, “I’ve been to Korea. I was wondering if you are Korean or Chinese.”

It’s generally not motivated by any hostility or aggression, but if you’re asked this every day, yes, that can be tiresome. This is what the micro-aggression concept gets right, that we need a term for that.

When we call it aggression, what happens? What does it do to people, what does it do to members of historically marginalized groups when so many daily interactions are now labeled for them, interpreted for them as acts of aggression against you.

Saying you speak English very well, or if someone mispronounces your name repeatedly, or if someone says there’s only one race, the human race, or if someone says, “America is a melting pot.”

Do we want students to interpret these as acts of aggression directed against them? Do we want them to see a world full of pins? That’s what happens when we call it microaggression.

If we call them faux pas, it would be great, but it gets worse, because the micro-aggression concept is presented always hands-to-hand with the idea that intentions don’t matter.

I don’t care that you weren’t badly intentioned. That doesn’t matter. All that matters is what someone felt.

In the end, what does the intent of our action really matter? If our actions have the impact of furthering the marginalization or oppression of those around us. One of the most basic aspects of morality is, we judge people by their intent.

If someone bumps into me, it makes a world of difference if it was intentional or accidental. It’s madness to ignore intent, but this is what we tell students, “Ignore intent. All that matters is how you feel, and you should be offended.”

Think about the challenge we face.

Every school I go to, every institution, every business, is trying to increase diversity.

If you increase diversity, that guarantees more faux pas and more misunderstandings. It has to happen. There’s no way around that. As long as you’re increasing diversity of more misunderstandings, there are two ways to handle it.

One, let’s talk about these issues.

Diversity is hard. It has many benefits, but if we don’t handle it right, it has many costs. It’s hard. Let’s all try to be more polite, but let’s also give each other the benefit of the doubt.

This is hard stuff, there are misunderstandings, we’re all flawed, we all have bad days, we have to be forgiving, we have to give each other the benefit of the doubt.

That’s one way to handle it.

I don’t know how it’s done, but imagine that’s the way it’s done at Penn State.

Conversely, imagine that instead of that, we teach students to focus only on the emotional impact. Ignore the intent, only focus on how you feel, and we are training you to detect more and more acts of aggression against you so that you will feel more and more marginalized, and then also along the way we’re going to give you a reporting system.

This is what we have at NYU.

You have one here at Penn State, too.

If you feel offended by something, there’s a number you can call. In every bathroom at NYU, there’s a number telling students how to report. If I say something that they don’t like, I can be reported. I don’t say things they don’t like. I can be much more offensive here at Penn State because you can’t report me.

That’s the second bad, bad idea.

Well-intentioned but if you make this the norm of your group before you know it you have increased tensions, hostilities and feelings of marginalization.

Third bad idea. Life is a battle between good people and evil people. It’s a whole chapter in The Happiness Hypothesis on the faults of others because we’re all self-righteous hypocrites.

We all are prone to dichotomous thinking and tribalism.

As Solzhenitsyn says in The Gulag Archipelago the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.

The ancients know this. The ancients knew this. Every culture advises us.

I don’t know of anyone where we were advised judge more and more harshly lest you beat before someone judges you. That’s not the way it works.

It’s always something more like why do you see the speck in your neighbor’s eye but do not notice the log in your own eye.

You hypocrite.

We’re hypocrites by design.

I cover that in the righteous mind. Why we were designed for hypocrisy, now, throw in tribalism. The Bedouin proverb, me against my brother. Me and my brother against our cousin. Me, and my brother, and cousin against the stranger.

This is tribalism. This is sports. This is politics. This is religion at times where tribal species and we bond with whatever group is needed to confront whatever the threat is.

It’s great fun, as you know, at Penn State every Sunday in the fall.

If you put these together, here’s what you get.

Here’s a really bad mix of it. You get a call-out culture. Let me just give you a quote on that, and then I’ll ask all the students whether you have it here. This is at Smith. Again, at elite schools in the Northeast, it’s really intense. It’s everywhere that I go, at elite schools, in New England especially, and also in California. Well, I will see what people say here.

A student at Smith wrote, “During my first days at Smith, I witnessed countless conversations that consisted of one person telling the other that their opinion was wrong. The word offensive was almost always included. People could soon detect the politically incorrect view and called the person out on their mistake. I began to voice my opinion less often to avoid being berated and judged by a community that claims to represent the free expression of ideas. I learned along with every other student to walk on eggshells for fear that I may say something offensive. That is the social norm here.”

This is what a Smith student said.

At many schools I go to, I ask, and 100% of the students will say yes. I was just at a fancy prep school in Connecticut, and 100% said yes, they have it. I don’t know.

Let’s find out just current Penn State undergraduates. We’ll only do undergraduates. Would you say yes?

Now I know it’s not pervasive here. It’s not in most of your classes, for sure. My question is, do you have any classes where this is the case, where you are afraid to speak up because that will happen to you? Just Penn State students. Raise your hand if your answer is yes; you’ve seen that here.

Raise your hand high. Okay. A lot of you.

Raise your hand if you say no. You have not seen that here. Okay. Actually, about three or four to one, yes. You have it here. It’s a Penn State student.

The Power of Inclusive vs. Divisive Identity Politics

Raise your hand if you’d say it’s present in most of your classes. Raise your hand high. Okay. Only a few.

Raise your hand if no, it’s not present in most of your classes. Okay, that’s my sense here at Penn State.

It’s much better than at most top schools in the Northeast, but you still have it. It’s in some classes. It varies a lot by department. There are certain departments that tend to foster this. It’s not just you who are self-censoring. We professors are self-censoring like mad.

I don’t teach nearly as provocatively as I used to five years ago. We’re all, in a sense, walking on eggshells.

Now a big part of the reason I believe is the prevalence of the idea of intersectionality.

Let me just explain this very carefully because we’re in the middle of a big culture war, and a lot of people from the right who want to say, “Oh, identity, politics and intersectionality, and cultural Marxism this is destroying the university.”

I’m not one of those. I’m not on the right. I used to be on the left. Now I’m a non-partisan, and it’s been incredibly freeing to be a social scientist studying the stuff without feeling like you’re on a team that has to win.

Let me be very clear.

The core idea of intersectionality is absolutely right.

Kimberlé Crenshaw developed the term, and the basic idea is that identities don’t just add; they interact. To be a black woman in America is not the sum of being a black person and being a female person.

There are unique indignities, insults, oversights, problems that a black woman faces in America and that others, especially — that say — white men, wouldn’t even notice and until you have terms for it, you don’t notice it. She has a great TED Talk. I urge you to watch her TED Talk. There’s nothing I object to in a TED Talk.

It’s a very good talk and it’s an important idea. Okay?

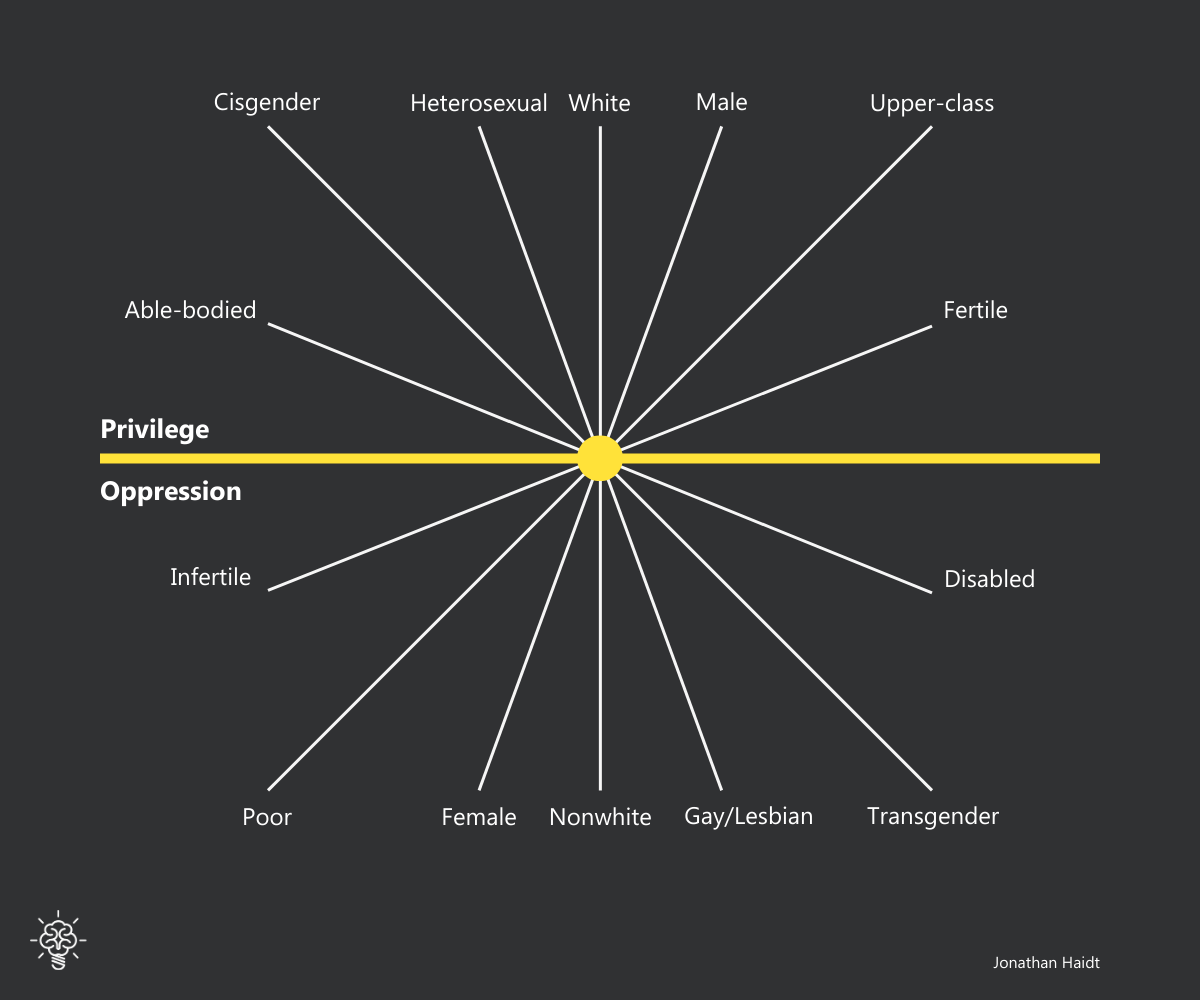

The problem, I believe, is that as it’s taught on campus, as it’s taught in certain departments that emphasize intersectionality, it’s taught with this basic intellectual structure. Let’s look at identities and they’re all binary.

You’re on one side or the other. You’re either white or you’re non-white. These are not just random dimensions. These are valenced. They are morally valenced. The ones above the horizontal line are privileged and powerful, therefore they are oppressors. Therefore they are morally bad.

Those are the bad people whereas the people below, the identities below, are the less, are the unprivileged. They are the oppressed and therefore they are the good people. They’re not just individual people. They’re intersectional addresses. The main intersectional address is the heterosexual white male. That is the person. That is the group. That is the cause of most of the problems. They are, whereas the people below, the identities below, are the less, the unprivileged. They are the oppressed and, therefore, really bad people. They are the oppressors.

Now, of course, there is such a thing as privilege. Of course, people have different experiences.

I’m not saying we shouldn’t be talking about these things but what I see coming out of people who take more than one course in these topics is a kind of an idea that the world is divided into good people and bad people.

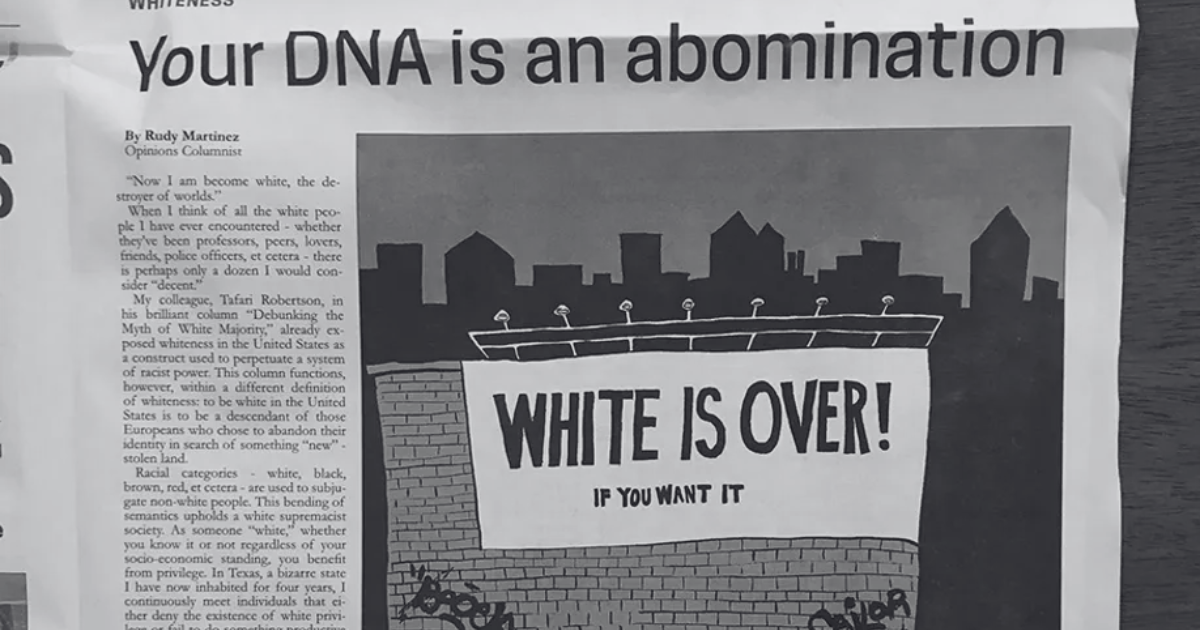

You can see it just in the last few years we’re seeing a lot of this. A lot of stuff that is really violent in a sense, or at least advocating violence in ways that would have been unthinkable 10 or 20 years ago.

A student at Texas State University, ontologically speaking, white death will mean liberation for all. It goes on around about white genocide.

Common enemy identity politics at Texas State U, 2017 (Image Credit: FoxNews)

Now, he doesn’t literally mean that white people should be biologically killed. He means culturally killed.

White people should be wiped out in terms of their cultural presence, but to use this language of genocide in a student editorial — this is just not very helpful if you’re trying to create a tolerant multicultural environment. It’s not just students on campus.

Well, this is another one. This is at the new school a few blocks north of where I live. It’s an incredibly progressive, anti-racist school, but some students there have learned that the new school is a bastion of white supremacy, so they need special spaces for everyone who is not a straight white person.

It’s not just students. It’s now in the media. It’s now adults. It’s now journalists. Well, this is a gender studies professor.

Of course, Harvey Weinstein is a criminal. He’s a horrible man who deserves to go to jail.

We now know many women have been harassed and molested, and even raped that we didn’t know before.

The Me Too movement is very, very important.

How should we react to this? Well, one way would be to say the world is divided into good people, the women, and bad people, the men. We women have every right to hate you men as a sex, as a gender. You have done us wrong.

The New York Times recently hired someone who writes this way.

Sarah Jeong had a number of tweets about how much she hates white people, and The New York Times hired her.

Interestingly, the feminist named Jessica Valenti, defended her with an exact paraphrase of great untruth number three, as she put it, “Sarah Jeong is good. Her haters are bad.”

It’s not difficult. It’s that simple. Good, bad. That’s all there is to it.

Then, recently, we saw a really horrible one. Many people again. People who are in this intersectional culture that judges by race and gender saw this photo, and as Reza Aslan put it, “Honest question, have you ever seen a more punchable face than this kid?” Because violence against the bad people is a good thing.

They’re the cause of our problems. We should round them up and punch them or kill them.

Again, this is not the best way to think if you’re trying to create a tolerant, open, diverse, multicultural society or university. Here’s a much better way to think. It’s the way that the great civil rights leaders thought. It’s the way that works. It’s called common humanity identity politics. Identity politics is not a bad thing. You need politics. In fact, the motto of the McCourtney Institute is “partisans for democracy.”

Politics is a good thing.

Groups need to organize to address grievances and injustices.

You have to have identity politics.

If corn growers can organize and comic book readers can organize, then black people can organize, Jewish people, and gay people.

Identity politics is not bad, but if it’s organized by common hatred of the enemy, it gets ugly quickly, and it never works in a university. If you follow some of the great civil rights leaders, like Pauli Murray, who was gay, we will now say transgender, black, Episcopal priest who got a law degree at Yale.

She said, “I intend to destroy segregation by positive and embracing methods when my brother’s try to draw a circle to exclude me, I shall draw a larger circle to include them.”

This is really good social psychology. Draw a circle around us all, and then within this circle, we can talk about difficult things. The Dalai Lama is also fantastic, as Buddhists tend to be on this. “I’m Tibetan, I’m Buddhist, and I’m the Dalai Lama, but if I emphasize these differences, it sets me apart and raises barriers. What we need to do is pay more attention to the ways in which we are the same as other people.”

Imagine a university that was structured on the three unwisdom principles. Imagine what it would be like to be a student there. Imagine a business choosing where to hire from, what business in its right mind would hire someone who came out believing these three things.

Conversely, imagine a university that rejected them and that was based on the basic psychological principles that I’ve explained today. What can we do? What can Penn State do to set Gen Z up for success?

Recommendations for Universities: Fostering Resilience and Diversity

Briefly, point number one: you need viewpoint diversity.

You have to expose people to a variety of viewpoints.

As Ruth Simmons said, “Learning is the antithesis of comfort. The collision of views and ideologies is in the DNA of the academic enterprise.”

You have to expose students to ideas that they dislike and reject.

Point number two.

I co-founded this organization, Heterodox Academy, because I was alarmed as a social psychologist that everyone in my field was on one side politically and that made it hard for us to actually think clearly about problems.

Please raise your hand if you’re a professor or an administrator at Penn State.

Anyone who just raised their hand I invite you to join Heterodox Academy. Just go to heterodoxacademy.org, click on about us, click on join, and I welcome you.

We are the only politically balanced organization in the Academy. Equal numbers of people on the left and the right with 2,500 professors and now we’re at we have hundreds of administrators.

Third, use the open-mind program.

We designed it to be used in freshman orientation, but it works great in all kinds of classes, political science classes.

Walk students through why it’s good to talk to people who differ from you, how to cultivate intellectual humility, helps you break free from your moral matrix. I won’t go through this. We have data that it actually works, it does what it’s supposed to do. The good stuff goes up the bad stuff goes down.

A fourth point, teach all incoming students Cognitive Behavioral Therapy.

You could hire another therapist for $130,000 or you could buy the entire incoming class his book for $10 a piece.

It’s a lot cheaper and then students themselves could actually do therapy on themselves and it just teaches critical thinking skills. Last I’m going to end with a three-minute video. This basically sums it all up.

Van Jones, a Democratic activist. He was in the Obama White House. Van Jones gave a talk at the University of Chicago and they had just had an event on campus at Chicago where somebody from the Trump administration was going to speak and some students protested.

They wanted him disinvited. David Axelrod, Democratic strategist interviews Van Jones and says, “Van what do you think about this?” Just listen to the way-this is the most brilliant exposition of anti-fragility I have ever heard.

David: I have a different view, but I’m interested in yours.

Van: I don’t like bigots and bullies. I just want to point that I’m against bigots, I’m against bullies. Just leave that as it is.

David: Those who like bigots and bullies, raise your hands up.

Van: I’m going to say I got tough talk for my liberal colleagues on these campuses. They don’t tend to like it but they tend to like me so I get away with it. I’m going to keep trying —

David: That’s the proposition.

Van: Exactly. I want to push this. There are two ideas about safe spaces. One is a very good idea and one is a terrible idea. The idea of being physically safe on a campus, not being subjected to sexual harassment and physical abuse or something like that or being targeted specifically personally for some kind of hate speech. You are an n-word or whatever that I am perfectly fine with that. There’s another view that is now I think ascendant, which I think is just a horrible view which is that I need to be safe ideologically. I need to be safe emotionally, I just need to feel good all the time, and if someone says something that I don’t like that’s a problem for everybody else including the administration. That is a terrible idea for the following reason.

I don’t want you to be safe ideologically. I don’t want you to be safe emotionally. I want you to be strong. That’s different. I’m not going to pave the jungle for you. Put on some boots and learn how to deal with adversity. I’m not going to take all the weights out of the gym, that’s the whole point of the gym. This is the gym. You can’t live on a campus where people say stuff you don’t like and these people can’t fire you, they can’t arrest you, they can’t beat you up, they can just say stuff you don’t like and you get to say stuff back. This you cannot bear.

Jonathan: Okay. You get the point.

There are two models of adolescents and two models of young people that we can have, that we can encourage our students to think of.

They can either think of themselves as being balloons full of feelings in a world full of pins or they can think of themselves as fires. To close I would just like to say that every student here you are the fire now go find some wind. Thank you.

Watch the full video of Jonathan Haidt’s Penn State lecture here.

Future Quotes: Maintaining Optimism and Fostering Innovation

“I believe that children are our future. Unless we stop them now.”– Homer Simpson If popular culture indicates anything, it’s how dramatically our perception of the future has changed over…