Table of Contents

In 1959, during his very first meeting with a broken Green Bay Packers team (they were the worst team in the NFL at the time), the new coach, Vince Lombardi, stood before his players and said:

Gentlemen, we have a great deal of ground to cover. We’re going to do things a lot differently than they’ve been done here before. We’re going to relentlessly chase perfection, knowing full well we will not catch it, because perfection is not attainable. But we are going to relentlessly chase it because, in the process, we will catch excellence.

Under Lombardi, the Green Bay Packers won five NFL championships in the next seven years. Lombardi became one of the most legendary coaches in American football history.

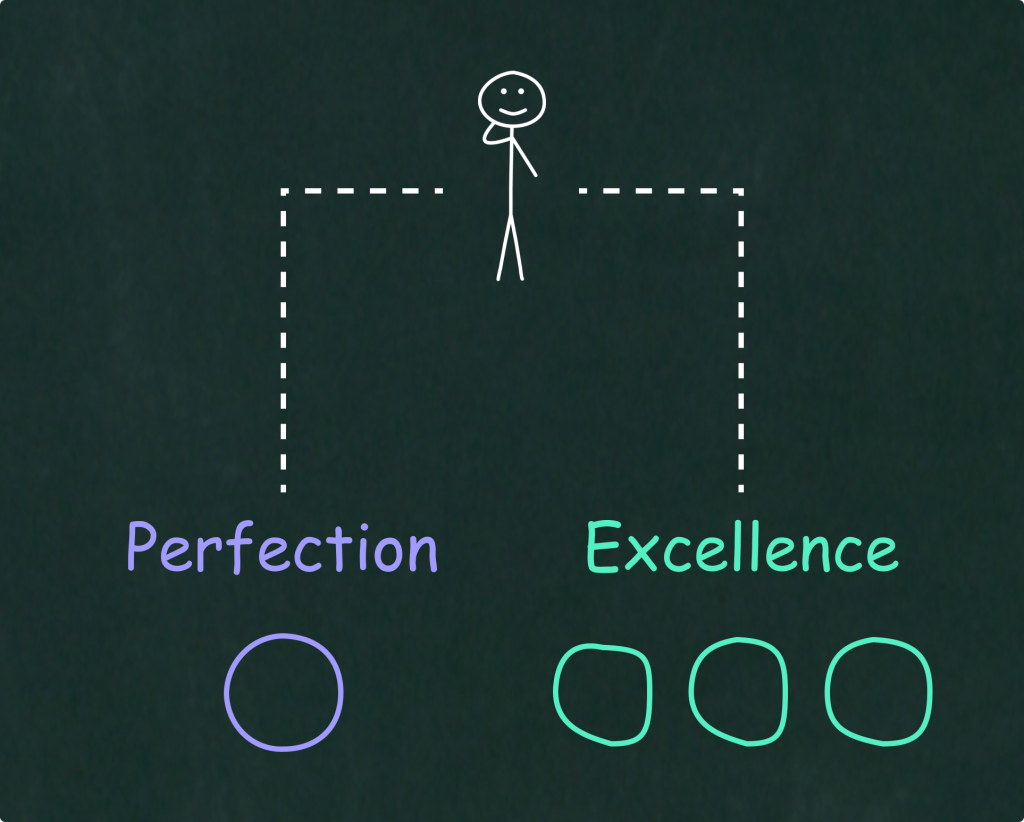

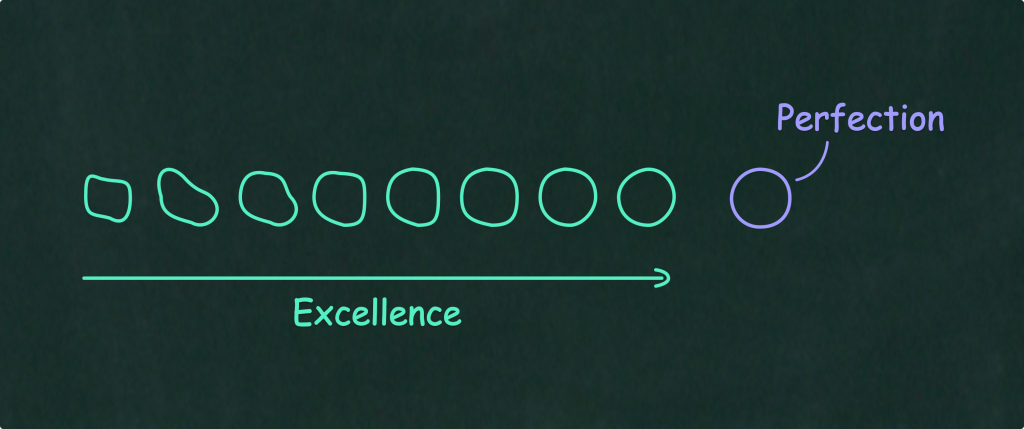

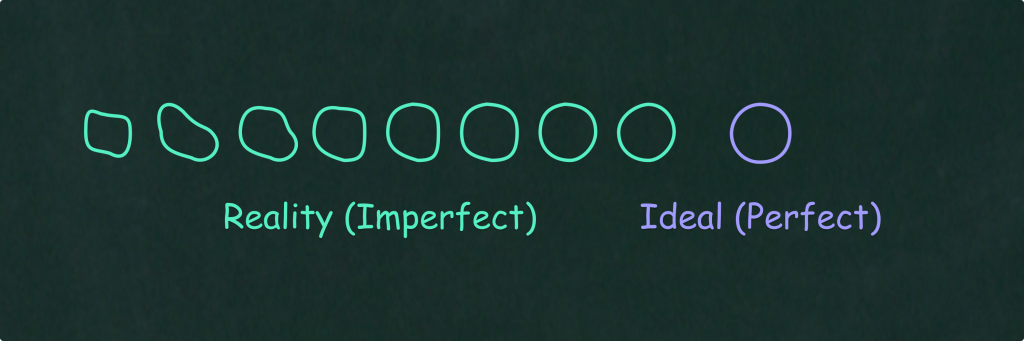

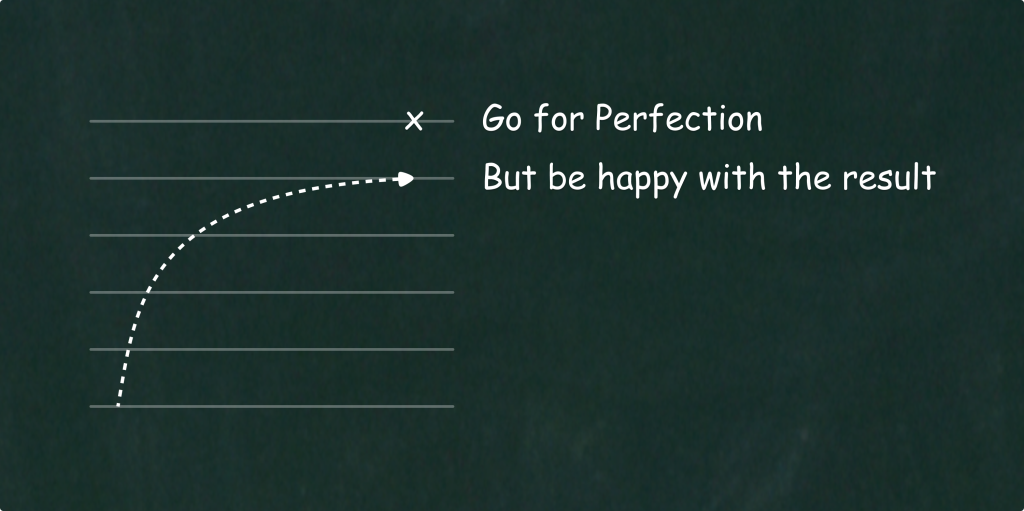

From this story, we can already see the difference—and the relationship—between perfectionism and excellence. Perfectionism, at least the healthy version (we’ll see later that there’s also a negative version, which is actually counterproductive), is an ideal that should guide our actions. But it is only an ideal—it’s not something you can truly attain, because reality is imperfect and there’s always room for improvement.

The point of being guided by perfection is not to actually achieve it, but to become excellent in the process.

You will never be perfect, but you can always be better.

– Warren Buffet

[From his last letter to shareholders as CEO of Berkshire Hathaway]

Never Stop Becoming

A great piece of wisdom I got from Brian Chesky, the co-founder of Airbnb, is to be in a constant state of becoming. Never to tell yourself: “I’ve made it.” Because once you’ve “made it,” you’re done; there’s no more learning or growing — no more pursuit of perfection, no more becoming excellent.

And if you take perfection as your north star, you’ll naturally be on a constant journey of becoming, because you can never truly reach perfection. Here’s the quote from Brian Chesky:

I was with Sam Altman probably a few weeks ago at dinner, and I told him:

“I still feel like I have a lot to prove. I haven’t made it yet.”

And he was really surprised. He’s like, “What are you talking about?” And I didn’t even realize that he thought that was an absurd notion, but I said “No, I haven’t made it yet.”

It’s not to say I’m not grateful, or I feel like I need to get somewhere — so that then I’ll feel worthy. But I still have this kind of beginner’s mindset — the bigger I get, the more a beginner I tend to feel. It’s like a weird feeling.

I think that when I first took off [had success with Airbnb], I thought maybe I can do everything or I knew more than I certainly did. But the moment you get to some frontier of knowledge, you start to become a beginner again! And everything is new.

And so I think the first thing I try to do is to be a beginner.

Pablo Picasso had a saying, he said “It took me four years to learn to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to learn to paint like a child.”

And so I’ve tried to always see the world through the eyes of a child. And I think one of the key characteristics of a child is curiosity, to see everything with fresh eyes, to not have too many judgments.

[For instance] When I was trying to figure out how to run a company…

- I studied the history of Divisional Organization,

- I studied Steve Jobs,

- I studied Bill Gates,

- I studied Alfred Sloan (at General Motors, and from whom MIT Sloan is named after),

- Also, the founding of Divisional Companies (founded by DuPont)…

So, I try to understand the sources of things.

I try to learn…

So, I think that that is the key. It’s learning, it’s growing, it’s curiosity, it’s constantly having that hunger and that fire to always want to be better, to feel like “I haven’t made it yet.”

The reason I say “I haven’t made it yet” is because if I’ve made it, then I’m done.

And I want to feel like an artist. Bob Dylan used to say “an artist has to be in a constant place of becoming.” And so long as they don’t become something, then they’re gonna be okay.

And I hope [that] years from now, Lenny, I hope 70% of what I said I still believe, but if 100% of what I say I still believe then I probably haven’t learned very much. And so, if 90% I say I don’t believe anymore then I’m delusional and wrong. But I sincerely hope that I retract or change or modify a few things I said today in a few years, because that will mean that I’ve gained more wisdom. And so how do I do that? By being curious.

Strive for Perfection to Become Excellent

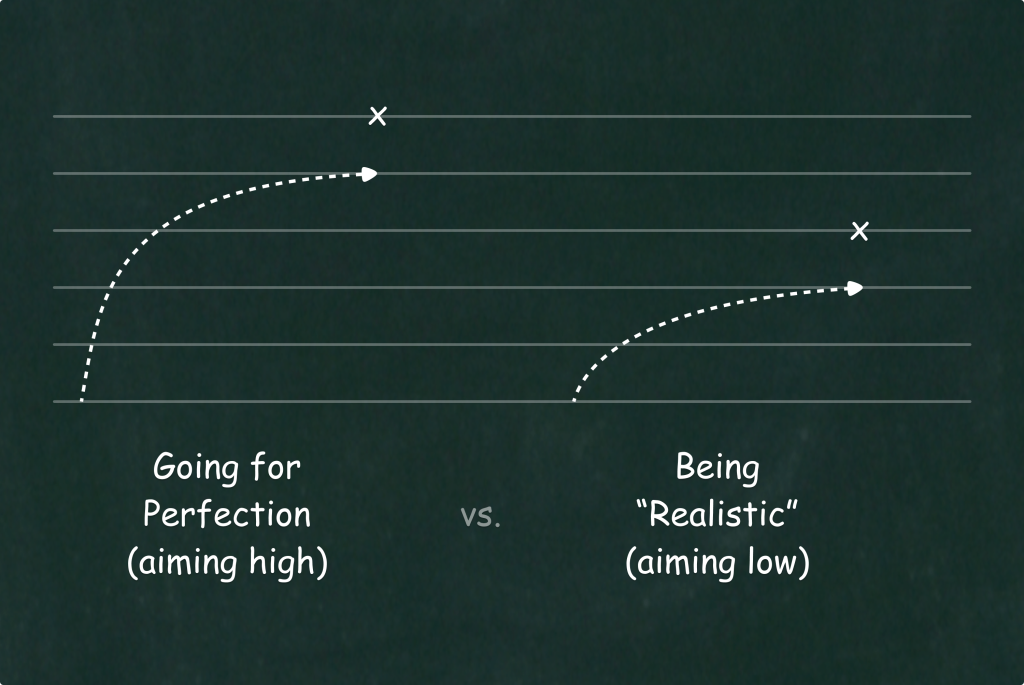

The acclaimed actor Matthew McConaughey also says that you should strive for perfection, because it will make your work far better than if you aimed for something less than perfect. At the same time, you must remain aware that perfection is only an ideal—something you can never actually achieve—because reality itself is imperfect.

But my hunch — I want to see what you think about this theory — is:

Shooting for an A and making a C, it’s better than shooting for a C and making an F.

So, go for perfection. Reality always comes in under it. But in that moment when you see the inevitable reality, the outcome, the result, how quickly can we go “Okay, I got so much more out of it — the job, the person, myself — because I went for perfection, than if I’d have just gone for just pass class.”

But what can be hard for me sometimes is… it can take me too long to come down from when “Oh, it didn’t hit perfection”, and maybe it takes me a week to go: “Dude, now do you finally realize that of course you weren’t going to get perfection, but you got so much more out of it because you went for perfection!”

So, be pleased with reality because you got a good grade on it, man. That work was good!

I say this all the time (and I never mean this in a disrespectful way): I’ve never done a movie or a performance that lived up to what I thought it could be. Because I’m thinking it can be divine. Comes out maybe majorly inspiring, may speak to masses, even have some magic to it, but not divine.

– Matthew McConaughey

[Video Source]

When Perfectionism Turns Negative

When you start viewing perfection as something actually attainable, that’s where the problems begin. Expecting true perfection is wishful thinking, because you can’t expect perfection in an imperfect world. This kind of wishful thinking clouds your ability to see reality as it is—and causes you suffering again and again when you inevitably fall short.

Eventually, you’ll likely become demoralized and give up on whatever project you’re working on, because you’ll run from disappointment to disappointment, never reaching your idea of perfection.

In his book How to Make a Few Billion Dollars, Brad Jacobs argues that perfectionism is a cognitive distortion — a mindset where anything less than perfect execution leads to intense frustration. But he says that if we accept that life is imperfect, we’ll make fewer self-defeating demands for perfection on ourselves and others.

“Not beating myself up” has been a hard-learned lesson for me and those around me. I became much happier in my middle age when I stopped expecting unrealistic levels of perfection from myself and my family, my friends, and my co-workers, not to mention customers, vendors, and shareholders.

– Brad Jacobs

[From his book – How to Make a Few Billion Dollars]

This is also one of the key insights from Dan Sullivan’s The Gap and The Gain : When you stand on a beach and look out at the horizon, you intuitively know it cannot be reached. It exists to orient you, not to be attained.

Perfectionism treats goals the opposite way. It mistakes an imagined horizon for a destination — something you’re supposed to arrive at — and then quietly punishes you for never getting there. Instead of using ideals to guide direction, it uses them as a measuring stick for inadequacy.

The Passive Person Problem

Another danger of perfectionism is that it can turn you into what John D. Rockefeller would call a “passive person.” A passive person is someone who waits until everything is perfect before taking action. But that’s not the right attitude. The right attitude is to make the best of the cards you’re dealt—to embrace life’s imperfection, and then pursue the ideal of perfection, knowing that you’ll never get there but will catch excellence along the way.

Here’s Rockefeller on the passive person (from the book The 38 Letters from J.D. Rockefeller to his son):

Many people make themselves into a passive person. They want to wait until all conditions are perfect, that is, when the time is right, before taking action. Life is an opportunity at any time, but there is almost nothing perfect. Those passive people have a mediocre life, precisely because they must wait for everything to be 100% profitable and perfectly safe before doing something.

This is a fool’s approach. We must compromise in life and believe that what is in hand is the opportunity we need now, so that we can keep ourselves out of the quagmire of waiting forever before falling into action. We pursue perfection, but there is no absolute perfection in life, only near perfection. If you wait until all conditions are perfect, you can only wait forever, and the opportunity will be given to others.

Those who must wait until everything has been prepared will never leave home. To become the kind of person who “will do it now,” you must stop daydreaming, and to always think of the present and start doing it now. Sentences such as “tomorrow,” “next week,” and “future” have the same meaning as “can never be done.” Everyone has a time when they lose confidence and doubts their abilities, especially in adversity. But people who really understand the art of action can overcome it with strong perseverance. They will tell themselves that everyone has failures, and when they fail miserably, they will tell themselves no matter how much preparation they have made and how long they think before they do it, will inevitably make mistakes. However, passive people do not regard failure as an opportunity for learning and growth, as they are always admonishing themselves: perhaps I really can’t do it, so that is why I have lost my eagerness to participate in future activities.

Radical Acceptance is the Antidote

In his book How to Make a Few Billion Dollars, Brad Jacobs offers a solution to counter this cognitive distortion of perfectionism: Radical Acceptance—a mindfulness practice that helps you embrace reality as it is.

Accepting your own imperfections is the gateway to an even more daring mindset: accepting the world as it is, not as you wish it would be. This is another fruit of my adventures in cognitive behavior therapy. About 20 years ago, my wife and I went to some workshops on mindfulness led by Marsha Linehan, whose techniques incorporate a core principle she calls radical acceptance. This boils down to being fully present in the moment and accepting reality. It requires that you let go of the illusion of control by acknowledging the facts as they are, even though you may want them to be different.

Radical acceptance has many practical applications in business. For the oil traders I trained, it was, “Block out how much you won or lost on your trade and focus on the best thing to do right now. If you think the market’s going up, buy more. If you think the market’s going down, sell—and make sure you can quantify the risk involved in each action. It’s that simple.”

Radical acceptance quiets the noise created by yesterday’s decisions and today’s wishful thinking. It allows you to make a logical, forward-looking decision based on what’s likely to happen next—that and risk management are the big, relevant considerations. Otherwise, you’re just gambling, and most gamblers lose.

Here’s a story about radically accepting a $500 million loss from when I ran United Rentals. It was the late 1990s, and my ears perked way up when Congress enacted TEA-21, the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century. In theory, this legislation was going to allocate about $600 billion to rebuild the nation’s infrastructure, beginning with roads, bridges, and tunnels. That’s a lot of money, even for the federal government.

Seeing such profuse funding up for grabs, I started scooping up big road-rental companies—the ones that provide barricades, cones, striping, and the like. Then I waited for the market to come to me, which in an ideal world would have happened in short order. But this was the real world, and only about a third of the allocated government funding was spent, and that was in dribs and drabs over time.

My decision turned out to be a huge mistake, and there was no point in compounding it. We ended up selling those road-rental companies at a half-a-billion-dollar loss because it was the best way forward under the circumstances.

As I mature, I look back on all the times I thought I had life figured out and realize I got some big things wrong. That’s growth.

The path to radical acceptance begins with non-judgmental concentration, which is part of mindfulness. With non-judgmental concentration, you’re fully present in the moment, putting all your attention on one thing to the exclusion of everything else.

You can direct awareness to your body, your mind, your emotions, or how you’re feeling. You can be aware of how your heart is beating, how you’re breathing in and out, the thoughts you’re having and how you’re reacting to those thoughts, or the emotions you’re experiencing as a result of those thoughts. Or your attention can be on the person you’re speaking with, the room, the group, or the business environment. Whatever it is, you’re focusing on that one thing alone.

Non-judgmental concentration is step one for me when a thorny issue arises—it’s how I put my mind in a good space, because it keeps me in the present and quickly lowers my stress level. I’m not brooding over what happened or worrying about what might happen. I’m not thinking about the past or the future or anything at all except what’s in my mental crosshairs.

When using this technique, it’s important to refrain from projecting bias onto the subject of your concentration. If you choose to focus your attention on a person, don’t rush to judge that person as being good or bad. In many ways, the concepts of good and bad are just tools that our self-centered minds use to sort through sensory data. For example, a controlled fire at a comfortable distance feels warm, so your brain thinks that’s good. An uncontrolled fire that’s burning your hand hurts, so that’s bad. It’s the effect the fire has on you that makes your brain think it’s good or bad, not the simple fact that it’s a fire.

Non-judgmental concentration trains your brain to realize that the people and things in your life don’t exist relative to you; they simply exist. If you can take yourself out of the equation, you’ll have a much clearer view. Uncluttered by judgmentalism, you can work more efficiently, because you won’t be as distracted, and you can think more objectively, too.

Final Thoughts

Perfectionism and excellence go hand-in-hand. When you strive for perfection, you catch excellence in the process.

But perfection should remain in the realm of ideas—it’s never something you can truly attain. If you make it your goal to actually achieve perfection, it becomes a fool’s errand. You’ll lose touch with reality and eventually grow demoralized.

The most successful people live in a constant state of becoming. They understand that perfection is not a destination, but a direction — something to orient action, not measure worth. When ideals are held properly, they don’t crush motivation; they generate excellence.

If You Liked This Essay, Check Out These Sources

- Warren Buffet’s last letter to shareholders as CEO of Berkshire Hathaway

- Brian Chesky on the Lenny’s Podcast

- Matthew McConaughey on The Diary Of A CEO Podcast

- Pain vs. Suffering: The Seed Of Your Life Story

- How to Make a Few Billion Dollars, by Brad Jacobs

- The Gap and The Gain, by Dan Sullivan

- Mistakes vs. Regrets: How This Difference Can Transform Your Life

- The 38 Letters from J.D. Rockefeller to his son, by John D. Rockefeller