Table of Contents

It’s possible to learn a lot from unpacking “obvious” questions. For example: What precisely is the difference between propaganda and public relations?

The origins of public relations, like most of the great inventions of the 20th Century, has its roots in war.

Edward Bernays, the father of modern public relations notes that when he came back stateside, he realized that propaganda could be used for peace as well as for war. However, “propaganda” was associated with the Germans, so he needed a better term for it. Hence, in what was perhaps the first public relations makeover in history, propaganda, the bigger scary German beast, became transformed into public relations, the American business with the “can do” attitude.

Bernays was Sigmund Freud’s nephew, and while he might not have had Freud’s academic pedigree, he certainly had an understanding of how the human mind worked — the proof is in the pudding.

Bernays’ Propaganda Convinces Americans to Join World War I

His earliest work was for the world famous opera singer Caruso on his big American tour. Bernays’ successful promotion of this tour soon caught the eye of Washington and he was asked to help promote then-President Woodrow Wilson’s drive to war with Germany and the Central Powers during the Great War. Previously, America had been famous for its non-interventionism. Wilson wanted America to take a more active role in world politics, the beginnings of America as world police.

Unfortunately, there were two large immigrant groups in America who weren’t on board. The Germans, who loved Germany, and the Irish, who hated the British. Wilson needed to sell the war to a reluctant American public and he used, among other things, lies about why the Germans sunk the Lusitania. To that end, he employed Bernays to promote this vision, as Bernays recounted in 1991:

Then to my surprise they asked me to go with Woodrow Wilson to the peace conference. And at the age of 26 I was in Paris for the entire time of the peace conference that was held in the suburb of Paris where we worked to make the world safe for democracy. That was the big slogan.

“Make the world safe for democracy” is the key term here and it worked in as much as Wilson got the Europeans powers to agree to Wilson’s terms, at least in theory.

Bernays was astonished by the reception of Wilson in the United States after the war. He was seen as a liberator and a great man who would recreate the world on the basis of individual freedom.

Crowds surged around him just trying to get a glimpse of the man in the flesh. It was here that Bernays began wondering if he could do in peacetime what he had done for Wilson during the war.

This is where modern public relations was born. But it wasn’t long until the state figured out that they could use this new industry to sell another war.

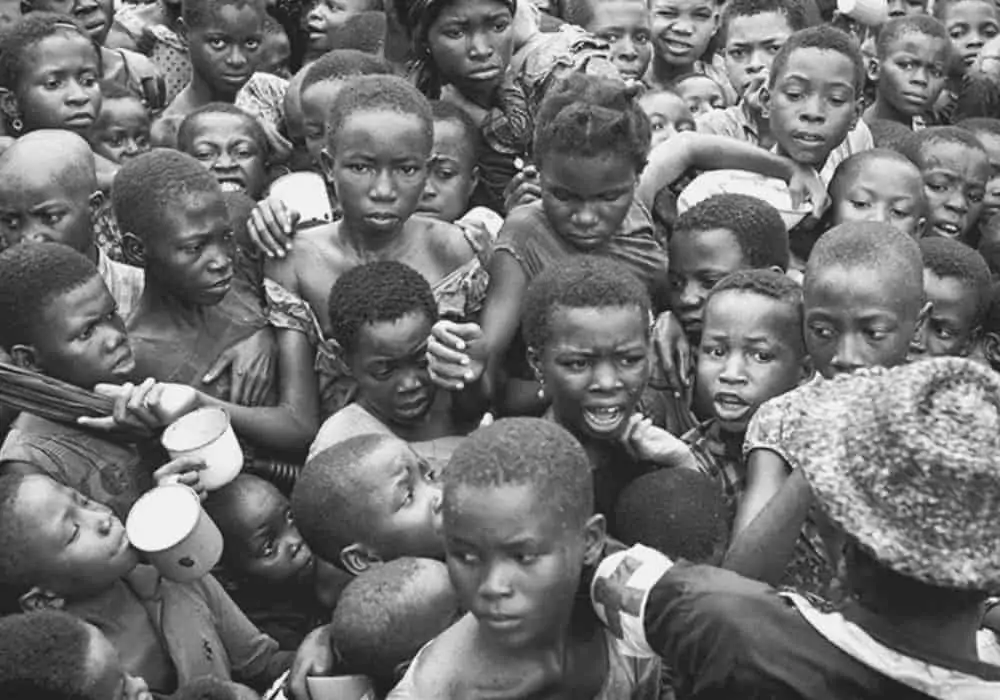

Public Relations Turns the Biafran War Into a Moral Crusade

The first modern “humanitarian intervention” was during the Biafran War, which began in 1968. For those unfamiliar, the Eastern section of Nigeria declared independence under the name of Biafra. The Nigerian government predictably attacked and the Biafrans had a bad time — but no one in the West cared. In fact, the British government was having a great time selling weapons to the Nigerians.

The Biafrans responded by hiring MarkPress, a PR firm based in Geneva. They wanted MarkPress to sell the Biafran side of the story to Europeans. MarkPress helped the Biafrans give their war a personal touch that connected emotionally with Europeans. They framed the war as a moral one with an evil regime in Lagos cynically aided by a corrupt political class in London. The Biafrans, for their part, were innocent victims, starving to death because of a war that wasn’t their fault.

British newspapers ate it up. The Biafrans quickly became a cause celebre among cultural elites, culminating in a 48-hour fast in support of Biafrans in Piccadilly Circus over Christmas. The war no one knew or cared about became the Good War. The Biafrans were now, in the eyes of the British public, justified in resisting the evil regime in Lagos. It was part of a universal struggle of the downtrodden and the innocent against belligerence and tyranny. However, this view quickly grew completely out of the control of the PR firm which crafted it.

The image of the starving child originated during this time and, as of 2020, hasn’t gone away. Anyone wanting to start a war anywhere needs to do little more than find (or create) a picture of a sad, sick, scared, and starving child that they can use for their own purposes.

In the case of the Biafran War, the effects are difficult to quantify, but they are clear to see: A war that might have ended very briefly dragged on for two and a half years. Hundreds of thousands died. While aid agencies and longstanding Biafran partisans in the West deny this, rebel Biafran leader Colonel Ojukwu is on record as saying that the money he got from aid agencies went not toward feeding the destitute, but towards the weapons needed to continue the war effort. This is rooted in a trick that Bernays learned early on: Any private interest can be advanced by turning it into a public cause, a moral crusade.

So what precisely is the difference between propaganda and public relations? It might be said simply that public relations is the freelance, private-sector version of propaganda – a distinction without much of a difference. And in the case of the Biafran War, the effects were tangible: People died.

It might be easy to become too cynical with regard to public relations and its role in crafting public policy. We might begin to see a hidden agenda lurking behind every moral crusade. But is that necessarily a bad thing? One need not see the Nigerian government as righteous or the Biafran rebels as cynical anglers to see that the involvement of the British public had a net-negative effect.

It’s a powerful lesson, one that we should remember the next time we find our emotions being manipulated for the downtrodden. Who benefits, and how, are always fair questions and ones that can act to inoculate us against making a bad situation worse.

Perception Management

One of the truest cliches in politics is that “perception is everything.” This is why the government seeks to manage public perception using perception management or impression management. Example: UFOs.…